The Global Crisis and its aftermath has focused attention on increasing inequality, and specifically on the declining real incomes of the working poor; at the same time, the role of education and acquired skills in upward mobility has also been well appreciated. The potential for job-related training as a means to achieve growth in incomes at the lower end of the distribution and reductions in inequality has also been noted (e.g. Attanasio et al., 2017). With limited resources, what should be the focus of public investment in secondary and tertiary education? Looking at the OECD countries, an observed pattern and a tentative answer is that improved access to better vocational education can probably contribute more than large increases in college attainment. Using OECD data, we confirm an observed quantifiable association between the income shares of the working poor and the availability and take-up of vocational education (Aizenman et al. 2017).

By contrasting the education systems in the US and Germany, we suggest that subsidising more students to attend degree-granting colleges may not be an efficient way to deal with the declining real incomes of the working poor. Such a policy may induce private and public overinvestment in higher (degree) education by some segments of the population, with little observed returns.

Using different data sources for 21 countries, for the years 2003-2013, we first examine the cross-country evidence. Across these countries, the correlation between a measure of inequality and measures of vocational education is always negative. Estimating a panel model, and using a fixed-effects estimation,1 we find that both the relative size of the manufacturing sector and the share of vocational education are positively associated with the top 10% income share. In a standard trade model, both terms-of-trade adjustment and technological bias for skilled labour can give rise to increasing inequality. Interestingly, we find that an interaction of the relative size of the manufacturing sector and the share of vocational education is negatively associated with the top 10% income share. As the manufacturing sector becomes more important in a country’s income, unskilled labourers benefit relatively more from access to vocational education, thereby narrowing the income gap. Specifically, at a low level of manufacturing contribution, increasing vocational share is correlated with either an increase or only a small reduction in inequality, ceteris paribus. However, as manufacturing increases its relative share in the economy, incremental improvements in students’ access to vocational education are associated with larger declines in inequality. In order to examine the relative importance of tertiary versus vocational education in tackling inequality, we add the ratio of labour force with tertiary qualification and its interaction with manufacturing to our baseline model. Both vocational and tertiary education sector shares are positively correlated with rising inequality. Moreover, the interaction suggest that as manufacturing contributes more and more to the economy, vocational education appears to be a better complementary policy that can reduce inequality.

A case study: The US and Germany

A narrative gaining political momentum in the US has been that the decline in manufacturing employment is an outcome of globalisation (specifically NAFTA). According to this narrative, China and Germany are prime examples of countries benefiting from globalisation.

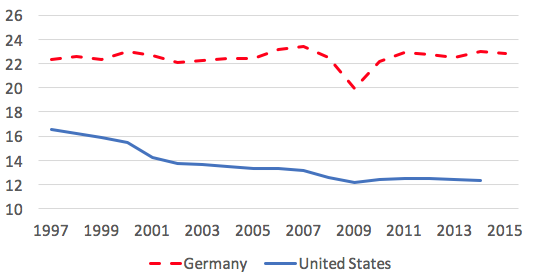

Figure 1 reports the manufacturing employment shares for Germany and the US, vividly showing that the trend decline in manufacturing employment is common to both countries. Both countries have experienced continuing employment declines – an annual rate of loss of 0.47% in Germany, and 0.38% in the US. Indeed, similar trends apply across other OECD countries, and even beyond the high-income countries to many emerging markets.2

Figure 1 Manufacturing as a percentage of value added in GDP

Source: OECD

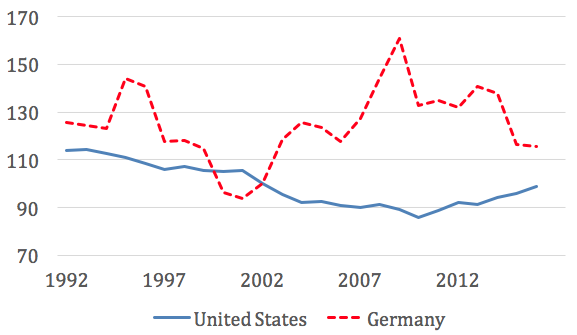

Remarkably, despite the decline in the manufacturing employment share in Germany, the manufacturing GDP value added share in Germany has been stable, at about 23%, recovering fully after a V-shape adjustment during and after the Global Crisis. In contrast, during the past two decades, the US experienced a drop of about 5% in manufacturing value added, at the same time that the manufacturing employment share dropped by 6%. When examining an index of real unit labor costs in the manufacturing sector for 2000-2012, we observe trends that are consistent with the superior performance of manufacturing in Germany: the real unit labour cost in the US dropped by more than 10% relative to Germany (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Indexed unit Labor costs in the manufacturing sector, US dollar basis, 1992-2016

Note: 2002=100.

Source: The Conference Board, International Labor Comparisons Program, May 2017

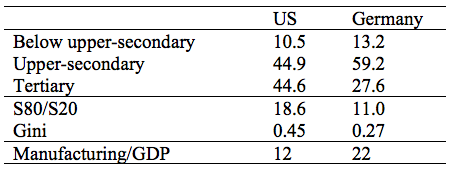

The differential manufacturing performance of these two countries may be the outcome of structural factors, as well as policies. While we cannot pin down a causal interpretation, we note several structural differences between the countries that we think are important. The educational attainment aggregate numbers of the two countries differ sharply – the labour force in Germany is relatively more replete with workers with an upper-secondary education, and the labour force in the US with those who have tertiary education credentials. The share of workers with an upper-secondary education in Germany exceeds that of the US by about 15% points, and the share of workers with a tertiary education in the US exceeds that of Germany by about 17% points (Table 1). The US labour force is more educated or more highly skilled.

Table 1 Education: Germany versus the US (% of population, average 2011-2015)

Source: World Development Indicator and Poverty and Equity Database, World Bank

The safety net in Germany is deeper and wider than in the US, and income inequality in the US is substantially higher than that in Germany. Given the relative success of German manufacturing, it is plausible that the Germany education system’s emphasis on vocational training fits the needs of modern manufacturing better.

While the manufacturing employment share has declined substantially in both countries, the shallower safety net in the US may explain why this issue has generated greater social impact there than in Germany. The first-ever decline in life expectancy in some parts of the US, and the growing despair of the displaced less-educated workers in the US – identified by Case and Deaton (2015, 2017) – may reflect this shallower safety net.

In the US, the public policy concern about overinvestment in four-year colleges largely concentrates on the for-profit sector (e.g. Deming et al. 2012). But this overinvestment is found in all parts of the system, and is partly driven by a lack of information about the distribution of the college premium in all types of institutions.3 There appear to be too many four-year colleges serving too many students, and too few institutions with a greater focus on vocational education and training.4

Vocational employment training (VET) in Germany is much more developed. The CESifo database on Institutional Comparisons in Europe (DICE) includes institutional details about VET found in many European countries. Germany starts to identify students who are struggling in the ‘academic’ track in lower-middle school, and has various mechanisms in place to assist these students to succeed in VET programmes; while in the US, assistance is available only for students once they drop out of a ‘normal’ high school. Vocational training after secondary school is almost only found if it is organised privately for specific professions. Rebalancing the tertiary education system in the US with more vocational training may not be a panacea.5 Yet, overlooking the need to align the education system with the demands of the real economy comes with growing personal and social costs.6

Conclusion

In another case study included in our paper, we compare Thailand and Vietnam (Aizenman et al. 2017). Vietnam spends twice as much as Thailand on vocation education, while inequality in both countries appear fairly constant in the past 30 years.

More generally, the quantitative evidence on the role of vocational training is imperfect, but both the limited cross-country evidence analysed here, and the comparisons we made, convince us that well-resourced and well-targeted vocational training can prove to be a better long-term investment in skill acquisition and can assist in ameliorating the difficulties faced by those workers whose prospects look, in many cases, to be quite bleak.

In the future, we hope to work on extensions that will examine (i) the importance of vocational training in the service sectors (as manufacturing employment is declining), (ii) more detailed accounting of the quality of vocational education, and (iii) the impact of vocational training on poverty.

References

Aizenman, A, Y Jinjarak, N Ngo and I Noy (2017) “Vocational Education, Manufacturing, and Income Distribution: International Evidence and Case Studies”, NBER Working Paper No. 23950.

Aizenman, A and I Noy (2012), “Reflections on the curious contrast of public policies between Germany and the US: Real estate versus human capital”, voxEU.org, 25 August.

Attanasio, O, A Guarin, C Medina and C Meghir (2017) “Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Youth in Colombia: A Long-Term Follow-Up”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2): 131-143.

Card, D, P Ibarrarán, F Regalia, D Rosas-Shady and Y Soares (2011), “The Labor Market Impacts of Youth Training in the Dominican Republic”, Journal of Labor Economics 29(2): 267-300.

Case, A and A Deaton (2015), “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century”, PNAS 112(49): 15078-15083.

Case, A and A Deaton (2017), “Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring.

Deming, D J, C Goldin, and L F Katz (2012), “The for-profit postsecondary school sector: Nimble critters or agile predators?”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(1): 139-163.

Forster, A G, T Bol, and H G van de Werfhorst (2016), “Vocational education and employment over the life cycle”, Sociological Science 3: 473-494.

Hanushek, E A, G Schwerdt, L Woessmann and L Zhang (2017), “General Education, Vocational Education, and Labor-Market Outcomes over the Lifecycle”, Journal of Human Resources 52(1): 48-87.

Looney A and C Yannelis (2015), “A crisis in student loans? How changes in the characteristics of borrowers and in the institutions they attended contributed to rising loan defaults”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2015(2): 1-89.

Ministry of Education and Research (2005), Reform of Vocational Education and Training in Germany.

Endnotes

[i] More information on the model and regressions is available in Aizenman et al. (2017), Tables 2-3.

[ii] Globalisation, thus, does not appear to be a zero sum game of winners and losers in the struggle for trade. It hard to see how globalisation can explain the almost universal declines in manufacturing employment.

[iii] The college premium is the return to college education in terms of additional lifetime income. We know very little about the distribution of these premiums at the lower end of the income distribution.

[iv] This mismatch is sustained by the skewed assistance scheme that is facilitated by the federal government. A Brookings study found that a large share of the growth in the number of students struggling to pay off their student loans is from students borrowing to attend for-profit schools (Looney and Yannelis 2015). These public policy concerns are magnified by the fact that student debt in the US is not erased if one declares bankruptcy, unlike credit card debt. Mortgage debt is even easier to walk away from. Hence, student debt is especially pernicious and damaging as it is more long-lasting.

[v] Notably, Hanushek et al. (2017) concluded that vocational education is harmful in the later phases of work careers - vocationally qualified workers are the first to be laid off after the age of 50 because their specific skills are likely to be outdated. Yet, Forster et al. (2016) noted that, while it may be true that people with vocational qualifications are less likely to be employed later in their career, this pattern may be unrelated to the way that vocational education is organised. Specifically, they argue that the warning of Hanushek et al. (2017) to the proponents of a German style vocational training system should imply that the late career disadvantage of vocational degrees would be more pronounced in countries with a large dual system (i.e. work- and school-based). Looking at the data, they did not find evidence of that difference. On the contrary, German-like education systems with a strong emphasis on dual tracks are characterised by less disadvantage late in the careers of vocationally qualified workers. The negative effect of vocational training at the end of the career are observable statistically only in countries that do not have dual-track systems, like the US and Canada.

[vi] We also note that the US mortgage debt crisis of 2008-2010, and the education debt overhang in the US may both be indicative of structural differences that led to over-investment in both real estate and in college education in the US relative to Germany. This over-investment may reflect structural factors such as the differential use in leverage in funding housing and education services in the two countries, the differential tax system, and the greater role of private and for-profits education in the US (Aizenman and Noy 2012).