The importance of returning to school later in life is generally understood. The 2023 Economic Report of the President (White House 2023) states that in the US over one-third of enrolled undergraduates are 25 or older. Post-secondary education institutions offer programmes tailored to returning or newly enrolled adults, such as the Columbia School of General Studies, or the Return to College Program of Bard College. However, since it is widely believed that the share of late college graduates is tiny, most research focuses on early graduates or assumes away the existence of late bloomers (Mincer 1974, Becker 1994, Keane and Wolpin 1997, Lee and Wolpin 2006). Consequently, we know relatively little about the late bloomers, their economic incentives and career goals.

Understanding late bloomers matters for the wider policy debate for several reasons. First, late bloomers may contribute to the changes in the gender and race gaps in education. These education gaps are well studied (see Bozzano and Bertocchi 2020 for a historical perspective on the gender education gap, and Lee 2002 on the racial gaps in education), but the contribution of late bloomers to the evolution of these gaps has not been examined. Second, late bloomers may have lower returns to education than early graduates, implying that classic Mincer regressions that estimate the value of college education (see Mogstad et al. 2014 for an overview) are in general biased. Further, the changing share of late bloomers can contribute to the evolution of the college wage premium (Bianchi 2014, Rustichini et al. 2022).

Late bloomers and their contribution to the aggregate college share increase

In a a recent paper (Bárány et al. 2023), we document that the continued education of individuals late into their lives is a robust, persistent, and widespread phenomenon. According to US Census data, the share of college-educated individuals increases within birth cohorts as they age. For example, at age 24 only 10.2% of the 1936 birth cohort had a college degree, by age 64 this fraction went up to 18.9% (for the 1966 birth cohort the corresponding numbers are 19.8% and 31.5%, respectively). Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), we establish that the increasing share of college-educated individuals within a cohort as it ages is not the result of differing immigration or mortality patterns by age across education groups, but the result of older adults enrolling and completing college programmes over time.

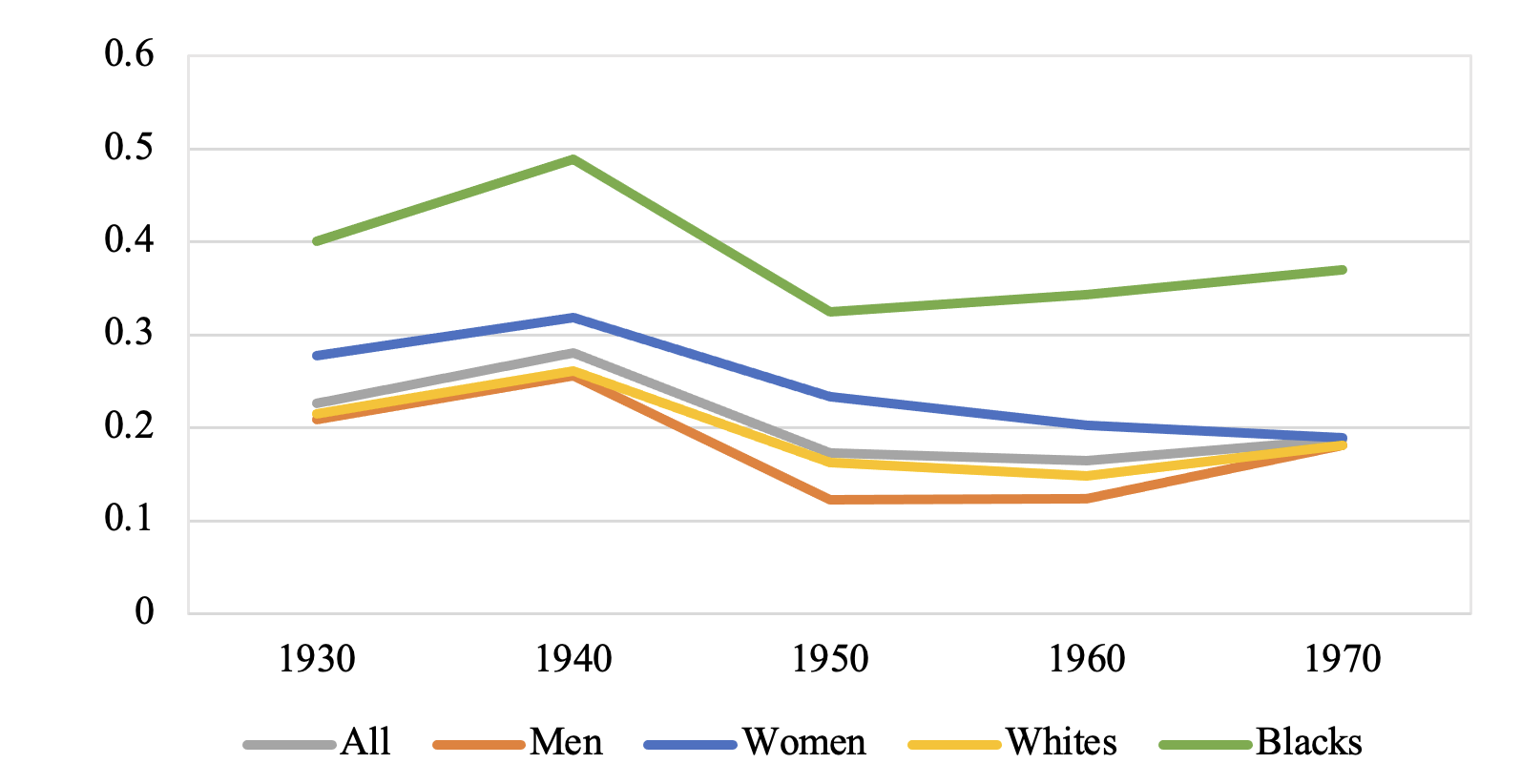

Figure 1 presents the share of late bloomers among all college graduates across birth cohorts overall and by demographic group. The share is around 20% on average, but it is not constant across birth cohorts: it decreased between the 1940 and 1960 birth cohorts but increased thereafter (see Figure 1). Moreover, both the level and its changes across cohorts differs substantially by demographic group. For example, between 32-49% of the Black college graduates are late bloomers, compared with 15-32% of the White college graduates.

Figure 1 Share of late bloomers among college graduates

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the decadal Census for 1960-2010 and ACS data for 2019. The figure shows the share of those who obtained a college degree after age 30 among those who obtained a college degree by age 50.

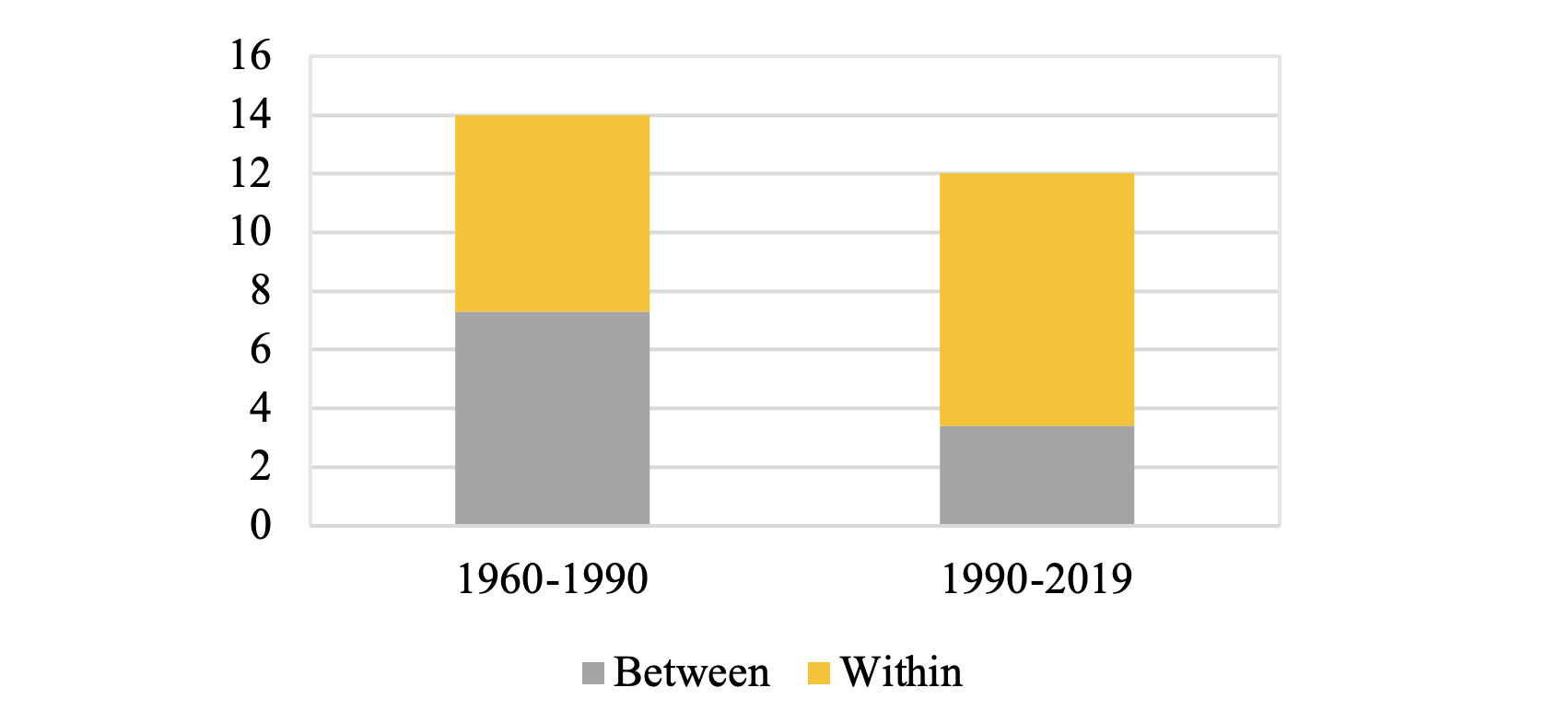

Given that late bloomers represent a substantial and varying share of college graduates, we examine how much of the aggregate increase in the share of college educated individuals can be explained by within-cohort increases (i.e. the late bloomers) and by between-cohort changes (i.e. successive cohorts getting more education).

Figure 2 Decomposition of aggregate college share change

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the decadal Census for 1960-2010 and ACS data for 2019. All changes are in percentage points. The two bars represent the change in the aggregate college share in the working age population from 1960 to 1990 and from 1990 to 2019, respectively. The within cohort component captures all changes in the college share of a given cohort after age 24 or earliest observed age.

Figure 2 reveals that around half of the increase between 1960 and 1990, and more than 70% of the increase between 1990 and 2019, is driven by within-cohort increases in the college share, i.e. by late bloomers. Similar decompositions done separately by gender and by race show that the role of late bloomers became more pronounced for all demographic groups but was larger for Black and for male graduates.

The gender and race college share gaps

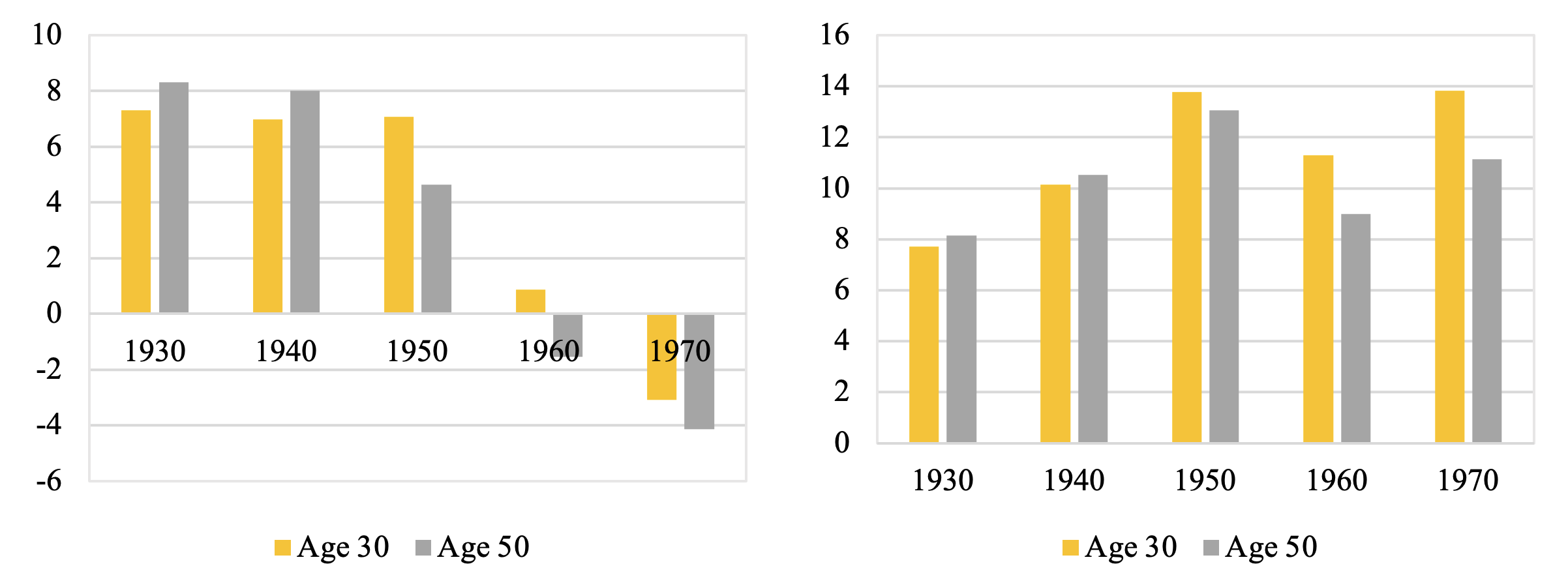

Figure 3 presents the college graduation gender and race gaps measured at age 30 and at age 50 for different birth cohorts. The left panel shows that the gender college gap decreased substantially across birth cohorts from 1930 to 1970. The narrowing measured at age 30 is 10.4 percentage points, while when measured at age 50 it is 12.4 percentage points. Hence, around a sixth of the narrowing of the gender college gap is driven by late bloomers. The right panel shows that the racial college gap has increased across the same birth cohorts. However, the widening of the gap is 6.1 percentage points at age 30 compared with only 3 percentage points at age 50. This implies that late bloomers contributed significantly to narrowing the racial gap, highlighting the importance of education later in life for the Black and Hispanic populations.

Figure 3 College share gaps at different ages

Notes: Authors’ calculations from the decadal Census for 1960-2010 and ACS data for 2019. The figure shows the differences in the share of college graduates between men and women (on the left) and between Whites and Blacks (on the right), measured at age 30 and at age 50 for different birth cohorts. All differences are in percentage points.

The returns to college education by age at graduation

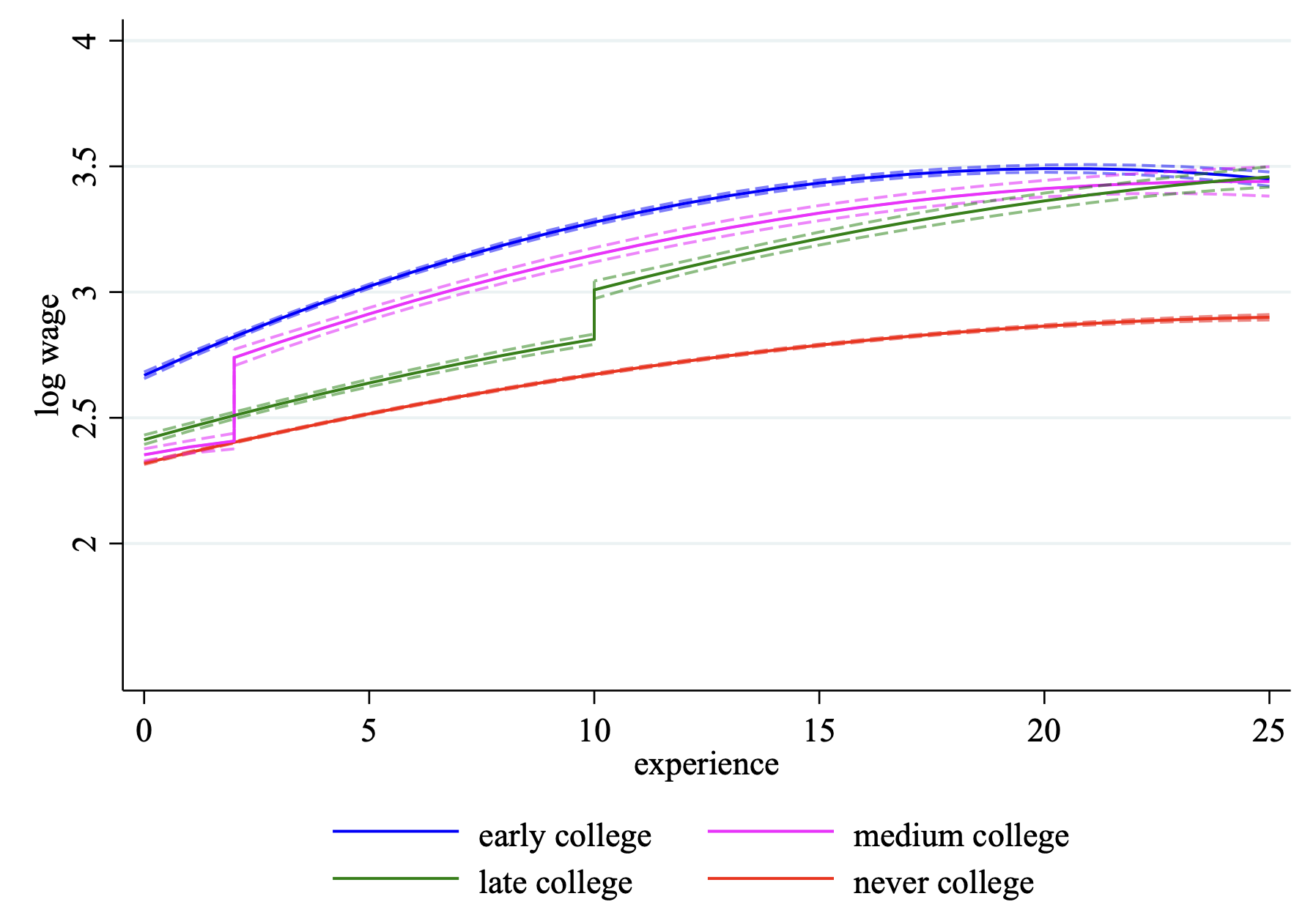

To understand whether the returns to college education differ by age at graduation, we use the NLSY data where we observe the age at college graduation and carry out a regression of (log) wage on experience, accounting separately for the experience accumulated before and after obtaining a college degree. We do so for the following four groups: (1) ‘early college’ (graduating by age 24); (2) ‘medium college’ (graduating between 25 and 29); (3) ‘late college’ (graduating at or after age 30); and (4) ‘never college’ (never obtained a college degree). We then contrast the estimated wage profiles for these groups, illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Wage-experience profiles by age at graduation

Notes: Authors’ calculations from NLSY79 data. Each curve shows the predicted wage path against experience for the representative individual from each group. The dashed lines show the 95% confidence intervals.

Not surprisingly, the ‘never college’ group has the lowest wage trajectory, while the ‘early college’ group has the highest trajectory. Both the ‘medium college’ and the ‘late college’ group enjoy a college premium upon graduating, but neither group manages to catch up with the ‘early college’ group. This graph makes it clear that bundling the ‘medium’ and ‘late’ college graduates with the ‘early’ college graduates when estimating cumulative wage returns to education will result in an underestimation of these returns. Overall, across all demographic groups, the underestimation is around 27%. The degree of underestimation varies from about 30% for men and 23% for women to 35% for Blacks and 40% for Hispanics.

Policy implications of late bloomers

Our findings have important implications, both for analysts and policymakers. First, to understand the evolution of the aggregate changes in college share, one must pay particular attention to the late bloomers. Second, the non-monotonical changes in the share of late bloomers across birth cohorts suggests that different forces are driving early and late college graduation. Moreover, the large differences across demographic groups in the share of late bloomers implies that these forces are likely to have differential effects on the various groups. Finally, increases in educational attainment are generally viewed as an advantage for innovation, economic competitiveness, and social mobility. This advocates strongly for a better awareness of how late bloomers contribute to innovation and economic competitiveness, and how much they benefit from social mobility. Policymakers should consider late bloomers when designing educational public policy.

References

Bárány, B and P Corblet (2023), “Late Bloomers? The Aggregate Implications of Getting Education Later in Life”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP18579.

Becker, G S (1994), Human Capital/ A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special reference to Education, The University of Chicago Press.

Bianchi, N (2014), “Access to higher education and the value of a university degree”, VoxEU.org, 29 December.

Bozzano, M and G Bertocchi (2020), “The education gender gap: from basic literacy to college major”, VoxEU.org, 5 October.

Keane, M P and K I Wolpin (1997), “The Career Decisions of Young Men”, Journal of Political Economy 105(3)

Lee, J (2002), “Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gap Trends: Reversing the Progress toward Equity?", Educational Researcher 31(1): 3-12.

Lee, D and K I Wolpin (2006), “Intersectional Labor Mobility and the Growth of the service Sector”, Econometrica 74(1).

Mincer, J A (1974), Schooling, Experience and Earnings, NBER.

Mogstad, M, K G Salavanes and MBhuller (2014), “Life cycle earnings, education premiums, and internal rates of return”, VoxEU.org, 22 September.

Rustichini, A, G Zanella and A Ichino (2022), “University education, intelligence, and disadvantage: policy lessons from the UK, 1960-2014”, VoxEU.org, 30 June,

White House (2023), Economic Report of the President, March.