The exploration of gender disparities in the economy is not only a matter of fairness and equality; it is also about addressing a crucial driver of economic growth. This subject consistently holds a prominent place in policy discussions and is a top priority on the agendas of academic researchers and policymakers, as evidenced by the recent awarding of the Nobel Prize in Economics to Claudia Goldin, who has devoted her work to this crucial topic (Bustan and Kuziemko 2023).

In a recent Bank of Italy report (Carta et al. 2023), we highlight the pressing issue of gender gaps in the Italian labour market. The report draws on research from the bank’s economists over the past three years and, by relating it with the existing literature, underscores the importance of addressing these disparities.

Why Italy is an interesting case study

Italy stands out in the EU as having one of the lowest female labour-force participation rates and the lowest employment rate. It also has the highest share of involuntary part-time employment among women. As a result, Italy holds large potential for economic growth by including more women in the labour market. The Bank of Italy’s estimates suggest that, other things equal, an increase of 10% in the labour force – which would see the participation rate of Italian women converge to the current EU level – would raise GDP by roughly the same amount in the long run. The effect would be even larger if one takes into account the potential extra gains from the consequent reallocation of talents in the economy (Hsieh et al. 2019).

Critical areas of intervention

Our report identifies three primary areas where gender gaps are most pronounced and warrant policy interventions.

1. Field of study choices and entry into the labour market

Gender gaps in earnings are already large and visible just one year after individuals complete their education. Based on detailed administrative data that link education careers with early labour market outcomes and earnings for seven cohorts of students, Bovini et al. (2023) show that while girls outperform boys at school, both in terms of the level of education achieved and school grades, they tend to select majors and fields of study associated with lower-paying jobs.

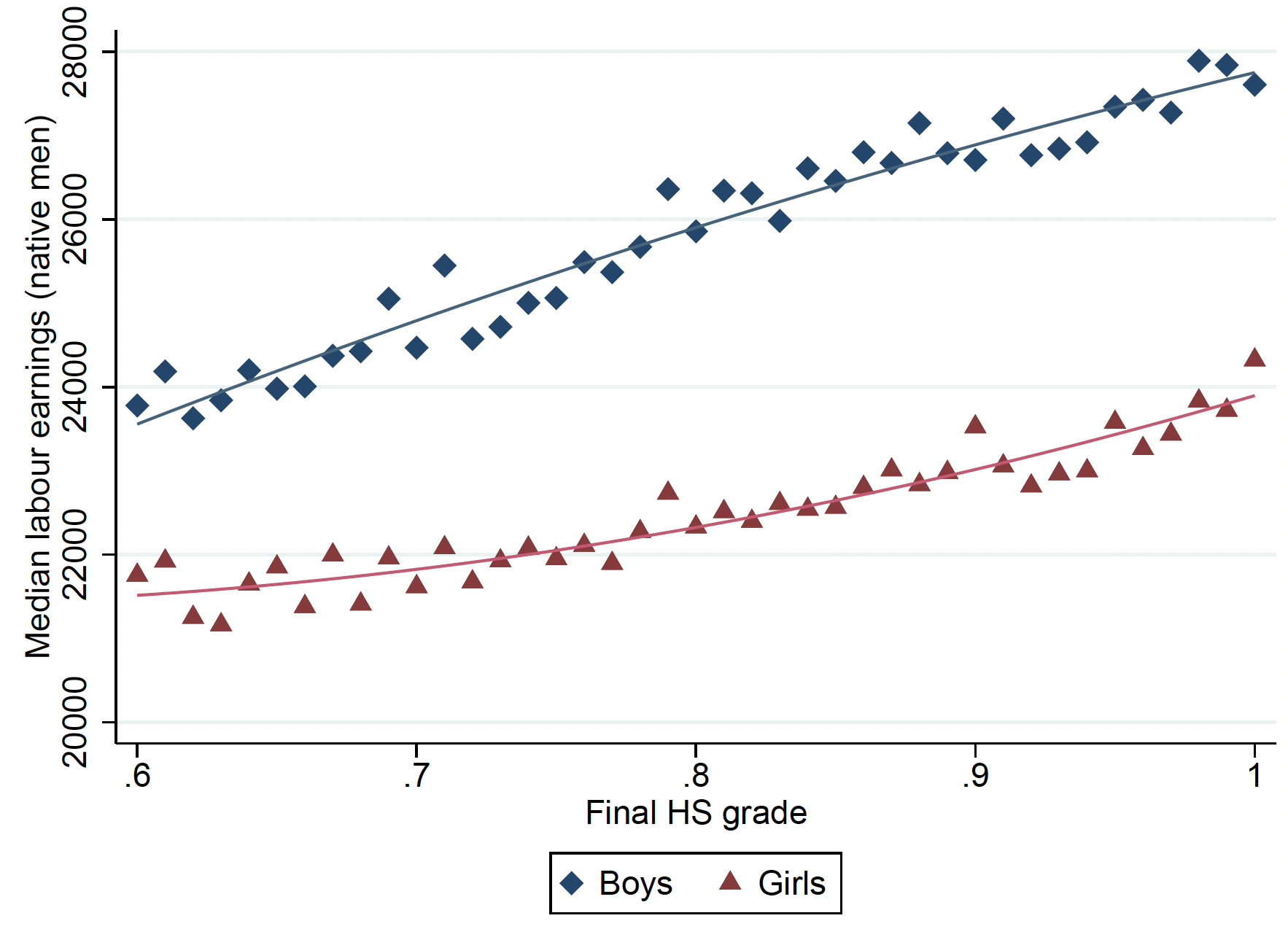

Figure 1 shows the average potential earnings (measured as the median earnings of native men who graduated from a given degree and then entered the labour market without pursuing any further education) of the degrees chosen by boys and girls, depending on their final high school grade. The figure shows that girls choose lower-paying university majors than boys and that this gap is larger for girls with higher final high school grades, i.e. the potential earnings of the degrees chosen by these girls are as low as those chosen by the worst-performing boys. This choice of university majors alone accounts for 60% of the gender pay gap observed at entry into the labour market among university graduates.

Figure 1 Potential labour market returns of university majors chosen by girls and boys, by final high school grade

Note: Potential labour market returns measured as the median labour earnings of male native students 5 years after graduation. Source: Bovini et al. (2023).

2. Maternity and work-life balance

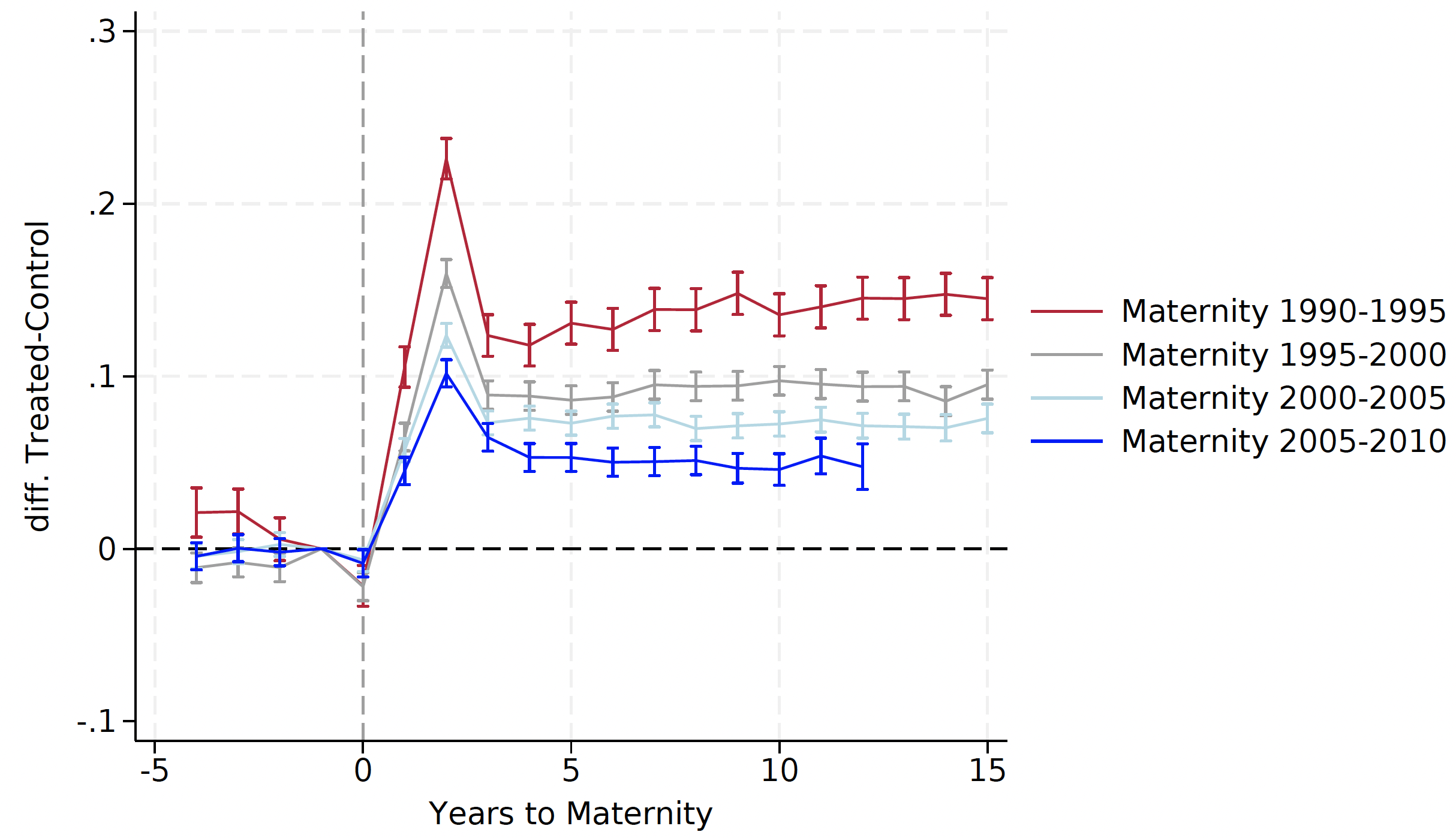

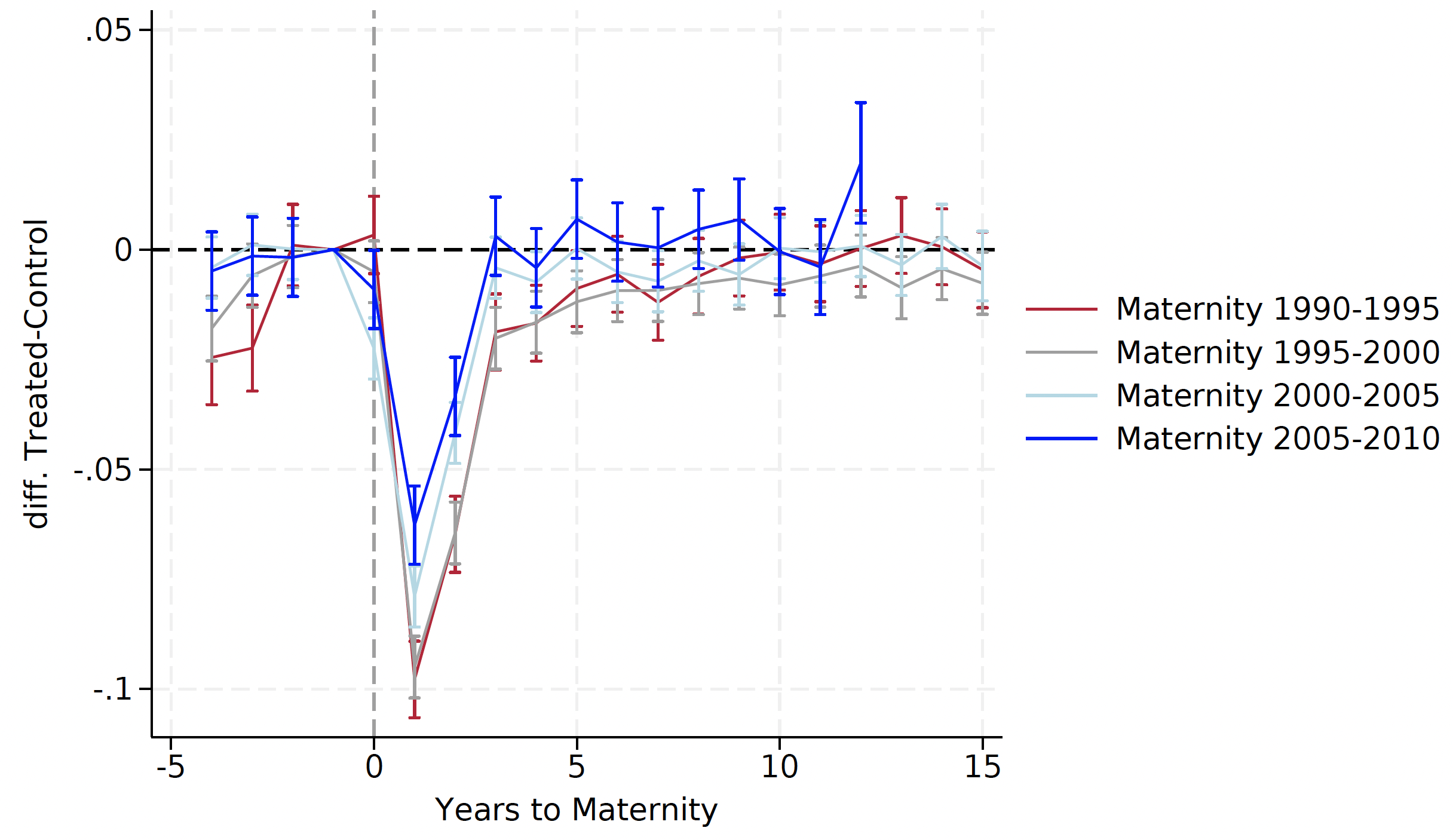

Gender gaps at entry into the labour market are persistent (Arellano-Bover et al. 2023) and widen when women have children. While, as in many other advanced economies, the relationship between fertility and female employment in Italy has become positive, reflecting improved work-life balance (Barbiellini Amidei et al. 2023), the probability for employed women to be non-employed in the two years following maternity doubles that of women without children (De Philippis and Lo Bello 2023). This gap persists over time and remains significant even 15 years after childbirth.

Additionally, for non-employed women, the likelihood of finding a job significantly decreases after the birth of a child and remains lower for at least five years. This contributes significantly to the existing gender employment gap: according to De Philippis and Lo Bello (2023) eliminating the existing child penalty among new mothers would increase the female employment rate by 6.5 percentage points by 2040 (i.e. 38% of the current gender employment gap). Removing the child penalties for both new and existing mothers would raise female employment by 14 percentage points by 2030, thus closing 85% of the existing gender gap.

Casarico and Lattanzio (2023a) furthermore show that women who remain employed after maternity earn 40% less than non-mothers even 15 years after giving birth, mostly because of a reduction in the number of working hours, attributed to the shift to part-time contracts.

Figure 2 Effects of giving birth on flows into and out of employment (EN and NE, respectively), over time

a) Employment to non-employment

b) Non-employment to employment

Source: De Philippis and Lo Bello (2023).

Culture surely plays an important role: child penalties for mothers are larger in regions with more traditional gender roles and cultural values. However, some shortcomings in the country’s family-friendly policies are also a crucial contributor to the formation and the amplification of such penalties. Specifically, in Italy there is very limited supply of childcare facilities for 0–2 year-olds; as a result, the Italian enrolment rate in childcare services for 0–2 year-olds is one of the lowest in Europe (about 26%, against 33% in the average of the EU).

Moreover, fathers in Italy make very limited use of parental leave. This phenomenon can be attributed not only to cultural factors but also to the less generous system of leaves for Italian fathers compared to other European countries. According to the OECD, in Italy, a mere 20.5% of the (full rate equivalent) leave is allocated to fathers; in the EU the average is over 30%.

Finally, the design of the tax-transfer system in Italy – which envisages for instance a tax credit for dependent spouses or some means-tested forms of income support – further discourages women’s employment as secondary earners in their families (Colonna and Marcassa 2015, Carta and Colonna 2023).

3. Slow career progression and under-representation in leadership positions

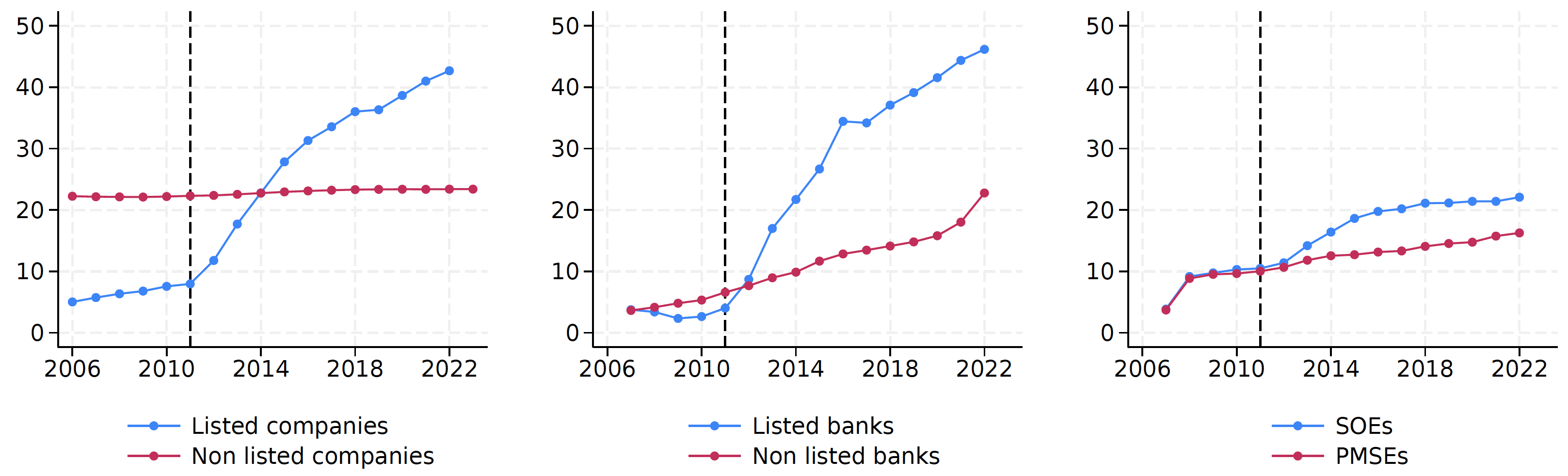

Women who remain in the labour market face also a significant wage gap with respect to men, which expands over the working life and is largest among top earners. Such differences in earnings reflect a severe under-representation of women in top professional positions (i.e. the glass ceiling). Figure 3 shows that the share of women sitting on the boards of Italian companies, banks, and publicly owned enterprises has increased significantly over the past decade but only for firms that were subject to binding gender quotas (introduced in 2011). Baltrunaite et al. (2022) and Del Prete et al. (2022) show that these changes in the boards brought along some marginal benefits in terms of firm performance. However, there is limited evidence that similar policies were effective in facilitating the career progressions of other women inside the firm (Bertrand et al. 2018, Maida and Weber 2022).

Figure 3 Share of women in administrative boards

Notes: The blue line refers to firms that were subject to binding gender quotas in boards from 2011, the red line to firms which were exempted. SOEs are state-owned enterprises, PMSEs are enterprises with public minority share of ownership.

Source: Carta et al. (2023).

The observed glass ceiling results from a combination of different factors: women end up working in less productive sectors – also as a result of their educational choices – and within these, in lower-paying firms. According to Casarico and Lattanzio (2023b), these differences explain about one-third of the average observed wage gap. Moreover, women tend to change jobs less often and obtain lower monetary benefits when doing so (Di Addario et al. 2023). Such inefficient allocation of female workers across firms would primarily derive from their own choices that aim at balancing monetary payoffs with other job characteristics, such as a lower distance from home or more flexible working hours.

Finally, women get promoted less often and are thus less likely to make it to the top hierarchies than their male co-workers. As highlighted in the existing literature, this reflects a lower propensity to bargain (Babcock and Laschevar 2003) and to reject non-remunerative tasks (Babcock et al. 2017). It also reflects differences in other non-cognitive traits such as self-confidence and aspirations. These attitudes are not innate but result from cultural norms which shape both the (female) workers’ behaviour and the reactions of the employers. As discussed in Baltrunaite et al. (2023), the presence of implicit biases and stereotypes heavily affects women’s careers.

Policy implications

Addressing the gender gaps in the Italian labour market requires a multifaceted approach:

- Combat cultural barriers and stereotypes. There is consensus that girls select less remunerative fields of study because of differences in preferences. Such preferences, however, are not innate but are heavily influenced by the cultural and social context they are exposed to (see also, among many, Bertrand 2020). Policies aimed at providing role models and raising awareness of implicit stereotypes can effectively encourage girls to pursue fields of study traditionally dominated by men.

- Improve family-friendly policies by increasing the supply of childcare facilities for young children. An important opportunity comes from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, which allocates approximately €2.7 billion to expand publicly provided childcare services for children aged 0–2. Moreover, it is important to promote the use of parental leave entitlements by fathers to rebalance the burden of domestic chores between partners. For instance, increasing the replacement rate for paternity leave compared with maternity leave, as in some Nordic countries, fosters the relative benefit for fathers to take parental leave when families have to choose which parent should take the leave

- Partly revise the tax and transfer system to reconcile the objectives of redistribution and equity with the need to limit distortions to labour supply, especially for women who tend to be the second earners in the family. In this respect, policies that benefit working mothers can be effective.

- Promote a family-friendly organisation of work, for instance by encouraging a more flexible work environment that relies less on a worker’s physical presence in the office or by offering benefits that include childcare services. Furthermore, fostering greater transparency regarding gender gaps within organisations may reduce the gender pay gap, by improving the allocation of women across firms and raising their bargaining power with the employer. The recent EU Directive (2023/970) to strengthen pay transparency could prove effective in this regard.

- Reinforce female presence in middle management, including through quotas, to help women within the organisation reach higher positions. Indeed, there is growing evidence showing the positive role of female team managers in supporting other women’s careers within the firm (Kunze and Miller 2017).

Authors' note: The opinions expressed are personal and do not in any way commit the Bank of Italy or the European System of Central Banks.

References

Arellano-Bover, J, N Bianchi, S Lattanzio, and M Paradisi (2023), “One cohort at a time: A new perspective on the declining gender pay gap”, Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (working papers), forthcoming.

Babcock, L, and S Laschevar (2003), Women don’t ask: Negotiation and the gender divide, Princeton University Press.

Babcock, L, M P Recalde, L Vesterlund, and L Weingart (2017), “Gender differences in accepting and receiving requests for tasks with low promotability”, American Economic Review 107(3): 714–47.

Baltrunaite A, A Casarico and L Rizzica (2022), “Women in economics: the role of gendered references at entry in the profession”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17474.

Baltrunaite, A, M Cannella, S Mocetti, and G Roma (2023), “Board composition and performance of state-owned enterprises: Quasi-experimental evidence”, Journal of Law, Economics and Organization.

Barbiellini Amidei, F, S Di Addario, M Gomellini, and P Piselli (2023), “Female labour force participation and fertility in Italian history”, Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (working papers), forthcoming.

Bertrand, M (2020), “Gender in the twenty-first century”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 110: 1–24.

Bertrand, M, S E Black, S Jensen, and A Lleras-Muney (2018), “Breaking the glass ceiling? The effect of board quotas on female labour market outcomes in Norway”, Review of Economic Studies 86(1): 191–239.

Bovini, G, M De Philippis, and L Rizzica (2023), “The origins of gender wage gaps: the role of school to work transition”, Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (working papers), forthcoming.

Boustan L, and I Kuziemko (2023), “Claudia Goldin, Nobel laureate: Gender gaps and the broader agenda on inequality”, VoxEU.org, 24 October.

Carta, F, and F Colonna (2023), “Minimum income and household labour supply”, Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (working papers), forthcoming.

Carta F, De Philippis M, Rizzica L, and Viviano E (2023), “Women, labour markets and economic growth”, Bank of Italy Workshops and Conferences 26.

Casarico, A, and S Lattanzio (2023a), “Behind the child penalty: Understanding what contributes to the labour market costs of motherhood”, Journal of Population Economics 36: 1489–511.

Casarico, A, and S Lattanzio (2023b), “What firms do: Gender inequality in linked employer-employee data”, Journal of Labor Economics, forthcoming.

Colonna, F and S Marcassa (2015), "Taxation and female labor supply in Italy. IZA", Journal of Labor Policy 4(1): 1–29.

De Philippis, M, and S Lo Bello (2023), “The ins and outs of the gender employment gap: Assessing the role of fertility”, Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (working papers), forthcoming.

Del Prete, S, G Papini, and M Tonello (2022), “Gender quotas, board diversity and spillover effects. Evidence from Italian banks”, Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (working papers) 1395.

Di Addario, S, P Kline, R Saggio, and M Sølvsten (2023), “It ain’t where you’re from, it’s where you’re at: Hiring origins, firm heterogeneity, and wages”, Journal of Econometrics 233(2): 340–74

Hsieh, C-T, E Hurst, C Jones, and P J Klenow (2019), “The allocation of talent and US economic growth”, Econometrica 87(5): 1439–74.

Kunze, A, and A Miller (2017), “Women helping women? Evidence from private sector data on workplace hierarchies”, Review of Economics and Statistics 99(5).