The ageing of populations is putting substantial pressure on pension systems worldwide. As an answer to this demographic pressure, pension reforms – typically a combination of changes to the retirement age, the benefit accrual process, and benefit generosity – have become central to the political agendas of many governments. Such reforms not only affect current pensioners, but also alter the incentives to work. They typically encompass an income effect by changing expected pension wealth, as well as a substitution effect by changing the returns to working. Understanding the behavioural responses of current workers to pension reforms is crucial for getting a full picture of their budgetary implications. A large literature has investigated the effects of pension reforms on labour supply close to retirement, focusing especially on changes in actual retirement behaviour (for reviews, see Gruber and Wise 1999, Krueger and Meyer 2002, Blundell et al. 2016). Less is known about the responses of workers further away from retirement; existing studies examine the role of changes in the statutory retirement age (Hairault et al. 2010, Carta and De Philippis 2021), the contribution-benefit link (French et al. 2022), and pension rules more generally (Bovini 2019).

In a recent paper (Artmann et al. 2023), we analyse whether changes in pension wealth have an effect on the labour supply of workers who are not yet close to retirement age. The specific setting we analyse enables us to isolate a pure income effect, since the reform does not encompass any changes in the returns to working. This setting is thus ideal to understand whether workers adjust their labour supply in response to changes in future pension wealth.

The German pension treatment of mothers

In the German pension system, mothers receive pension points, which later translate into pension income, for having children. Yet, there is a marked discontinuity in this policy (the so-called ‘Mütterrente’, or mothers’ pension): for children born on or after 1 January 1992, mothers receive three pension points; previously, for children born before 1 January 1992, mothers received only one pension point. This discontinuity played a major role in the political debate ahead of the German elections in September 2013, in which the Christian Democrats announced that they would alleviate this unequal treatment in a potential future government. Indeed, after they won the election, their coalition agreement with the Social Democrats from December 2013 stated that the pension points for mothers of children born before 1 January 1992 would change from one point to two points per child from July 2014 onwards. This reform increased the pension wealth of mothers with children born before 1992 by €3,380 per child in present discounted value, corresponding to 4.4% of the average pension wealth of these mothers, while it left the pension wealth of mothers with children born in 1992 or later unchanged. This setting enables us to analyse the income effects of pension wealth on labour supply in a difference-in-differences design, using mothers of children born in 1992 or later as the control group for the treated mothers, whose children were born in 1991 or before.

Income effects of pension wealth

To analyse whether treated mothers adjusted their labour supply after the increase in their pension wealth, we refer to the Integrated Employment Biographies of the German Institute for Employment Research (IAB). These contain the full working histories of all German workers subject to the social security system. We impute child births in the data following the methodology of Müller and Strauch (2018), which works very well for capturing the births of first children. To ensure comparability of the treatment and control groups, we then compare the labour supply behaviour of mothers whose first children were born between October and December 1991 (the treated group) to the labour supply behaviour of mothers whose first children were born between January and March 1992 (the control group), before and after the reform announcement in December 2013.

These mothers were on average 50 years old at the time of the reform, thereby still substantially younger than the statutory retirement age of 67.

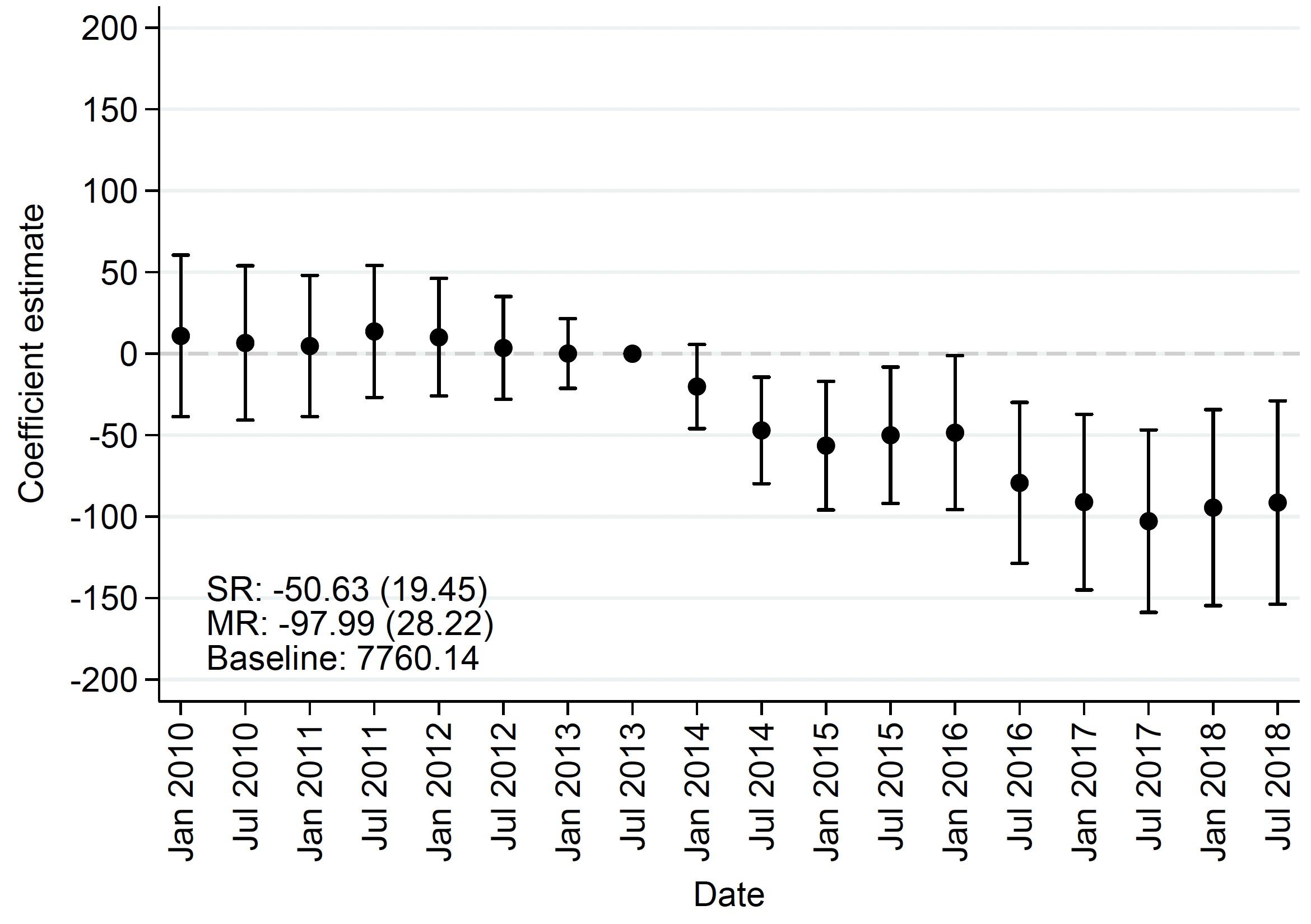

As Figure 1 shows, total unconditional earnings of both groups of mothers evolve virtually identically in the eight semesters preceding the reform, namely from the first semester of 2010 (indicated as Jan 2010) to the second semester of 2013 (indicated as Jul 2013). However, immediately after the announcement of the reform, in December 2013, the unconditional earnings of treated mothers fall behind those of the control group, and this gap widens over time. In the first 2.5 years after the reform, unconditional earnings of the treated group fall by €101 annually (or 0.7% of the pre-reform mean unconditional earnings), and in the following 3 to 5 years even by €196 annually (or 1.3%). We therefore find statistically significant responses to the increase in future pension wealth: treated mothers reduce their (unconditional) earnings.

Figure 1

Notes: Dots represent point estimates and capped vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on robust standard errors clustered at the individual level from a regression of unconditional labour earnings on the interaction of a treatment dummy and a semester dummy, controlling for calendar time and individual fixed effects. The graph also reports estimates of the short-run effect over the 1–2.5 years after the 2014 reform (SR) and of the medium-run effect over the 3–5 years after the reform (MR), with robust standard errors clustered at the individual level in parentheses. The baseline statistic is the average value of the outcome in the treatment group in July–December 2013.

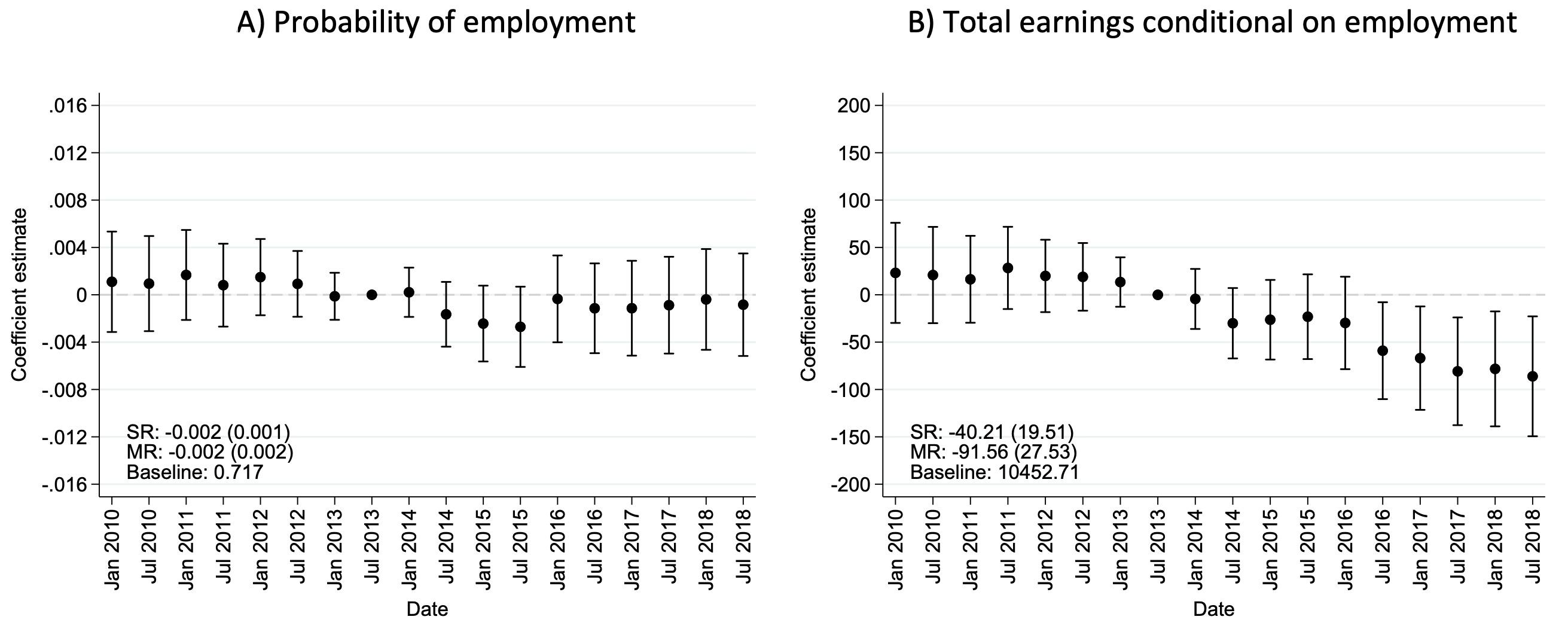

Are these responses along the extensive or the intensive margin? In other words, do treated mothers stop working, or do they reduce their hours worked? Figure 2 gives an answer to this question, differentiating between the probability of being employed in Panel (A), and labour earnings conditional on being employed in Panel (B). In fact, we find no response along the extensive margin; instead, the entire response occurs along the intensive margin: treated mothers don’t stop working, but reduce their earnings conditional on working. In line with this, we also find that the probability of working full-time, conditional on working, falls after the reform.

Studies that focus on labour supply close to retirement usually show extensive margin effects; further away from retirement, however, intensive margin responses seem to be more important.

Figure 2

Notes: Dots represent point estimates and capped vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on robust standard errors clustered at the individual level from a regression of unconditional labour earnings on the interaction of a treatment dummy and a semester dummy, controlling for calendar time and individual fixed effects. Each graph also reports estimates of the short-run effect over the 1–2.5 years after the 2014 reform (SR) and of the medium-run effect over the 3–5 years after the reform (MR), with robust standard errors clustered at the individual level in parentheses. The baseline statistic is the average value of the outcome in the treatment group in July–December 2013.

To translate the effects into the marginal propensity to earn (MPE) out of pension wealth in a given period, we equally allocate the wealth windfall over time until retirement, which gives us an MPE of -0.54: an extra euro of pension wealth leads to a 54 cent reduction in labour earnings in middle-age.

Heterogeneity and spillovers

We further investigate heterogeneity in the effects, and find that mothers in jobs with higher expected returns to tenure are less likely to cut back their labour supply. By contrast, the physical strain of an occupation does not play a role in the response. Mothers with higher pre-reform pension wealth, be it personal or cumulated household pension wealth, react more strongly to the reform. Liquidity constraints, as proxied by the partner’s pre-reform labour earnings, seem to mute responses to the reform.

For a subsample of the data for which we can match husband and wife, we can also investigate the behaviour of the husbands of the affected mothers. While the point estimates indicate some household-level spillovers, with husbands of the treated mothers also reducing their conditional earnings, most are not statistically significant.

Conclusion

The ageing of the population puts a strain on government budgets, and pension reforms are therefore at the forefront of many policy debates. Pension reforms affect not only the expenditure side but also the revenue side of budgets: as our study shows, workers adjust their labour supply in response to the income effects caused by changes to future pensions. A back-of-the envelope calculation implies that for each euro of increased pension due to the reform, government revenue fell by 31 cents due to lower income tax and social security contribution payments, a substantial fiscal externality. At the same time, assuming symmetry of our results would imply that reforms that reduce pension generosity lead to increased labour supply through the income effect, thereby amplifying the positive effect of such reforms on government budgets.

References

Artmann, E, N Fuchs-Schündeln and G Giupponi (2023), “Forward-Looking Labor Supply Responses to Changes in Pension Wealth: Evidence from Germany”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18149.

Blundell, R, E French and G Tetlow (2016), “Retirement Incentives and Labor Supply”, Handbook of the Economics of Population Aging, vol. 1, 457–566.

Bovini, G (2019), “Life-Cycle Labor Supply and Social Security Wealth: Evidence from the 1995 Italian Pension Reform”, London School of Economics and Political Science Working Paper.

Carta, F and M De Philippis (2021), “Working Horizon and Labour Supply: The Effect of Raising the Full Retirement Age on Middle-Aged Individuals”, Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area Temi di discussione, working paper 1314.

French, E, A S Lindner, C O’Dea and T A Zawisza (2022), “Labor Supply and the Pension-Contribution Link”, NBER Working Paper 30184.

Gruber, J and D Wise (1999), “Social Security and Retirement around the World”, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hairault, J-O, T Sopraseuth and F Langot (2010), “Distance to Retirement and Older Workers’ Employment: The Case for Delaying the Retirement Age", Journal of the European Economic Association 8(5): 1034–76.

Krueger, A B and B D Meyer (2002), “Labor Supply Effects of Social Insurance”, Handbook of Public Economics, vol. 4, 2327–92.

Müller, D and K Strauch (2017), “Identifying Mothers in Administrative Data”, FDZ-Methodenreport 13/2017 (en).