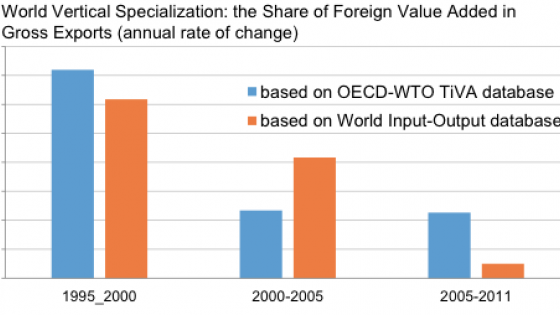

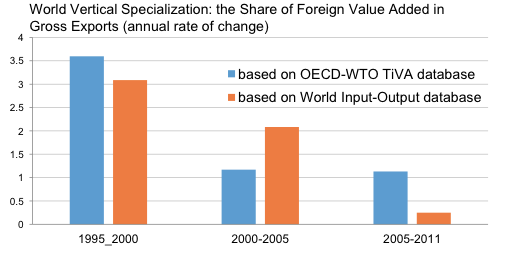

World trade grew at about 3% per annum in 2012-2015, which is much less than the pre-Crisis average of 7% for 1987-2007 and less than the growth of GDP. Previous work has shown that world trade is growing slowly not only because GDP growth is sluggish, but also because the long-run relationship between trade and GDP is changing (Hoekman 2015, Constantinescu et al. 2015). The elasticity of world trade to GDP was larger than 2 in the 1990s but closer to 1 and declining throughout the 2000s. Among the leading causes of this structural change in the trade-income relationship is a shift in vertical specialisation. The long-run trade elasticity increased during the 1990s, as production fragmented internationally into global value chains (GVCs), and decreased in the 2000s as this process decelerated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of foreign value added in gross exports

Note: Annual rate of change is computed using the compound annual growth rate formula.

Source: Constantinescu et al. (2016).

Does the global trade slowdown matter?

Economists disagree. Some believe that the slowing down of global trade has no real consequences. For instance, Paul Krugman noted that “[t]he flattening out is neither good nor bad, it’s just what happens when a particular trend reaches its limits” (Krugman 2014). Others take the opposite view. For instance, in a speech as governor of the Central Bank of India, Raghuram Rajan concluded that “[w]e are more dependent on the global economy than we think. That it is growing more slowly, and is more inward looking, than in the past means that we have to look to regional and domestic demand for our growth” (Rajan 2014).

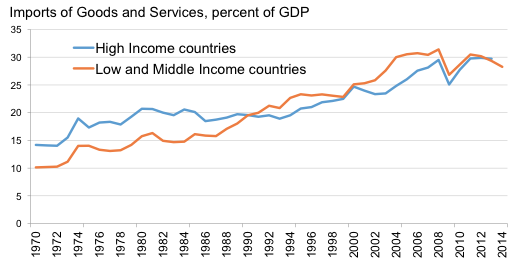

Both views have elements of truth, but neither may be completely right. On the one hand, the impact of the trade slowdown should not be overstated. Most economies are more open today in terms of the share of trade in GDP than they were in the 1990s (Figure 2). In so far as openness per se is associated with dynamic benefits, trade will continue to foster growth. On the other hand, there is a risk of understating the implications of the trade slowdown. If the expansion of trade growth relative to GDP growth in the 1990s contributed to countries’ economic growth, one may suspect that the flattening of this trend will imply that the contribution of trade to the growth process will be lower.

Figure 2. Imports and goods and services as a percentage of GDP

Source: World Bank Development Indicators.

In recent work, we make a first attempt to investigate the economic consequences of the changes in the trade-income relationship (Constantinescu et al. 2016). We focus on two channels: the demand side ‘Keynesian’ concern is that sluggish world import growth may adversely affect individual countries’ economic growth by limiting opportunities for their exports; the supply side ‘Smithian’ concern is that slower trade may diminish the scope for productivity growth through increasing specialisation and diffusion of technologies. In particular, a slower pace of GVC expansion may imply diminishing scope for productivity growth through a more efficient international division of labour and knowledge spillovers.

The Keynesian concern

The mechanism underlying the Keynesian concern is that a country’s GDP growth depends on its export growth and that, in turn, export growth depends on the growth rate of the world economy. The worry is that any growth in world income will translate into less growth in a country’s exports and hence in a country’s GDP today than it did during the 1990s. To capture these relationships, we estimate two distinct elasticity measures. The first one is the elasticity of a country’s exports with respect to world GDP, which tells us how closely tied a particular country’s exports are to world income. The second is the elasticity of the GDP of a country with respect to its exports, which measures how a country’s GDP changes when its exports change.

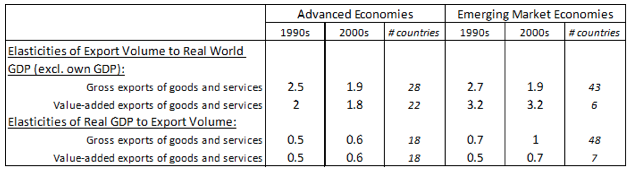

Table 1 reports the average of the country-specific elasticities for advanced economies and for developing economies. When we look at the elasticities in gross terms, we find a decline of the responsiveness of exports to world GDP and an increase in the responsiveness of domestic GDP to exports. These changes are more pronounced for developing than for developed economies. However, when we use value added exports, which are more relevant for the demand-side mechanism, the change in estimated elasticities is smaller and not statistically significant (although a qualification is that value added trade data are available for a shorter period and fewer countries).

Table 1. The responsiveness of exports to world GDP

Source: Constantinescu et al. (2016).

Bringing together these findings, there is no clear evidence that the diminished responsiveness of world trade to world GDP has weakened the demand-side transmission channel of either advanced or developing economies. But more work and data are needed to assess the extent of the Keynesian concern.

The Smithian concern

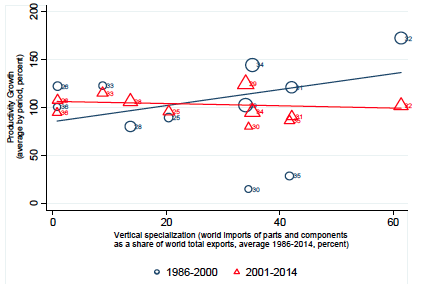

We try to assess the Smithian concern by focusing on the growth implication of a slowing pace of GVC growth. Figure 3 presents some motivating evidence. The figure plots the world average labour productivity growth by sector for the 1990s and the 2000s as a function of (a measure of) the sector’s vertical specialisation. In the 1990s, when global value chains were expanding, productivity growth tended to be higher in more vertically fragmented sectors. This association, however, disappears in the 2000s. Assuming that there was no change across the two periods in the nature of the relationship between changes in productivity and changes in vertical specialisation, the evidence in Figure 3 suggests that productivity growth may have been affected by a slower pace of expansion in global value chains.

Figure 3. Vertical specialisation and productivity growth

Notes: Industry codes based on ISIC Rev. 3; productivity normalised using average industry productivity by decade; weights represented by value added.

Source: Constantinescu et al. (2016).

Exploiting this intuition, we try to quantify the supply-side effect of the global trade slowdown in two steps. First, we use estimates from Constantinescu et al. (2016b) of the impact of (forward and backward) vertical specialisation on productivity growth at the country-sector level. The estimates were obtained from a panel regression run on country-industry specific annual data from the World Input Output Database (Timmer et al. 2015). The key finding is that backward linkages have a positive impact on productivity growth, although the effect is not large. A one standard deviation increase in backward specialisation increases productivity growth of the average sector by 0.06%.

We next use this estimate of the impact of vertical specialisation on labour productivity growth to quantify the supply-side effect of the trade slowdown. Specifically, we assess the extent to which a slower pace of GVC growth in recent years has contributed to sluggish productivity growth. Actual yearly growth in labour productivity has decreased over time from 9% in the period 1995-2003 to below 5% in the period 2004-2011. The estimates reported above suggest that the yearly contribution of (backward) vertical specialisation to productivity growth declined by more than a half from 0.11 in the period 1995-2003 to 0.05 in the period 2004-2011.

Conclusion

This is a first attempt to analyse the consequences of the global trade slowdown. Our goal is not to provide definitive answers, but to provoke research and debate. The preliminary evidence suggests that the declining world trade elasticity matters for countries’ performance, although the quantifiable effects do not appear to be large.

More work is needed. On the demand side, we have made strong assumptions on the relationship between the variables involved. These are useful reduced forms, but they are not a substitute for models that account for the complex structural relationships between these variables. On the supply side, we have focused on a narrow issue: the impact of the slowing pace of expansion of vertical specialisation on productivity growth. Because the slowing pace of GVC growth is an important factor of the trade slowdown, this initial focus appears justified. However, future work may want to take a broader perspective and evaluate other supply-side channels, such as technology spillovers or enhanced competition.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group.

References

Constantinescu, Mattoo and Ruta (2016), “Does the Global Trade Slowdown Matter?”, forthcoming, Journal of Policy Modeling.

Constantinescu, Mattoo and Ruta (2015), Explaining the Global Trade Slowdown, VoxEU, January 2015.

Constantinescu, Mattoo and Ruta (2016b), Does Vertical Specialization Increase Productivity Growth?, Work in Progress

Hoekman, Bernard. 2015. The Global Trade Slowdown: A New Normal? VoxEU.org e-Book. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Krugman, Paul (2014), “Flattening Flattens”, New York Times Blog, 3 November 2014.

Rajan, Raghuram (2014), “Make in India, Largely for India”, Talk delivered at the Bharat Ram Memorial Lecture on December 12, 2014.

Timmer, Marcel P., E. Dietzenbacher, B. Los, R. Stehrer, and G. J. de Vries (2015), "An Illustrated User Guide to the World Input–Output Database: the Case of Global Automotive Production", Review of International Economics 23, pp. 575–605.