Central banks are fighting inflation by raising the interest rate. They implement this strategy by increasing the rate of remuneration of the deposits the banks hold at the central bank (bank reserves). As a result, with each interest rate hike, central banks increase the cash transfers to the banks. Since these bank reserves are now extremely high, mainly due to the large quantitative easing (QE) operations of the past, the transfers made by the central banks to the banks have reached extraordinary proportions. In the euro area, for example, these transfers now amount to €146 billion on a yearly basis. These are approaching the level of the total yearly spending by the EU (€168 billion). While the latter are the result of a painstaking political decision process and are disbursed only after satisfying long lists of conditions, the massive transfers to the banks by the central banks of the Eurosystem have not been preceded by any political discussion and are granted to the banks without any conditions. In the euro area, banks now obtain a rate of remuneration on risk-free and perfectly liquid assets of 4%. An extraordinary development.

Record profits of banks are made possible by record losses of central banks

The effect of this generosity of central banks is that euro area banks now make record profits (Financial Times 2023). The mirror image of this is that central banks make record losses, which will have to be borne by taxpayers (see Belhocine et al. 2023 for estimates of these losses). This is a remarkable development because banks tend to make losses during periods of interest rate increases. Today they make record profits made possible by transfers of the profits (and more) from the central banks.

In a series of contributions to VoxEU, we argued that it is possible to conduct effective anti-inflationary policies without the collateral damage of having to transfer all the profits (and more) of central banks to banks (De Grauwe and Ji 2023a, 2023b). We proposed a two-tier system of reserve requirements, which would transform part of the existing bank reserves into unremunerated minimum reserves; the other part in excess of these minimum reserves would continue to be remunerated at the prevailing deposit rate. The advantage of this system, we argued, is that the transfers could be reduced significantly, while the central banks could continue to use their current operating procedure.

The arguments we used in favour of a two-tier system of reserve requirements were mostly based on fairness considerations. We found out that quite a lot of economists, bankers, and central bankers are not very sensitive to fairness arguments. Therefore, we pursued our research and asked the question of whether the use of minimum reserve requirements could actually increase the effectiveness of monetary policies in fighting inflation.

This is an important question. The official view, as expressed by Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, in a letter to the European Parliament (Lagarde 2023), suggests that the remuneration of bank reserves is a key ingredient in the overall strategy of the central bank’s policy to fight inflation, without which this policy will be less effective. We want to show that the opposite holds, i.e. that the remuneration of bank reserves weakens the effectiveness of an interest rate hike to fight inflation.

The banks’ equity channel in the transmission of monetary policy

In order to show this, we first turn to the theory. There is a large economic literature on the equity channel of bank lending which is relevant here. This can be described as follows. When the bank’s capital (equity) declines banks will have an incentive to reduce lending. There are essentially two reasons for this. One is a balance sheet effect. A lower equity means that the bank may not satisfy the minimum capital requirements imposed by regulators. The bank will then have to reduce the supply of loans. The second reason is that with lower equity, the cost of funding bank loans tends to increase, thereby leading to fewer incentives for banks to lend. Thus, a decline in the value of banks’ equity leads to less bank lending. Conversely, an increase in the value of equity stimulates banks to lend more (Gambacorta and Shin 2016, Van den Heuvel 2002, Diamond and Rajan 2000). This theory has been subjected to many empirical tests confirming its importance (Boucinha, et al. 2017, Girotti and Horny 2020).

This theory is also important for the transmission of monetary policies. When the central bank raises the interest rate this will have a direct negative effect on bank loans that have become more expensive. It will also have an indirect effect through the equity channel: the higher interest rate tends to reduce the value of the banks’ equity (because it lowers the collateral value of the banks’ loans). In addition, a rate hike typically leads to a recession which tends to increase the size of non-performing loans. This also has a negative effect on the value of equity of banks. This equity effect in turn will induce the banks to lower the supply of loans. Thus, the equity channel tends to amplify the direct effect of the increased interest rate on bank loans. In so doing it strengthens the transmission process of interest rate hikes in the fight against inflation.

It can now be seen that the remuneration of bank reserves weakens this transmission process. When today the central banks raise the interest rate and as a result increase the remuneration of reserves, they induce a positive equity effect, and in so doing they give incentives to banks to extend more loans (ceteris paribus). Put differently, the expected negative effect of a rate hike on loans is (partly) offset by the positive equity effect on bank loans when bank reserves are remunerated. The transmission mechanism is made less effective, i.e. increases in the policy rate have a lower effect on the loan supply and ultimately on inflation when central banks remunerate bank reserves.

Empirical evidence of the equity channel

We tested this hypothesis by applying econometric methods using euro area country-level monthly data from September 2022 to August 2023. We regressed the percentage changes in bank loans to non-financial corporations on the levels of bank reserves (as a percent of GDP), the change in the remuneration of these bank reserves during the recent period of interest rate hikes, and a number of control variables. We did the same for bank loans to households.

In De Grauwe and Ji (2023c), we report four major findings:

- The policy rate has the expected negative effects on the growth of loans to non-financial corporations and households. This effect of the policy rate measures the rate hike effect without remuneration of bank reserves. It can be called the direct effect.

- The level of reserves has a positive and significant effect on the growth of bank loans.

- Equity effect: There is a positive and significant association between the change in the remuneration of bank reserves and the growth of bank loans. Thus, when bank reserves are high in a country, bank loans in that country will decline less when due to a hike in the policy rate the remuneration of bank reserves increases. The ensuing positive equity effect gives banks an incentive to increase the supply of loans. All this weakens the transmission of monetary policies in the fight against inflation.

- There is significant difference in the equity effect between the high-reserve (top-50%) and the low-reserve (bottom 50%) countries. We find that in countries with bank reserve levels above the median (mostly countries from the Northern euro area i.e. Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands), the equity effect of remuneration is strong and significant. This is less the case in the subsample of countries with relatively low levels of reserves. This is in a way not surprising. In countries with low levels of reserves the equity effect on loans is weak as bank reserves (and their changes) have a weak impact on the net worth of the banks. Our results are in line with the recent findings of Fricke et al. (2023) who use very detailed bank-level data for the euro area.

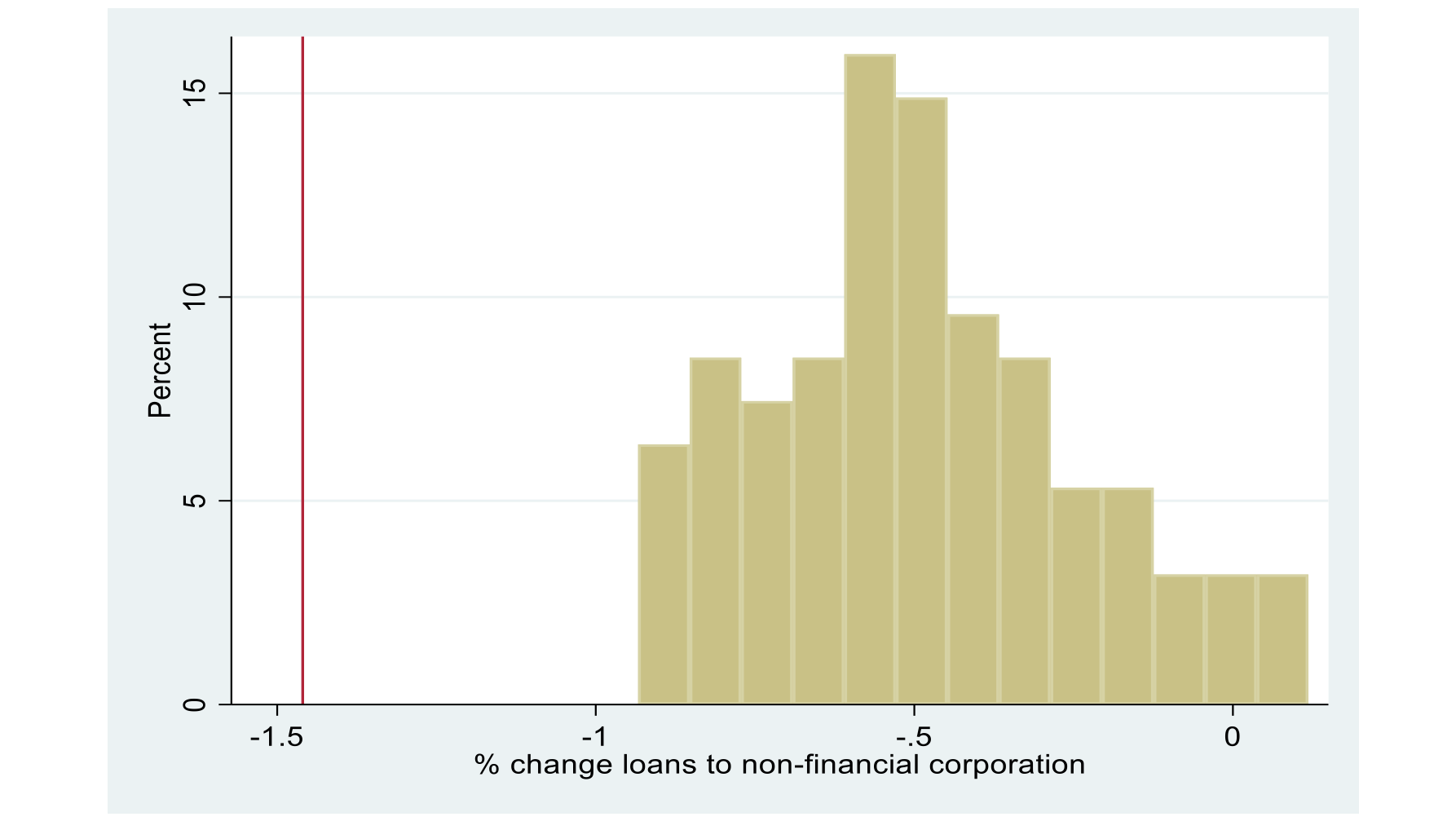

Our empirical finding confirms that the current regime of remuneration of bank reserves reduces the effectiveness of the transmission of monetary policies. Figure 1 shows how strong this reduction is. We concentrate on the high-reserve countries and compute the equity effects for different levels of bank reserves (as a percent of GDP) in the sample. Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of the total effects (direct and equity) of a 1% interest rate hike on the supply of loans to non-financial corporations. We can compare these with the direct effect (the effect without remuneration), represented by the vertical red line (-1.46%). We find that the total effects of a rate hike remain negative for most observations but that they are significantly reduced (in absolute value) compared to the effect without remuneration. Thus, by strengthening the equity position of reserve-rich banks, the remuneration of bank reserves gives them incentives to increase the loan supply thereby weakening the transmission of monetary policy.

Figure 1 Total effects of a 1% policy rate hike on the percent change in loans to non-financial corporations

High-reserve (top 50% subsample, excluding Cyprus and Luxembourg)

Source: De Grauwe and Ji (2023c)

Note: the vertical axis shows the frequency distribution of the total effects of a rate hike as a function of the size of bank reserves (% of GDP) of the different countries

A two-tier system of reserve requirements reduces the equity effect

It follows from our empirical evidence that by imposing unremunerated minimum reserves the central bank reduces the positive equity effect of a rate hike on bank loans. The two-tier system that we proposed earlier (De Grauwe and Ji 2023a), whereby part of the bank reserves would be converted into unremunerated minimum reserves (allowing for remuneration of excess reserves), is a tool that reduces the equity effect and enhances the effectiveness of the transmission of monetary policies. Thus, the use of unremunerated minimum reserve requirements together with the interest rate instrument makes the fight against inflation more effective. It is interesting to note that the Swiss National Bank followed this logic recently and lowered the remuneration on required reserves (Swiss National Bank 2023).

One may object here that by reducing banks’ profits and their net worth, the introduction of unremunerated reserve requirements raises potential financial stability issues. In the present context of record high profits, due to a large extent to the remuneration policy of bank reserves, our proposal would make the banks’ record high profits just normal profits (Standard & Poor’s 2023).

In a way, it should not come as a surprise that the use of minimum reserve requirements makes monetary policy more effective in the fight against inflation. The use of two instruments (the policy rate and minimum reserve requirements) to fight inflation is likely to be more effective than using just one instrument (the policy rate). Our proposal of a two-tier system of minimum reserve requirements therefore reconciles fairness and effectiveness.

References

Belhocine, N, A Bahtia and J Frie (2023), “Raising Rates with a Large Balance Sheet, The Eurosystem’s Net Income and its Fiscal Implications”, IMF Working Paper, July.

Boucinha, M, S Holton and A Tiseno (2017), “Bank equity valuations and credit supply”, ECB Working Paper.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2023a), “Monetary Policies with fewer subisidies for banks: A two-tier system of reserve requirements”, VoxEU.org, 13 March.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2023b), “Monetary Policies without Giveaways to Banks”, CEPR Disussion Paper 18103.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2023c), “Fighting inflation more effectively without transferring central banks’ profits to banks”, CESifo Discussion Paper.

Diamond, D W and R G Rajan (2000), “A Theory of Bank Capital”, Journal of Finance 55(6): 431-65.

Fricke, D, S Greppmair and K Paludkiewicz (2023), “Excess Reserves and Monetary Policy Tightening”, Discussion Paper, Bundesbank, Frankfurt.

Financial Times (2023), “European Banks to reveal profit boost form higher rates”, 23 October.

Gambacorta, L and H S Shin (2016), "Why bank capital matters for monetary policy", BIS Working Papers 558.

Girotti, M and G Horny (2020), “Bank Equity Value and Loan Supply”, Banque de France Working Paper No. 767.

Lagarde, C (2023), “Letter to Members of the European Parliament”, European Central Bank, 22 September.

Standard & Poor’s (2023), “Eurozone Banks: Higher Reserve Requirements Would Dent Profits and Liquidity.”

Swiss National Bank (2023), “Press Release”, 30 October.

Van den Heuvel, S (2002), “Does bank capital matter for monetary transmission?”, Economic Policy Review 8(1).