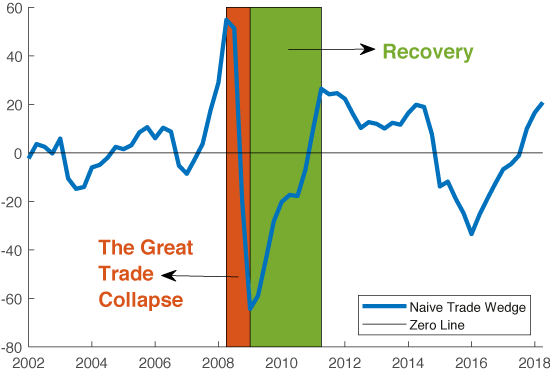

The reduction in international trade was larger than the reduction in economic activity during the Global Crisis. This observation has been accepted as extraordinary, because its magnitude has been far larger than in previous downturns, even after controlling for relative prices of imports. This is shown in Figure 1 for the US and has come to be known as the Great Trade Collapse.

Figure 1 Naïve trade wedge

Source: Yilmazkuday (2019).

Note: The naïve trade wedge in Figure 1 is defined as the deviation from the implications of a simple demand-side model, where the US quarterly data on total consumption versus imports as well as the corresponding price indices are considered with an Armington elasticity of 5. All data are in logs, seasonally adjusted, and detrended using the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

Competing explanations in the literature

Since the relationship between trade and economic activity is one to one in standard trade models,1 this collapse in trade has attracted attention in the recent literature. Its causes have been investigated extensively, not only because the decline in trade flows relative to overall economic activity was surprisingly high, but also because it has important implications for optimal policy response. For example, Alessandria et al. (2010a and 2010b) have connected the Global Trade Collapse to the dynamics of inventories and compositional differences between traded goods and GDP. Bems et al. (2010), Levchenko et al. (2010), Bussiere et al. (2013), and Behrens et al. (2013) made the connection to the composition of demand. Eaton et al. (2016) investigated investment efficiency, whereas Amiti and Weinstein (2011), Ahn et al. (2011), Feenstra et al. (2014), and Zymek (2012) focused on trade finance and credit. In contrast, Crowley and Luo (2011) linked the Global Trade Collapse to declining aggregate demand, and Baldwin and Evenett (2008), and Bown and Crowley (2013) to higher trade costs due to protectionist policies. Chor and Manova (2012) and Paravisini et al. (2014) focused on overall (rather than trade) credit and finance market indicators in the source country.

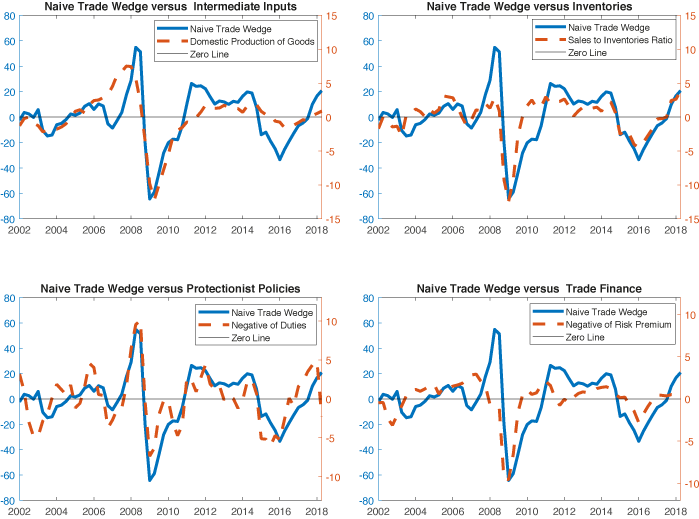

Since most of these papers have competing stories, they have sometimes had conflicting results. For example, Levchenko et al. (2010) deny the contributions of inventories and trade finance, whereas Crowley and Luo (2011) and Behrens et al. (2013) deny the contribution of higher trade costs. Alessandria et al. (2010a) connect the results in Eaton et al. (2016) to the lack of a dynamic inventory mechanism, and so forth. It is implied that multiple stories may have contributed to the Great Trade Collapse at the same time. Evidence for such a claim is given in Figure 2, where the naïve trade wedge from Figure 1 is visually connected to alternative stories in the literature based on US data.

Figure 2 Naïve trade wedge versus competing stories

Source: Yilmazkuday (2019).

Notes: In the figure, domestic production of goods is used as a measure of intermediate input usage, sales to inventories ratio is used as a measure of inventories, the negative value of effective tariffs/duties in ad-valorem terms is used to measure protectionist policies, and the negative value of risk premium faced by corporate bonds is used as a measure of trade finance. All data are in logs, seasonally adjusted, and detrended by using the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

Evaluating the competing stories

As is evident in Figure 2, the naïve trade wedge is highly correlated with US data representing alternative stories in the literature. But what is the contribution of each story? Are these stories complements or substitutes to each other? Based on the literature introduced so far, answering these questions requires a structural estimation of a dynamic trade model with ingredients including intermediate-input trade, inventories, protectionist policies, trade finance, and financial interactions between countries.

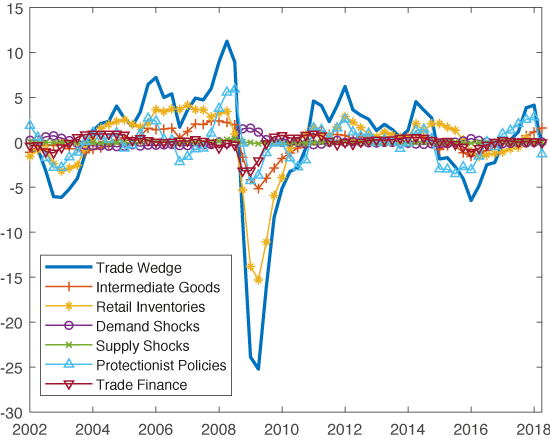

My recent work (Yilmazkuday 2019) introduces such a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) trade model to investigate the contribution of competing stories in the literature to the Great Trade Collapse.2 The parameters of this model are estimated by state-of-the-art Bayesian techniques using 18 series of quarterly data from the US, including durable and nondurable imports, durable and nondurable production, services versus overall consumption, prices, inventories, protectionist policies (duties), trade finance (risk premium faced by corporate bonds), and wages. The estimated model is used to introduce a new trade wedge, this time based on the DSGE model, where the contribution of each competing story is evaluated, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Decomposition of the trade wedge based on the DSGE model

Source: Yilmazkuday (2019).

Notes: This new trade wedge is calculated by controlling for implications of the DSGE model other than the stories in the literature that have contributed to the Great Trade Collapse. All data are in logs, seasonally adjusted, and detrended using the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

When overall US imports are considered, the results in Figure 3 show that retail inventories have contributed the most to the Global Trade Collapse and the corresponding recovery, followed by protectionist policies, intermediate-input trade, and trade finance. Specifically, the collapse of overall US imports is explained by:

- retail inventories (47%),

- protectionist policies (28%),

- intermediate inputs (21%),

- trade finance (5%),

- productivity shocks (2%), and

- demand shocks (–3%).

The corresponding recovery is explained by

- retail inventories (57%),

- intermediate inputs (20%),

- protectionist policies (18%),

- trade finance (10%),

- productivity shocks (0%), and

- demand shocks (–5 %).

To address concerns regarding compositional effects, I find similar for durable and nondurable imports of the US as well, again based on the DSGE model. While retail inventories have been mostly responsible for the collapse and recovery of durable imports, as shown in Figure 4, it has been intermediate-input trade that has contributed the most to the collapse and recovery of nondurable imports, as shown in Figure 5. Both durable and nondurable imports have been significantly affected by protectionist policies, while the contribution of trade finance has been higher for durable imports.

Figure 4 Decomposition of the durable wedge based on the DSGE model

Source: Yilmazkuday (2019).

Notes: The durable and nondurable wedges in Figures 4-5 are calculated by controlling for implications of the DSGE model other than the stories in the literature that have contributed to Great Trade Collapse. All data are in logs, seasonally adjusted, and detrended using the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

Figure 5 Decomposition of the nondurable wedge based on the DSGE model

Source: Yilmazkuday (2019).

Notes: The durable and nondurable wedges in Figures 4-5 are calculated by controlling for implications of the DSGE model other than the stories in the literature that have contributed to Great Trade Collapse. All data are in logs, seasonally adjusted, and detrended by using the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

The results presented suggest a clear picture: retail inventories are able to explain about half of both the collapse and the recovery in US imports. This analysis not only helps to understand the effects of the Global Crisis on trade, but can also be used to guide policymakers in future economic turbulence.

References

Ahn, J, M Amiti and D E Weinstein (2011), “Trade finance and the great trade collapse”, American Economic Review, 101(3): 298-302.

Alessandria, G, J P Kaboski and V Midrigan (2010a), “The great trade collapse of 2008-09: An inventory adjustment?”, IMF Economic Review 58(2): 254-294.

Alessandria, G, J P Kaboski and V Midrigan (2010b), “Inventories, lumpy trade, and large devaluations”, American Economic Review 100(5): 2304-39.

Amiti, M and D E Weinstein (2011), “Exports and financial shocks”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(4): 1841-1877.

Baldwin, R and S J Evenett (2008), “The crisis and protectionism: Steps world leaders should take”, VoxEU. org.

Behrens, K, G Corcos and G Mion (2013), “Trade crisis? What trade crisis?”, Review of economics and statistics 95(2): 702-709.

Bems, R, R C Johnson and K-M Yi (2010), “Demand spillovers and the collapse of trade in the global recession”, IMF Economic Review 58(2): 295-326.

Bown, C P and M A Crowley (2013), “Import protection, business cycles, and exchange rates: Evidence from the great recession”, Journal of International Economics 1(90): 50-64.

Bussière, M, G Callegari, F Ghironi, G Sestieri and N Yamano (2013), “Estimating trade elasticities: Demand composition and the trade collapse of 2008-2009”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5(3): 118-51.

Chor, D and K Manova (2012), “Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis”, Journal of International Economics 87(1): 117-133.

Crowley, M and X Luo (2011), “Understanding the Great Trade Collapse of 2008-09 and the subsequent trade recovery”, Economic Perspectives 35(2): 44-68.

Eaton, J, S Kortum, B Neiman and J Romalis (2016), “Trade and the global recession”, American Economic Review 106(11): 3401-38.

Feenstra, R C, Z Li and M Yu (2014), “Exports and credit constraints under incomplete information: Theory and evidence from China”, Review of Economics and Statistics 96(4): 729-744.

Levchenko, A A, L T Lewis and L L Tesar (2010), “The collapse of international trade during the 2008-09 crisis: In search of the smoking gun”, IMF Economic Review 58(2): 214-253.

Paravisini, D, V Rappoport, P Schnabl and D Wolfenzon (2014), “Dissecting the effect of credit supply on trade: Evidence from matched credit-export data”, The Review of Economic Studies 82(1): 333-359.

Yilmazkuday, H (2019), “The Great Trade Collapse: An evaluation of competing stories”, Macroeconomic Dynamics, forthcoming.

Zymek, R (2012), “Sovereign default, international lending, and trade”, IMF Economic Review 60(3): 365-394.

Endnotes

[1] This is mostly implied by constant elasticity of substitution preferences in gravity-type studies

[2] The most important advantage of this DSGE model is the ability to estimate its parameters using quarterly series, which is useful (and necessary) to identify the stories contributing to the Great Trade Collapse. The model considers individuals, manufacturers and retailers, where the latter two hold inventories of finished goods. There is a monetary authority who decides the policy rate, although the interest rate faced by individuals (due to intertemporal choices) and manufacturers and retailers (due to financial needs, including trade finance) is subject to a country-specific risk premium. To consider compositional effects, the model distinguishes between traded versus nontraded goods, home versus foreign goods, and durable versus nondurable goods.