On 1 February 2024, the EU finished another Summit that had Ukraine, and its future relations with the EU, as one of its main topics. This meeting was in effect a continuation of the enlargement-related discussions of the previous Summit in December 2023, and had implications for other countries aiming for EU membership amidst the geopolitical storms battering the European continent, namely, on the financing side of this complex process.

Moldova and Ukraine applied for EU membership in February 2022. After a favourable opinion by the European Commission, and approval by the European Council, they were granted EU candidate status in June 2022 and, in December 2023, the European Council decided to open negotiations for EU accession with both. Georgia, on the other hand, applied for EU membership in March 2022 and was granted candidate status in December 2023, on the understanding that it takes the relevant steps as set out in a Commission recommendation (therefore, accession negotiations have not yet been opened with that country).

For both Moldova and Ukraine, the process so far has been speedy (by EU enlargement standards), and historically unique as it involves one country that is under an open military conflict with a belligerent Russia and has part of its territory occupied by military forces of that country (Kappner et al. 2022), and another that is under severe and continued pressure (albeit short of open military conflict) from that same belligerent power. Therefore, beyond the traditional promise of economic development normally associated with EU membership (often referred to as an economic ‘convergence machine’; see Ridao-Cano and Bodewig 2018), it also carries for those countries the promise of shelter from those pressures, and even of national survival (given the ‘mutual defence’ clause in Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union, which states that if an EU Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States have an obligation to aid and assist it by all means in their power).

Previous enlargements

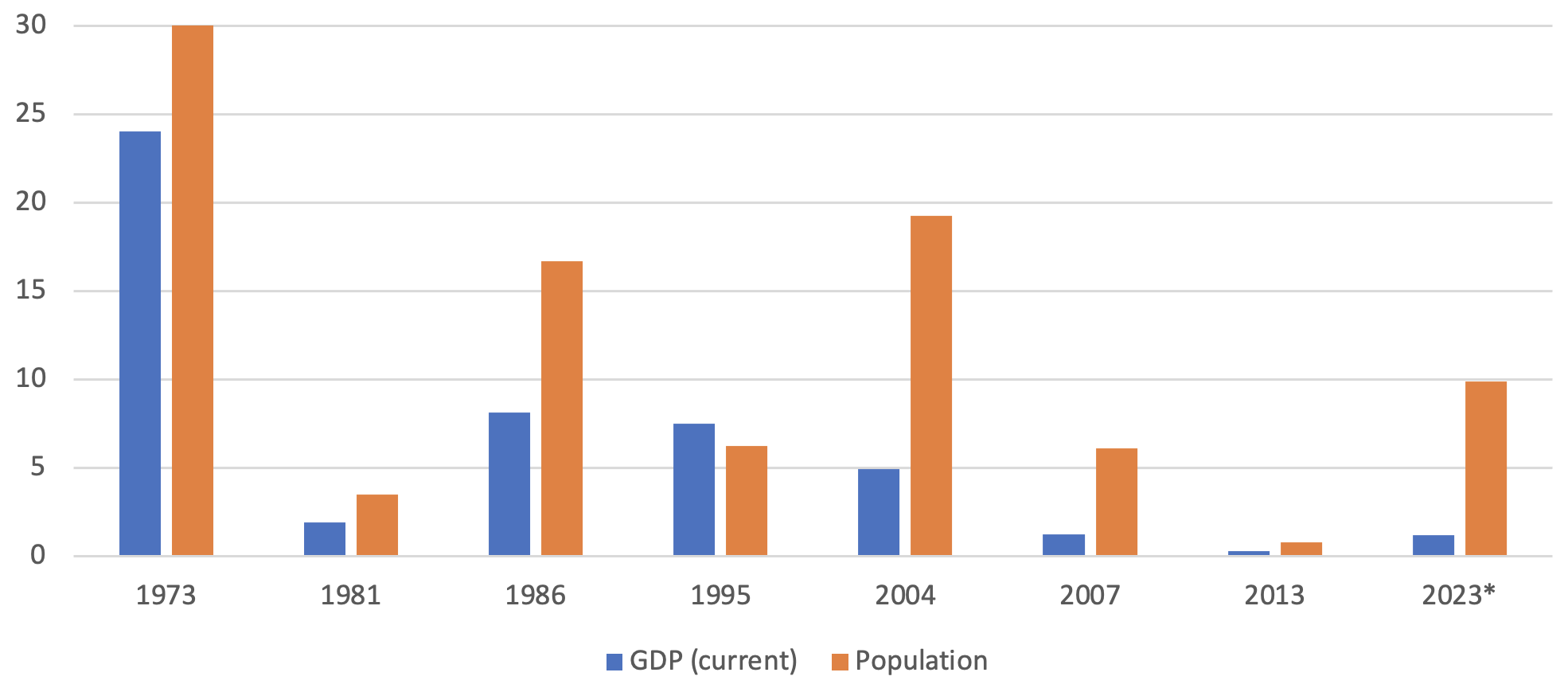

‘Enlargement’ is the expression used for the situation in which new countries ‘accede’ to the EU, i.e. become an EU Member State. The EU has so far had seven enlargements: the first took place in 1973, and led to the accession of Denmark, Ireland, and the UK (the UK would leave the EU in 2020); in 1981 Greece became a member; in 1986 it was Portugal and Spain’s turn; in 1995 Austria, Finland, and Sweden entered the EU; the fifth enlargement happened in 2004 and saw ten countries – Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia – join the EU at the same time; in 2007 Bulgaria and Romania became members; and Croatia joined in 2013. The scale of each of these enlargements as a share of the GDP and of the population of the EU is shown in Figure 1 (the shares are a ratio of the EU totals for the year before accession), as is the potential accession of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. Importantly, the EU as a whole and its Member States – old and new – benefit from all those enlargements (e.g. European Commission 2009).

As one can see in Figure 1, the largest enlargement both as a share of the EU’s GDP and population was actually the first one in 1973, which reflects the small number of initial EU Member States and the large relative importance of the UK: the EU’s population increased by almost quarter, and its GDP by 30%. The second largest, GDP-wise, was the joint Iberian accession of Portugal and Spain in 1986, which increased the EU’s previous GDP by around 8%; in terms of population, the 2004 ‘big bang’ enlargement towards Central Europe, which increased the EU’s population by around 19%, was the second largest. An enlargement to Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine would be the fourth largest in terms of population, and the sixth largest in terms of GDP.

Figure 1 How large where enlargements in relation to the EU?

Source: Author, using IMF and World Bank data.

Note: *Data for 2023 uses the IMF estimated GDPs for 2023 and the 2022 populations.

Enlargements directly affect the governance mechanisms of the EU, as around 20% of the votes on the European Council (the main decision-making body of the EU) follow an unanimity process, where any single Member State can block decisions. Unanimity is used in some key policy areas, from security and defence to taxation and EU finances, and enlargement itself. However, the population size of new EU Member States also matters for EU governance in two ways: via voting on the European Council and via representation in the European Parliament (which shares with the European Council the power to adopt and amend legislative proposals, and also approves the EU budget). About 80% of votes in the European Council use a ‘qualified majority voting’ (QMV) process, where a qualified majority is reached if two conditions are simultaneously met: (1) 55% of Member States vote in favour, and (2) the proposal is supported by Member States representing at least 65% of the total EU population. As for the European Parliament, its seats (capped at a maximum of 750) are allocated using as a reference the population of the EU Member State, but under a ‘degressive proportionality’ scheme that gives more seats per capita go to less populous Member States.

The GDP of new EU Member States also matters, not necessarily or only in and of itself, but rather in terms of the EU’s financing and redistribution mechanisms: the EU has many and significant mechanisms of unilateral transfers, of a sectoral nature (think of the Common Agricultural Policy’) and of a ‘cohesion’ nature (which is EU lingo for transfers to Member States and regions with, roughly, a GDP per capita

below the EU average, to help them converge to this average). Those transfers are mainly financed by a subset of EU Member States that are net payers to the EU budget (as all EU Member States do pay towards the common EU budget). The upshot of this is that of the enlargement waves, only the first and the fourth ones – in 1973 and 1995 – invovled net payers,

while all the other enlargements involved net recipient countries. As the numerical balance now favours net recipient Member States, the transfers component of the EU budget has increased. Also, enlargement towards Member States with lower GDP per capita than existing EU Member States effectively implies that current net recipients will either receive relatively less transfers or even become net payers;

this outcome is enhanced if the new Member State has a relatively large agricultural sector.

There are several indicative estimates of the potential financial costs of a next enlargement wave, mostly concentrating on Ukraine (e.g. Emerson 2023, Lindner et al. 2023). These estimates, fluctuating between €10–20 billion net per year

(with CAP-related costs for Ukraine being a major item), are highly uncertain, but suggest seemingly manageable figures, even before any considerations about likely adjustments to those policies. However, these estimates abstain from including the amounts that will be necessary for the prolonged post-war reconstruction needs of Ukraine, which, although also highly uncertainty, are likely to be very significant (World Bank et al. 2023), which is acknowledged by the proposed ‘Ukraine Facility’. This country-specific facility would pool the EU’s reconstruction and accession-related budget support for Ukraine into one single instrument, and would be structured into three pillars:

- Pillar I: The government of Ukraine will prepare a ‘Ukraine Plan', setting out its intentions for the recovery, reconstruction, and modernisation of the country and the reforms it plans to undertake as part of its EU accession process. Financial support in the form of grants and loans to the state of Ukraine would be provided based on the implementation of the Ukraine Plan, which would be underpinned by a set of conditionalities and a timeline for disbursements.

- Pillar II: Under the Ukraine Investment Framework, the EU will provide support in the form of budgetary guarantees and a blend of grants and loans from public and private institutions to cover the risks of loans and other forms of funding.

- Pillar III: Technical assistance and other supporting measures helping Ukraine align with EU laws and carrying out accession-related structural reforms.

The initial European Commission proposal was for a €50 billion facility, €17 billion in grants, and €33 billion in loans, and that was the main leftover from the December 2023 Summit. Beyond aiming to a medium-term stable funding mechanism to Ukraine, it also aims to partially separate the funding of Ukraine-related expenditures from those related to other EU accession countries. This was the ‘unresolved business’ from December 2023.

So, onwards to the next enlargements?

The period elapsed since the last enlargements in 2013 is the longest one since enlargements began in 1973. The underlying process is in itself usually a long one, with lags between application and accession easily a decade long (for instant, Portugal applied for EU membership in 1977, while the ten Central European countries that acceded to the EU between 2004 and 2007 lodged their applications between 1994 and 1996).

That is because the process is rather complex. The accession negotiations prepare the candidate for eventual membership, focusing on the adoption of the whole body of EU laws and regulations (the ‘Acquis communautaire’, currently estimated at 110,000 pages) and the related implementation of all the needed judicial, administrative, and economic reforms.

Only when negotiations on all policy areas are completed, and the EU itself is prepared for enlargement in terms of ‘absorption capacity’ (an ill-defined concept), is an accession treaty prepared. This document still needs the European Parliament’s consent and the European Council’s unanimous approval before all EU Member States and the candidate country can sign it. Only then doe the candidate become an EU Member State.

So, the journey ahead for these countries is likely to be complex and long (for how long it has already been, see Vinhas de Souza et al. 2006), with inevitable broader discussions about the governance of an eventually even larger and more heterogenous EU at some point in the near future. That said, the immediate hurdle left from the EU Council Summit of December 2023 was addressed by the decisions of the Special Summit of 1 February 2024 (European Council 2024), namely, the 2024–2027 financing of the (pre-accession) reconstruction of Ukraine via the Ukraine Facility, integrated into discussions of the mid-term review of the EU budget (known as the Multiannual Financial Framework, or MFF). This outcome has direct – and positive – implications for the other candidate countries. And the geostrategic imperative for another EU enlargement could not be clearer.

So, this journey will continue. Fare thee well.

Author’s note: This column does not necessarily reflect the view of any organisation to which the author is or was linked.

References

Emerson, M (2023), “The Potential Impact of Ukrainian Accession on the EU’s Budget, and the Importance of Control Valves”, International Centre for Defence and Security, Tallinn.

European Commission (2009), “Five years of an enlarged EU: economic achievements and challenges”, Brussels.

European Council (2024), “European Council conclusions”, Brussels, 1 February.

Kappner, K, N Szumilo and M Constantinescu (2022), “Estimating the short-term impact of war on economic activity in Ukraine”, VoxEU.org, 21 June.

Lindner, J, T Nguyen and R Hansum (2023), “What does it cost? Financial implications of the next enlargement”, Jacques Delors Centre, Hertie School, Berlin.

Ridao-Cano, C and C Bodewig (2018), “Growing united: upgrading Europe's convergence machine”, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Vinhas de Souza, L, R Schweickert, V Movchan, O Bilan and I Burakovsky (2006), “Now So Near, and Yet Still So Far: Relations Between Ukraine and the European Union”, in L Vinhas de Souza and O Havrylyshyn (eds), Return to Growth in CIS Countries, Springer.

World Bank, Government of Ukraine, European Union, and United Nations (2023), “Ukraine Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment: February 2022 - February 2023”, Washington, DC.