The cohorts that entered the labour market in Japan during the prolonged recession from 1993 to 2004 are called the ‘ice age cohorts’, as they experienced very bad labour market conditions at their entry. Today, it is widely recognised that these cohorts have had less stable employment conditions and earned lower wages than older cohorts. Given the labour shortage in Japan due to the shrinking youth population, these ice age cohorts attracted some attention in the late 2010s as a potential source of labour. The government launched a package of support programmes in 2019 to help match unemployed and under-employed workers from these cohorts with good employment opportunities.

While the gap in employment stability and economic wellbeing between the ice age cohorts and the older cohorts is well known, few comparisons have been made between the ice age cohorts and younger cohorts who entered the labour market during the recovery period. These younger cohorts who graduated in the mid-2000s are not considered ice age cohorts, despite the higher unemployment rate they faced at entry than the older half of the ice age cohorts – probably because government programmes tend to define their targets as those who graduated from schools during 1993–2004.

Scarring effects of labour market conditions at entry

Labour market conditions at entry (graduation from school) have persistent effects on employment and earnings in subsequent years. Such ‘scarring effects’ are observed in many countries, with varying magnitude and persistency across countries (von Wachter 2020, Kawaguchi and Murao 2014). In Japan, the effects are relatively large and persistent. Indeed, studies using data from cohorts who graduated in the 1990s or earlier find that entering the labour market during a recession has persistent negative effects on employment and earnings for Japanese men. Ohtake and Inoki (1997), who produced one of the earliest studies in Japan, find a negative correlation between the index of labour market slackness at entry and earnings, using data for male full-time workers in 1970–90s. Genda et al. (2010) provide evidence for the negative effects of the high unemployment rate at entry using a more rigorous empirical model.

Why was the scarring effect persistent in Japan? The entry-level job market in Japan is characterised by an immediate transition from school to full-time work. The so-called school-based hiring system, mediated by high schools, contributed to a relatively low unemployment rate and high full-time employment rate among young high school graduates in Japan.

While colleges, unlike high schools, do not intervene in the job market except for highly specialised STEM occupations, the market for new college graduates is clearly separated from the rest of the labour market because many firms have a strong preference for new graduates when hiring inexperienced workers. Thanks to this strong preference for new graduates, the full-time employment rate of new college graduates in Japan is also high.

The downside of this smooth transition from school to work is, however, the limited access to good jobs for inexperienced workers who are not recent graduates. It is aggravated by the dual structure of regular and non-regular employment. Kondo (2007) and Hamaaki et al. (2013) show that the failure to obtain a regular full-time job upon graduation lowers the likelihood of having a regular full-time job in subsequent years, implying that a recession at entry would lower the long-run regular employment rate of the affected cohort.

Given such studies, the persistent gap between the ice-age cohorts and older cohorts who enter the labour market during the so-called bubble economy is often understood as a scarring effect of business cycle conditions at entry. However, the empirical studies use data from cohorts who entered the labour market in the 1990s or earlier. Despite the lack of empirical evidence with updated data, economists and policymakers take it for granted that the ice-age cohorts are suffering from the scarring effect of a recession at entry, blaming the rigidity of the Japanese labour market for employment disparities. In my paper (Kondo 2023), I reconsider such interpretations with data on younger cohorts who entered the labour market during the mid-2000s recovery period.

Post-ice age cohorts do not perform better

I define five cohort groups based on the year of graduation:

- 1987–92: the bubble economy cohorts

- 1993–98: the older half of the ice age cohorts

- 1999–04: the younger half of the ice age cohorts

- 2005–09: the post-ice age cohorts

- 2010–13: the global great recession cohorts

The unemployment rate at entry was highest for the 1999–04 younger half of the ice age cohorts, followed closely by the 2010–13 global great recession cohorts. The post-ice age group who graduated in 2005–09 faced lower unemployment rates than these two groups, but higher unemployment rates than the 1993–98 older half of the ice age cohorts. The 1987–92 bubble economy cohorts entered the labour market during a boom.

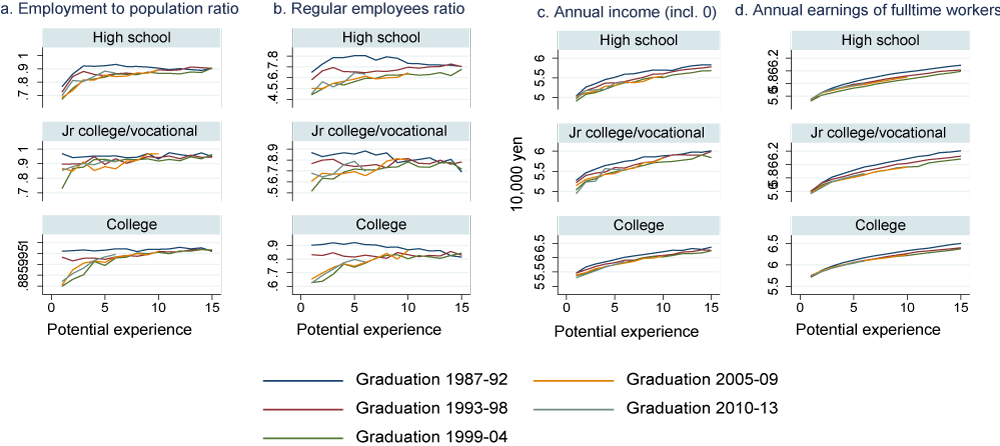

Figure 1 presents the potential experience profiles of four outcome variables by the five cohort groups and three levels of educational background. Taking together, these graphs imply substantially more stable employment and higher earnings for cohorts who entered the labour market before the ice age than during the ice age. The gap between the older and younger halves of ice-age cohorts is comparable to the gap between the bubble economy cohorts and the older half of the ice age cohorts.

Figure 1 Potential experience profiles by cohort group

Source: Kondo (2023).

Furthermore, we see no clear sign of recovery for the post-ice age cohorts compared to the ice-age cohorts. The trends in employment and earnings differ on one point: the gap in employment reduces gradually, but the gap in earnings is not reduced even 15 years after graduation.

Scarring effects became weaker after the ice age

Despite the recovery in the macro-level unemployment rate, the employment rate, the regular employee ratio, and income unconditional on employment of the post-ice age cohorts are almost as low as that of the younger half of the ice age cohorts, who faced the worst labour market conditions at entry. It implies that better labour market conditions at entry may no longer have positive long-term effects on employment and earnings, that is, the scarring effect may have become weaker since after the job market ice age.

My findings confirm this weakening of the scarring effects after the ice age. Specifically, I estimate the same empirical model as Genda et al. (2010) with older and younger subsamples and compare the size and persistence of the scarring effects. I find that the scarring effects of a recession at entry have become weaker and are no longer statistically significant for cohorts who graduated from schools during and after the job market ice age.

Among the various potential factors behind this change, increased job mobility may have reduced the persistence of the initial shock. Also, the decreased supply of workers who enter the labour market right after high school may have affected high school graduates. Although this is speculative, the prolonged recession may have triggered more permanent, structural changes that suppress the earnings of young workers, even for the cohorts who faced relatively tight labour market conditions at entry.

The Japanese labour market has often been characterised by very strong and persistent scarring of labour market conditions at entry. However, this may no longer be the case. On the one hand, the weakened scarring effects imply that, at the individual level, it has become more feasible for young workers to catch up, even if they were subject to a bad match at labour market entry. The downside of that same condition is that the advantage of obtaining a good job upon graduation due to the labour market tightness may no longer continue. For better or worse, the Japanese labour market has become more fluid since the 1990s.

Editor’s note: The main research on which this column is based (Kondo 2023) first appeared as a discussion paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Genda, Y, A Kondo, and S Ohta (2010), “Long-term effects of a recession at labor market entry in Japan and the US”, Journal of Human Resources 45(1): 157–96.

Hamaaki, J, M Hori, S Maeda, and K Murata (2013), “How does the first job matter for an individual’s career life in Japan?”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 29(C): 154–69.

Kawaguchi, D, and T Murao (2014), “Labor-market institutions and long-term effects of youth unemployment”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 46(S2): 95–116.

Kondo, A (2007), “Does the first job really matter? State dependency in employment status in Japan”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 21: 379–402.

Kondo, A (2023), “Scars of the job market ‘Ice-Age’”, RIETI Discussion Paper 23-E-042.

Ohtake, F, and T Inoki (1997), “Rodo-shijo ni okeru sedai koka (Cohort effects in the labor market)”, in K Asako, N Yoshino, and S Fukuda (eds.), Gendai macro keizai bunseki – tenkanki no nihon keizai, University of Tokyo Press.

von Wachter, T (2020), “The persistent effects of initial labor market conditions for young adults and their sources”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(4): 168–94.