The EU fiscal governance landscape is quite complex. Within this landscape, the national independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) are becoming increasingly visible. IFIs do not have any decision power of their own. However, based on thorough analysis they incentivise governments to follow better and more transparent fiscal policies. In addition, because they are mandated to produce or endorse the official macroeconomic projections, they help to reduce systematic biases in these projections, thereby leading to more reliable fiscal policies.

The OECD (2014) has set out a collection of principles for well-functioning IFIs, which can be summarised under a number of broad headings. These include local ownership, independence, a mandate set in higher-level legislation and linked to the budget process, resources commensurate with the mandate, sufficient accountability to the legislature, complete and timely access to all relevant information (including methodologies and assumptions), full transparency in their work, and effective communication channels with media and relevant stakeholders.

Following its recent economic governance review, the European Commission (2022) issued a Communication with a proposal that countries submit a fiscal-structural path following a reference adjustment path established by the Commission on the basis of a debt sustainability analysis.

As the Commission writes, “Independent fiscal institutions would play an important role in each Member State in assessing the assumptions underlying the plans, providing an assessment on the adequacy of the plans with respect to debt sustainability and country-specific medium-term goals, and monitoring compliance with the plan”.

Building on the Communication, the ensuing European Commission (2023b, 2023c) legislative proposals of April this year do indeed foresee an expansion of the role of the IFIs. However, the Commission no longer envisages the IFIs assessing the assumptions underlying Member States’ plans when they are devised. The proposals also fall short of those in Beetsma et al. (2022), in which fiscal surveillance of countries adhering to the SGP would be largely delegated to the national level, with the IFI having an enhanced monitoring role.

Still, the Commission proposals improve upon the current situation. The proposed replacement of the SGP’s preventive arm foresees IFIs assessing budgetary outturns data in relation to the net primary expenditure path set in the fiscal-structural plan, while a proposed revision of Council Directive 2011/85/EU envisages extending the role of IFIs to producing or endorsing the budgetary forecasts underlying medium-term planning. IFIs would also undertake a debt sustainability assessment underlying the medium-term planning or endorse such an assessment by the budgetary authorities. Further, they would monitor compliance with country-specific numerical fiscal rules and the EU fiscal framework, and participate in reviews of the national budgetary framework.

At the moment, these are still proposals that need the agreement of the Member States’ governments to be adopted (possibly following negotiation). What is the political scope for giving IFIs a greater role in the revised framework? IFIs monitor and sometimes criticise the fiscal policies of their own government. Quite naturally, a government may not be so fond of its own IFI and perceive it as a nuisance. For example, the IFI may criticise the input figures or methodologies used by the Ministry of Finance to produce its forecasts. Indeed, in its Conclusions of 14 March 2023 the Ecofin Council has shown itself less than enthusiastic about enhancing the IFIs’ role in the revised governance framework, by writing “IFIs should not play a role in the design phase of the national plans”.

This lack of support from the Ministries of Finance may well go against their own interests (Beetsma 2023). The current situation resembles the pay-offs of a prisoner’s dilemma. The government of some Member State X may prefer to weaken the role of its own IFI, but it benefits from a strong role of IFIs in other Member States,

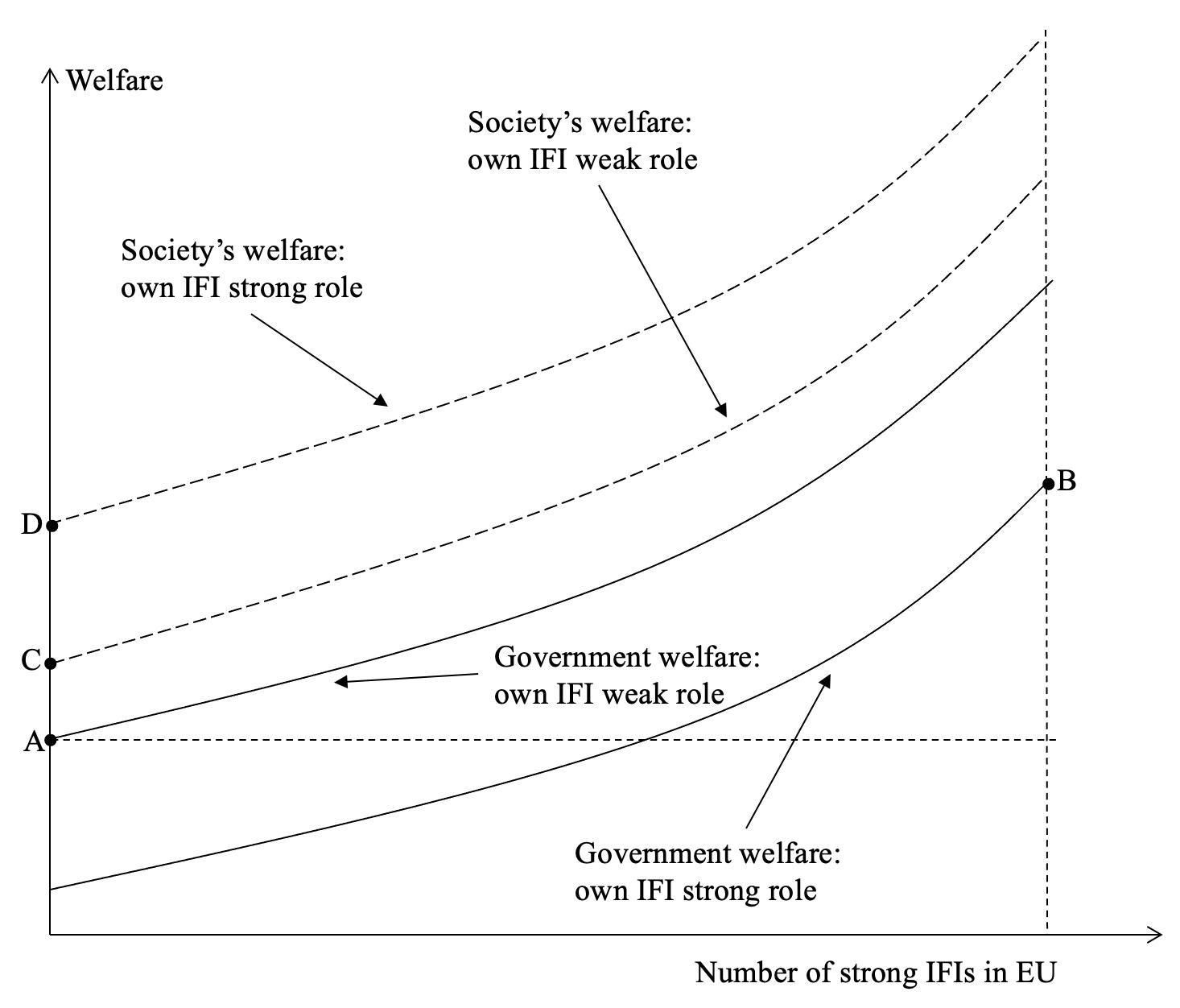

because this leads to better fiscal policies elsewhere with more benign cross-border spill-over effects (such as reduced threats of a sovereign debt crisis). Hence, collectively, governments would all be better off with a set of IFIs with strong roles throughout the EU than with each IFI having a weak role. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which compares point A where all IFIs have a weak role with point B where all IFIs have a strong role.

Figure 1

However, the benign outcome in point B does not automatically result, because each government has an incentive to unilaterally deviate from this outcome. The ‘equilibrium’ is therefore a situation in which each IFI has a weak role. So, how can we move away from this Pareto-inferior outcome to a situation in which all IFIs have a strong role?

A possibility would be for the European Commission and the European Parliament to promote a broader role for the IFIs and raise the price for watering down their role in the eventual legislative outcomes. Assuming that both institutions take a sufficiently pan-European view, they should a priori support the broader role of the IFIs. This would generally also be in their own interest. In the case of the Commission, the IFI may complement its work by providing inputs about its own country, for example when it comes to the plausibility of the assumptions underlying the government’s projections or the treatment of one-offs and the like – it is simply impossible for the Commission to have sufficiently detailed knowledge of each individual EU economy (see also Kopits 2010, 2023).

The European Parliament benefits from the additional budgetary transparency provided by the IFI, because the European Parliament does not get any budgetary information beforehand, and may find it hard to interpret such information.

Of course, reality is more complicated than the simple game portrayed above with each government assigning their IFI a weak role. For example, Italy, Portugal and Spain feature IFIs that have had the courage to take a tough stance against their own governments on various occasions. It is interesting that precisely these very high-debt countries have such brave IFIs, while some of the ‘more fiscally disciplined’ countries did not invest much in their IFI’s, maybe because they thought this was not necessary. However, this seems a miscalculation of these countries’ own interests, because they benefit from responsible foreign fiscal policies that avoid negative cross-border spillover effects. By giving their own IFI a strong role, they set a good example for countries with less disciplined fiscal policies.

If governments indeed manage to agree, IFIs would need to be brought up to speed with their enhanced mandates. A survey by the Network of EU IFIs (2022b) finds that the IFIs assess themselves as generally having a rather strong capacity to perform their core tasks, i.e. assessing/endorsing the official macroeconomic forecasts and assessing ex-ante or ex-post compliance with the EU fiscal rules. However, each of the various core tasks features at least some institutions struggling to fulfil them. The Network of EU IFIs (2022a, 2022c) has called for higher minimum standards for each country to apply to its own IFI, and these will become even more important with its expanded role in the revised governance framework. The minimum standards pertain in particular to resources, independence, access to information, strengthening of comply-or-explain, proper legal enshrinement of their tasks, and freedom to publish what they deem necessary.

Minimum standards can be raised by giving Member States’ legislatures a greater say in the design of their IFI, because the legislature represents the interest of society at large, rather than the narrower interest of a government under pressure to produce short-term benefits for its own constituency. Points C and D in Figure 1 demonstrate the situation in which the legislature (society) is better off with their own country’s IFI having a strong role, while the other countries’ IFIs all have a weak role. Society’s welfare increases further when more IFIs in the EU acquire a strong role.

It is important to realise, however, that raising minimum standards is one thing. They also need to be enforced. If a country fails to comply with these minimum standards, the IFI needs to raise the issue with the legislature, and with the European Commission, which would need to enforce the (higher) minimum standards that countries have agreed upon. This would likely be most effective when they do this as a collective via their Network whenever one of its members is under threat.

Author’s note: I thank, without implicating, Sebastian Barnes, Massimo Bordignon, Laszlo Jankovics, Martin Larch, Niels Thygesen, Jeromin Zettelmeyer and Richard van Zwol for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this column. The views expressed here are the personal views of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions he is affiliated with.

References

Arnold, N, R Balakrishnan, B Barkbu, H Davoodi, A Lagerborg, W R Lam, P Medas, J Otten, L Rabier, C Roehler, A Shahmoradi, M Spector, S Weber and J Zettelmeyer (2022), “Reforming the EU Fiscal Framework: Strengthening the Fiscal Rules and Institutions”, IMF Discussion Paper 2022/014.

Barnes, S (2023), “Working in the same or different directions? Assessing the relationship between EU and domestic fiscal frameworks”, paper presented at the Fifth Annual Conference of the European Fiscal Board, 11 May.

Beetsma, R, M Bordignon, X Debrun, M Szczurek and N Thygesen (2022), “Making the EU and National Budgetary Frameworks Work Together”, VoxEU.org, 13 September.

Beetsma, R (2023), “Strengths and weaknesses of independent advisory fiscal institutions in the EU economic governance framework”, In-depth Analysis at request of ECON committee of the European Parliament, May.

Blanchard, O, A Sapir and J Zettelmeyer (2022), “The European Commission’s fiscal rules proposal: a bold plan with flaws that can be fixed”, Bruegel Blog post, 30 November.

Buti, M, J Friis and R Torre (2023), "The emerging criticisms of the Commission proposal on reforming the European fiscal framework: A response”, VoxEU.org, 10 January.

European Commission (2022), “Communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework”, COM(2022) 583 final, 9 November.

European Commission (2023a), “Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97”, COM (2023) 240 final, 26 April.

European Commission (2023b), “Proposal for a Council Regulation amending Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure”, COM (2023) 241 final, 26 April.

European Commission (2023c), “Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 2011/85/EU on requirements for budgetary frameworks of the Member States”, COM(2023) 242 final, 26 April.

Kopits, G (2010), “Brussels Can’t Monitor 27 Budgets”, Wall Street Journal, 11 October.

Kopits, G (2023), “Strengthening EU Independent Fiscal Institutions”, paper presented at the Fifth Annual Conference of the European Fiscal Board, 11 May.

Micossi, S (2023), “On the Commission’s orientations for a revised economic governance in the EU”, VoxEU.org, February 23.

Network of EU IFIs (2022a), Strengthening the role of EU national IFIs: Minimum standards and mandates, 21 February.

Network of EU IFIs (2022b), Strengthening the role of EU national IFIs: Enhancing the contribution of national IFIs at EU level, 21 February.

Network of EU IFIs (2022c), The Capacity of National IFIs to Play an Enhanced Role in EU Fiscal Governance, 17 October.

OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Independent Fiscal Institutions, Public Governance Committee, Paris.

Wyplosz, C (2022), “Reform of the Stability and Growth Pact: The Commission’s proposal could be a missed opportunity”, VoxEU.org, 17 November.