The European Commission plans to spend about €120 billion on research and innovation under mission-oriented programmes between 2021 and 2027. This column shows that planned spending is small both relative to total R&D spending of individual EU countries and relative to previous missions. In addition, there is a lack of clarity on how missions will be determined, designed and governed. Experiences in other countries suggest that the EC should find new ways of increasing funding to missions and increase clarity on the implementation of mission-oriented policies.

Mariana Mazzucato’s book, The entrepreneurial state, drastically changed how policymakers think about innovation policy and the appropriate role of government (Mazzucato 2013). This led to a renewed appreciation of mission-oriented innovation policies in the EU. About one third of the 224 EC documents on ‘mission-oriented’ policies after 2010 were in fact produced in 2018.1 Similarly, of about 30 academic articles on missions published after 2010, around one third were produced in 2018. There are also two special issues in Industrial and Corporate Change (Kattel and Mazzucato 2018) and Research Policy (Kuhlmann 2018) on mission-oriented and transformative innovation policies.

In this light, it is not surprising that Europe is moving towards mission-oriented policies to support innovation. At the beginning of 2018, the Commission announced that the new Framework Programme, Horizon Europe, will follow mission-oriented principles (Mazzucato 2018a). Accordingly, EU research and innovation efforts will be guided by ambitious and inspirational missions with clear targets addressing grand societal challenges.

What are missions?

Mission-oriented policies are supply- and demand-side market-shaping public policies that aim to affect the direction of technological change. For instance, the Apollo Project in the US (1961-1972) aimed at putting a ‘man on the moon’ but, as a by-product, contributed to new industries (such as micro-electronics and ICT) and created vast spillovers that continued for many years after the project ended.2

Taking the UN Sustainable Development Goals as a reference, the EU aims to replicate this experience by creating ‘new’ missions that will tackle grand societal challenges. Missions will be selected using five criteria (Mazzucato 2018a): (a) they are bold and inspirational with wide societal relevance; (b) they give a clear direction to research and innovation efforts by putting time-bound targets; (c) they are ambitious but realistic to achieve in a certain time period; (d) they should focus on solving the problem rather than on the actor, discipline or sector; and (e) they are flexible and open to multiple bottom-up solutions. Research and innovation projects financed by the Framework Programmes are supposed to tackle the specific problem defined under the mission.

Though not officially determined yet, Mazzucato (2018a, 2018b) presents possible examples for such new missions: 100 carbon-neutral cities by 2030 (climate change), a plastic-free ocean by 2025 (clean oceans), and decreasing the burden of dementia by halving the human burden by 2030 (citizen health and wellbeing).

Lack of clarity on how missions will be determined, designed and governed

Despite all the efforts of the Commission, it is still not clear how missions will be selected and what concrete difference they will bring to the ongoing thematic funding of the Framework Programmes. New missions are very different from the mostly defence-related old missions in terms of actor involvement, citizen engagement, centralisation of governance and their link to diffusion-oriented policies (Soete and Arundel 1993, Research Policy 2012). Designing missions to tackle grand societal challenges at the EU level is a giant policy experiment on its own – especially in an environment with 28 different national policies, procurement and investment systems as opposed to one single market.

How other EU programmes on regional development, cohesion and agriculture work for innovation missions is also not explicit. It is expected that missions will be created on overarching topics such as health, climate, digitalisation, transportation, and energy (Mazzucato 2018b). Looking at the above criteria and examples, it seems that funding of missions under the research and innovation programme will affect other EU programmes on agriculture, cohesion and environment. A portion of the planned spending on Regional Development & Cohesion (€273 billion), Agriculture & Maritime Policy (€372 billion) and Investing in People, Social Cohesion & Values (€140 billion) over the 2021-2027 period can, for instance, support missions directly by creating specific ‘innovation windows’ under each EU programme just as in the case of the new InvestEU programme. This will not only enhance interactions between programmes but also may provide additional funding for innovation missions (Foray et al. 2018) for the case of innovation and cohesion policies.

National R&D investments dwarf EU investments

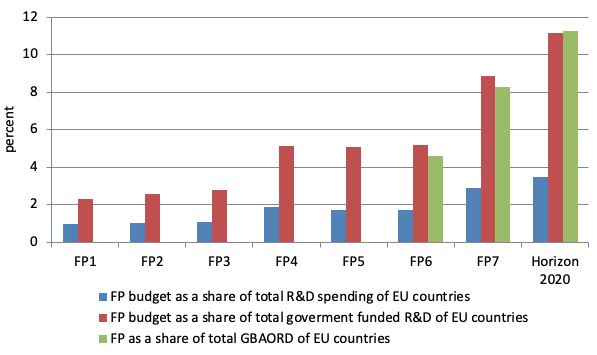

The Framework Programme is the main EU tool for supporting research and innovation activities. Total EU-level funding for the next round of the 2021-2027 Framework Programmes (Horizon Europe) will increase by 25% and reach €100 billion. While this is spectacular in absolute terms, EU funding is still small, compared to total national funding on R&D in individual EU countries. Figure 1 below shows that EU funding on Framework Programmes has risen from about 1% to 3.5% of total national spending of EU countries on R&D from Framework Programme 1 (1983-1987) to Horizon 2020 (2014-2020). In the same period, EU funding on Framework Programmes has risen from about 2% to 11.2% of national spending on R&D where the source of funding is the government.

Though it is difficult to differentiate R&D funding from innovation funding, the budgets of benchmark missions are comparably high. The US spent $25.4 billion on the Apollo Project (1961-1972), which was approximately 9% of national R&D spending in those years. Germany’s spending on the Energiewende is about 7-8%. The investment in the Second Delta Plan of the Netherlands of about €18 billion from 2017 to 2031 is about 7%. US spending on SunShot and total solar energy missions will reach $150 billion between 2016 and 2020 which is about 5%. China’s spending on New Energy Vehicles will be about 3% of its respective national R&D spending in designated periods.3

Thus, Horizon Europe’s 2021-2027 budget of about 4% relative to total national R&D spending of individual EU countries is low. Even if we assume that all of the Horizon Europe budget (€97.6 billion) will be directed to several, still undetermined missions and will include other initiatives that can partially be viewed as missions such as the European Space Agency (€16 billion) and Euratom (€2.4 billion), the €120 billion spending on research and innovation missions is still less than 5% of total national R&D spending of individual EU countries.

Figure 1 The budget of Framework Programmes as a share of total R&D spending of EU countries, 1983-2020

Source: Calculated using the Eurostat statistics. For data availability reasons and comparability with the EU definition before the enlargement in 2000, we used EU15 + Norway + Switzerland to calculate EU totals. In the current composition of the EU, the EU15 constitutes 95 percent of the total EU R&D spending (2016 numbers). Even then, about 15% of the cells that are used in the calculations are imputed.

As the mentioned facts and numbers show, missions around the world tend to spend more both in absolute and relative terms. It is still not clear how the EU will design the missions, how this will affect the current thematic funding of the Framework Programmes, and how the policy mix that will financially support the missions is determined. All in all, experiences in other countries suggest that the European Commission should both find new ways of increasing funding to missions and increase clarity on the implementation of mission-oriented policies.

The next Framework Programme, Horizon Europe (2021-2027), will be guided by mission-oriented policies and will be a learning period not only for beneficiaries but also for policymakers, civil servants and practitioners. To be successful, missions need to be clearly defined and well-funded. There is much to do in terms of reallocation of funds within the EU budget and between national governments and the EU, which may entail restructuring of EU institutions and programmes to work for missions.

References

Foray, D, D C Mowery and R R Nelson (eds) (2012), “Special Issue: The need for a new generation of policy instruments to respond to the Grand Challenges”, Research Policy 41(10): 1697-1792.

Foray, D, K Morgan and S Radosevic (2018), “The role of smart specialisation in the EU research and innovation policy landscape”, European Commission.

Kattel, R and M Mazzucato (2018), “Special issue: Mission-oriented innovation policy and dynamic capabilities in the public sector”, Industrial and Corporate Change 27(5).

Mazzucato, M (2013), The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs. private sector myths, London: Anthem Press.

Mazzucato, M (2018a), “Mission-oriented research & innovation in the European Union: A problem-solving approach to fuel innovation-led growth”, European Commission.

Mazzucato, M (2018b). “Analysis report to responses to the call for feedback on “Mission-oriented research & innovation in the European Union””, European Commission.

Kuhlmann, S (ed) (2018), “Special section on the past and future of innovation policy”, Research Policy 47(9): 1553-1584.

Soete, L and A Arundel (eds.) (1993), “An integrated approach to European innovation and technology diffusion policy: a Maastricht memorandum”, European Commission.

Endnotes

[1] For the whole list of EC documents, see https://tinyurl.com/y87wahvo.

[2] See, for instance, the leaflet “NASA Facts” published in July 2004 (https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/80660main_ApolloFS.pdf) presenting various examples of technologies that resulted from the Apollo Project.

[3] The calculations are based on the EC’s detailed documentation on 16 benchmark mission cases around the world and Eurostat statistics on spending on R&D. From the cases it is not possible to differentiate R&D and innovation spending. There is an indication of a budget that is supposedly spent to support the mission in each case.