The COVID-19 pandemic has not erupted across Africa with the ferocity it has elsewhere, at least not yet. Recorded COVID-19 deaths across the continent stood at around 25,000 by mid-August 2020, with approximately half of these recorded in South Africa. This is around 3% of global fatalities while Africa accounts for 17% of global population – although there are concerns about underreporting of cases and fatalities.

But the economic effects of the pandemic are already widespread and disproportionate to the public health impact. This reflects the rapid and aggressive implementation of lock-down measures across most of sub Saharan Africa, from as early as the second week in March (Hale et al. 2020). These have had a direct impact on economies, curtailing economic activity, forcing businesses to operate at inefficient scale: lockdowns are a significant supply shock (Brinca et al. 2020). Subsequently, they reduce domestic demand and further squeeze tax revenues just when governments are seeking to increase spending on health and social protection.

The bigger part of the economic hit, however, comes from the effects of the sharp contraction in global economic activity. The collapse in key commodity prices, most notably oil and minerals (although not gold); the effective closure of key export service sectors, including tourism; the sudden stops to new debt and FDI flows; and the drying-up of remittance flows constitute an external demand shock that is both unprecedented in scale (at least outside situations of outright conflict) and is highly correlated across countries. As many commentators have noted, without a significant and coordinated international response the depth and likely duration of this shock puts at risk the development gains achieved by many African countries over the last 20 years.

The small open economies of sub-Saharan Africa cannot ‘do whatever it takes’: their capacity for fiscal adjustment – to support private absorption and welfare while still delivering critical public services and sustaining public investment – is highly constrained. And the scope for monetary policy to offset the domestic demand shock is limited and ineffective in the face of the international demand shock. In advanced economies, governments and central banks have used their balance sheets to support unprecedented stimulus programmes, which by early June 2020 were estimated by the IMF to be approaching US$ 10 trillion (Battersby et al. 2020). In addition to meeting the direct costs of tackling the pandemic, fiscal deficits have increased very sharply to provide transfers to firms and household, labour furlough schemes, debt forbearance, tax holidays, and other forms of relief.

In contrast, for countries where domestic borrowing capacity is highly limited and access to external markets is either impossible or prohibitively expensive, the fiscal tide flows in the opposite direction. While governments and central banks have moved decisively to ring-fence direct public health expenditures, to offer tax relief and to loosen monetary policy where possible, these measures are modest at best and funded in part by cuts elsewhere in public expenditures, most notably in public investment. The scale of the contraction in external demand combined with limited fiscal space means that without substantial external support, feasible policy packages in many sub-Saharan countries look much more like austerity programmes than the Keynesian stimulus seen elsewhere in the world.

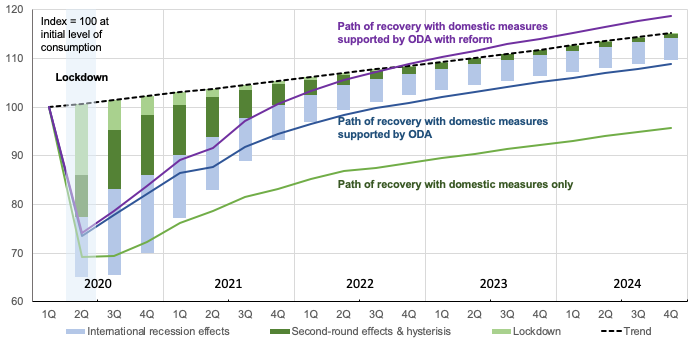

Our recent paper (Adam et al. 2020) uses a dynamic general equilibrium numerical simulation model to characterise the macroeconomics of the pandemic and its aftermath in sub-Saharan Africa. Calibrating the model to baseline data from Uganda and using emerging evidence on the severity of the global economic recession, we simulate the economic impact of the pandemic (the vertical bars) and how these paths are affected under alternative national and international policy responses (the lines).1

Figure 1 The impact of the pandemic and paths to recovery

Source: Adam et al. (2020). DOI: 10.1093/oxrep/graa023

With so much of the impact coming from the effect of the global slowdown on countries’ import capacity, the hit on consumption is substantially larger and more persistent than the effect of lockdown on domestic production and spending (Figure 1). Recovery depends on how the public finances are restored to sustainability. Even if politically feasible, raising taxes and cutting spending makes for a slow private sector recovery, especially if spending cuts fall on public investment and the maintenance of the public capital stock. This is particularly so in environments where tax systems are narrowly based and plagued by ‘leakages’ and exemptions. In such circumstances there are no easy public policy options.

If Official Development Assistance (ODA) supports domestic fiscal adjustment, the recovery may be accelerated. External finance widens fiscal space, so that domestic policy choices are less awful; it relieves the need to raise distorting taxes and cut productive spending. We calculate that a net increase in ODA of US$40-50bn would substantially ease the domestic adjustment challenge, even if this level of support cannot fully protect private incomes and expenditures, which matches recent estimates from the Director of the African Department at the IMF (Selassie 2020). Recovery would be further hastened if governments are able to take advantage of disruptive economic conditions to accelerate reforms designed to strengthen systems for tax collection and public spending.

External finance at this scale is significant but not unprecedented, either in the context of sub-Saharan Africa, being comparable to the HIPC (heavily indebted poor countries) debt relief programme in the mid-2000s, or in comparison to the approximately US$10 trillion that advanced economy governments have deployed to protect their own economies. To date, however, even though the IMF and World Bank have moved quickly to support many low-income countries, the response of the advanced economies remains muted.

There appears to be little appetite for a sustained coordinated effort amongst the leading economies to support adjustment in the LICs (McKibben and Vines 2020). This is short-sighted and contrary to appeals for action to the G20 (Berglof et al. 2020). The case for increased support can be based as much on national self-interest as on the moral and developmental arguments that hinge on growth and poverty reduction, especially at the bottom of the income distribution. There is a clear imperative to conquer the COVID-19 pandemic at a global scale so that it does not rip through the OECD again. Moreover, there is potential scope to ‘build back better’ with public investment that contributes to reduced carbon emissions, and supports economies to make the most of the potential demographic dividend offered by a youthful labour force across sub-Saharan Africa.

References

Adam, C, M Henstridge and S Lee (2020), “After the lockdown: macroeconomic adjustment to the COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36 (Supplement) (see also the working paper here).

Battersby, B, R Lam and E Ture (2020), “Tracking the $9 Trillion Global Fiscal Support to Fight COVID-19”, IMF blog.

Berglöf, E, G Brown, H Clark and N Okonjo-Iweala (2020), “What the G20 should do now”, VoxEU.org, 2 June.

Brinca, P, J B Duarte and M Faria-e-Castro (2020), “Measuring Sectoral Supply and Demand Shocks during COVID-19”, Covid Economics 20.

Hale, T, S Webster, A Petherick, T Phillips and B Kira (2020), Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government.

McKibben, W and D Vines (2020) “Global Macroeconomic Cooperation in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Roadmap for the G20 and the IMF”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36 (Supplement).

Selassie, A A (2020), “Africa’s Hour of Need”, Project Syndicate.

Endnote

1 The details of the modelling are set out in full in the working paper version of our paper here.