After the financial crisis of 2008 several central banks cut their policy rates to zero, with urgent need for further stimulus in the years that followed. Many policies were tried, such as forward guidance, various credit easing measures, and fiscal policy, to name a few. These policies have garnered considerable attention and research, yet there is little consensus on their efficiency. Another policy, which has attracted somewhat less attention and research, is negative policy rates, as has been implemented by the central banks of Denmark, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, and the euro area. There is, however, even less consensus on the overall effect of this policy.

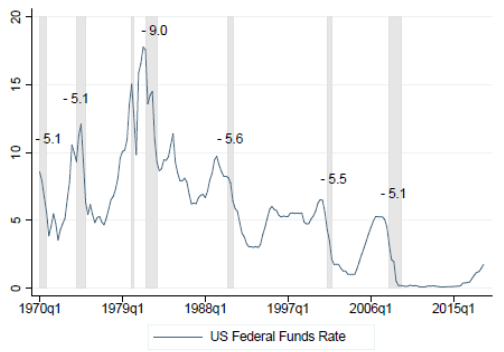

In a recent paper, Kiley and Roberts (2017) estimate that the zero lower bound (ZLB) will bind 30-40% of the time going forward. In Figure 1 we report interest rate cuts during previous recessions in the US and the euro area since 1970. On average, nominal interest rates are reduced by 5.9 and 5.5 percentage points, respectively, in response to a recession. With record low interest rates, policy rate cuts of this magnitude will be difficult to achieve in the future – without rates going negative. Accordingly, and given uncertainty about alternative measures, understanding the effectiveness of negative interest rate should be a top priority for applied monetary research.

Figure 1 Interest rates for the US and the euro area

Source: St. Louis FRED.

In a recent paper (Eggertsson et al. 2019) we consider the experience of several central banks with negative interest rates. We focus especially on Sweden as, among other things, we have daily bank-level data on listed mortgage rates for Swedish banks and can therefore more plausibly identify the transmission of policy rates to bank lending rates.

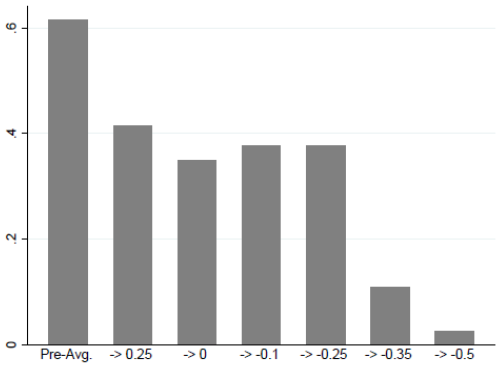

The evidence suggests that while the first two cuts by the Riksbank (to -0.10 and -0.25 respectively) appear to have been transmitted to lending rates, the second two cuts were not. Once the rates went down to -0.35 and -0.50 this may even have triggered an increase (albeit small) rather than a decrease in listed mortgage rates. This appears consistent with the cautionary note by the Riksbank when embarking on this untested strategy. The Riksbank said they expected that policy rate cuts to negative territory would work “at least when the cuts in total are not very large”, indicating concerns about the transmission mechanism for deep cuts. The evidence below suggests that negative interest rate cuts do indeed run into diminishing returns, although the question of where this starts is likely to be country specific and is still subject to considerable uncertainty, with more experience needed to tease out the exact turning point. Generally, one critical point seems to be reached once deposit rates – the main financing source of banks which, as we document below, appear to be bounded by zero – are no longer responsive to further policy rate cuts. In the Swedish case this looks to have been at around -0.25% for the policy rate. At this point, the traditional bank lending channel of monetary policy appears to break down.

When deposit rates became unresponsive in Sweden

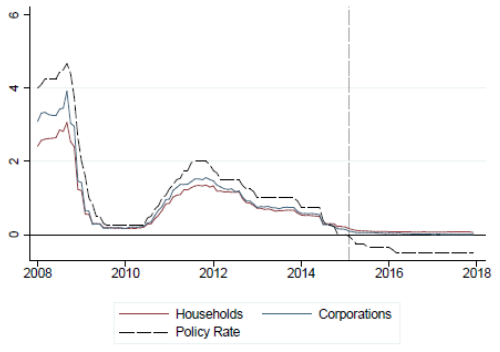

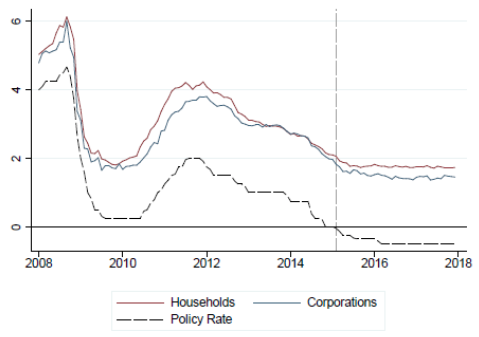

In Figure 2 we show that bank deposit rates – the rates commercial banks offer their customers – usually follow the policy rate closely. The traditional account of the bank channel of monetary policy is that policy rate cuts lead to lower deposit rates – an important source of bank financing, albeit relatively low in Sweden in an international context at only 50% – which then gets transmitted to the lending rates the banks offer their borrowers, thus stimulating spending and aggregate demand. Once the policy rate crossed the zero threshold, however, deposit rates in Sweden did not follow into negative territory. The same applies to deposit rates for the other countries that implemented negative policy rates.

Figure 2 Aggregate deposit rates in Sweden

Notes: The policy rate is defined as the repo rate. The red and blue dashed lines in the bottom panel capture counterfactual deposit rates calculated under the assumption that the markup to the repo rate was constant and equal to the average markdown in the period 2008m1-2015m1.

Source: The Riksbank, Statistics Sweden.

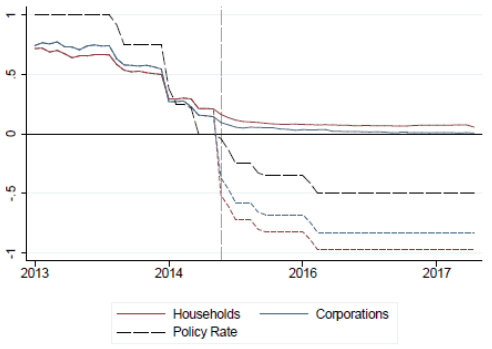

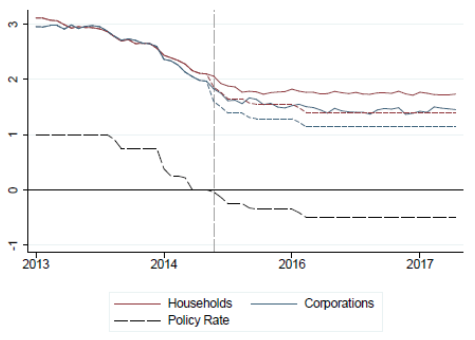

Perhaps somewhat subtly, there was still transmission to deposit rates for the first two interest rate cuts into negative territory – that is, when the Riksbank cut the policy rate to -0.1 and -0.25, respectively (see Figure 3). At the time of these cuts, the deposit rate had not quite hit zero and transmission was about 40% – not too far off the transmission of policy rate cuts for the previous two cuts when rates were positive. It was when the last two interest rate cuts (i.e. to -0.35 and -0.5) occurred that transmission to deposit rates collapsed. Below we document that in response to these last two cuts, lending rates, as measured by listed mortgage rates, stopped responding as usual.

Figure 3 Change in the aggregate deposit rate for households relative to the change in the repo rate, at times of changes to the repo rate

Source: The Riksbank, Statistics Sweden.

Apart from deposit collection, banks also finance themselves via issuance of bonds – in the case of Sweden, via covered bonds in particular – and with fees. While transmission to deposit rates ultimately collapsed, transmission to covered bond rates was stronger (although it did weaken as well). Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, however, banks did not increase their financing in terms of covered bond issuance during the negative rate period. Instead, they modestly increased their reliance on deposits. Similarly, while there was some increase in bank fees, this was not enough to substitute for the banks’ inability to charge negative rates on deposits. This suggests that deposit rates were an important contributor to banks’ marginal cost of financing, which is critical to explaining what happened to lending rates.

Pass-through to lending rates

Figure 4 shows the evolution of aggregate lending rates, showing that they typically follow the policy rate closely, albeit with variable markups. In the bottom panel we include a dashed ‘counterfactual’ path showing how one would have expected mortgage rates to behave if they had a constant and unchanged markup over the policy rate (relative to the pre-zero period). Clearly, mortgage rates stayed elevated compared to what this thought experiment would suggest. This can hardly be conclusive evidence, however, since it is well known that bank markups vary over time for various reasons.

Figure 4 Aggregate lending rates in Sweden

Notes: The policy rate is defined as the repo rate. The red and blue dashed lines in the bottom panel capture counterfactual lending rates calculated under the assumption that the markup to the repo rate was constant and equal to the average markup in the period 2008m1-2015m1.

Source: The Riksbank, Statistics Sweden.

In general, it is difficult to draw inference from aggregate lending data alone. Daily bank-level data on listed mortgage rates allow firmer conclusions, and such data are available for Sweden. Using listed daily data on mortgage rates, in Eggertsson et al. (2019) we use regression analysis to show that for the last two interest rate cuts by the Riksbank, mortgage rates stopped responding to the policy rate cuts – if anything they may even have slightly increased. The sharp change in the behaviour of listed rates to changes in the policy rate holds for three-month, one-year, three-year, and five-year contracts and is statistically significant. It suggests that these policy rate cuts did not have the same effect of stimulating lending via the traditional bank lending channel and had a fundamentally different effect than traditional interest rate cuts.

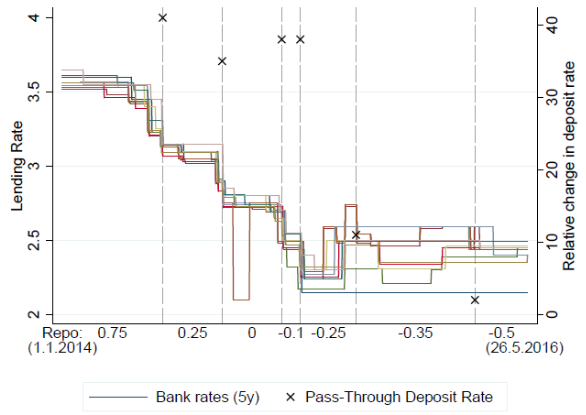

While three-month floating rate mortgages are the most common form of mortgage in Sweden, the breakdown in passthrough is most visually arresting for the case of five-year mortgages, common elsewhere in the world. Figure 5 shows how five-year mortgages responded to policy cuts for the 13 major Swedish banks in a daily dataset. The first two vertical lines show interest rate cuts in positive territory. Clearly, listed mortgage rates moved very closely with the policy rate cuts across the banks in the data sample. The third and fourth lines show the first two policy rate cuts in negative territory. There seems to have been some pass-through to lending rates (as deposit rates were still responsive), although also an increase in dispersion in the listed mortgage prices relative to regular cuts. The last two vertical lines capture the final two interest rate cuts in negative territory. Here, we see a fundamentally different response. In our paper we provide a formal model that accounts for this abnormal behaviour once the bound on deposit rates, derived in the model, is reached.

Figure 5 Bank level lending rates in Sweden

Notes: Interest rate on mortgages with five-year fixed interest period. The vertical lines mark days on which the repo rate was lowered. The label on the horizontal axis shows the value of the repo rate. Small crosses denote the change in the deposit rate relative to the change in the policy rate (%), measured on the right vertical axis.

Source: Compricer.se

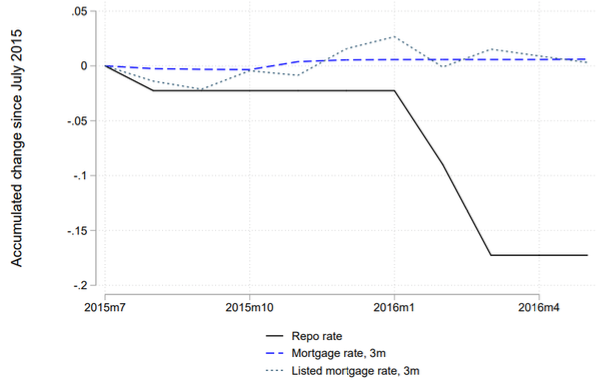

An important concern with the use of data for listed mortgage rates is that there is a difference between the listed rates and actual mortgage rates, as some customers are able to negotiate lower rates, thus pulling down the average actual rate relative to listed rates. We show, however, that once the bank-level data on listed mortgages are aggregated up they track official aggregate mortgage rates well. And while there is a modest level difference between the two series reflecting bargaining, this difference does not increase once rates turn negative. This is shown in Figure 6, where the listed and actual rates modestly increase following the interest rate cuts, in sharp contrast to normal interest rate cuts where the pass-through is more direct and immediate.

Figure 6 Accumulated changes in repo rate, listed three-month mortgage rates and aggregate three-month mortgage rates since July 2015

Source: Statistics Sweden and compricer.se

Slow transmission with deeply negative rates?

In a recent Vox column, Erikson and Vestin (2019) suggest, in contrast to our preceding arguments, that there was also full pass-through for the last two interest rate cuts in negative territory to household lending rates in Sweden. Their argument is that their measure of mortgage rates started to decline in the autumn of 2016 and well into 2018, more than two years after the Riksbank undertook the last policy rate cut to -0.5 (which happened on 17 February 2016). While we have documented that the policy rates typically filtered immediately into listed mortgage rates on previous occasions, their argument is that the pass-through for the last two cuts took longer to materialise. While this is certainly a possibility, there are several other forces that affect the markup of lending rates relative to the financing costs of banks than the policy rate. For example, one plausible candidate for lower mortgage rates in the latter half of 2016 and into 2017, which is independent of the effect of the policy rate cut in February 2016, is that the Financial Supervisory Authority of Sweden implemented amortisation requirements on 1 June 2016 with the goal of reducing household debt, loan-to-value ratios, and debt to income.1 This policy had the direct goal of reducing the riskiness of new mortgages and, if successful, should have reduced effective rates via lower risk premia.2 The regulation was further tightened on 1 March 2018. The Financial Supervisory Authority reported that the policy had been successful in lowering loan-to-value ratios (Finansinspektionen 2018). Similarly, from 2016 onwards the improving strength of the Swedish economy, driven by a host of factors, might also have worked towards lowering the overall riskiness of mortgages and towards reducing borrowing rates. Both examples – and surely others could be found – point to the challenges associated with causal identification in the case of monetary policy and the value of complementary analysis in structural models where counterfactuals can be clearly identified. In Eggertsson et al. (2019) we provide one example of such a model and its prediction is consistent with our suggested interpretation.

Conclusion

The question of whether negative policy rates are a viable policy tool for stimulating demand is a fundamental one in preparing for the next recession. The Riksbank should be commended for paving the way in experimenting with this tool and for its openness in debating the effect these policies have had (see Erikson and Vestin 2019 for a case in point). We argue that while the first two cuts in negative territory in Sweden might have been transmitted to lower lending rates for mortgages, this does not seem to be the case for the last two cuts in negative territory, as the Riksbank seems to have anticipated, suggesting diminishing returns on interest rate cuts at negative interest rates. Nevertheless, it is worth highlighting that it is quite possible that those policy rate cuts had a desirable effect via other channels. These channels may – somewhat speculatively – include the effect on asset prices or the exchange rate. Also, there is evidence of an effect on lower financing costs via government bond rates, leaving more fiscal space for government stimulus, as well as an effect on some corporate rates. Future research will need to determine how important these channels are, and when and if they also encounter diminishing returns if rates are moved deeper into negative territory.

References

Eggertsson, G, R Juelsrud, L H Summers and E G Wold (2019), “Negative Nominal Interest Rates and the Bank Lending Channel”, NBER Working Paper 25416.

Finansinspektionen (2018), The Swedish Mortgage Market.

Kiley, M T and J M Roberts (2017), "Monetary policy in a low interest rate world", Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2017(1): 317-396.

Erikson, H and D Vestin (2019), “Pass-through at mildly negative policy rates: The Swedish Case”, VoxEU.org, 22 January.

Endnotes

[1] Erikson and Vestin (2019) acknowledge that amortisation requirement may have played a role in endnote 13 of their column, but mainly emphasise the possibility that the banks had originally tried to exert their market power to keep rates higher but that this strategy was not sustainable on account of new entrants to the mortgage market. Future research will need to discriminate between these two hypothesis and other comparable ones.

[2] The new rule stipulated that all mortgage holders borrowing more than 50% of their property must pay down at least 1% of their mortgage per year, while those borrowing more than 70% must pay down at least 2% per year. Then, on 1 March 2018, an additional rule was imposed so that households borrowing more than 4.5 times their annual income must pay down an additional 1% per year (Finansinspektionen 2018). Erikson and Vestin (2019) also acknowledge that higher amortisation may have played a role (see endnote 13) but focus on the hypotheses that it was lack of competition that initially held rates higher, and that they were gradually competed down by new entrants in the mortgage markets. Future research might be able to discriminate between these two hypotheses and others.