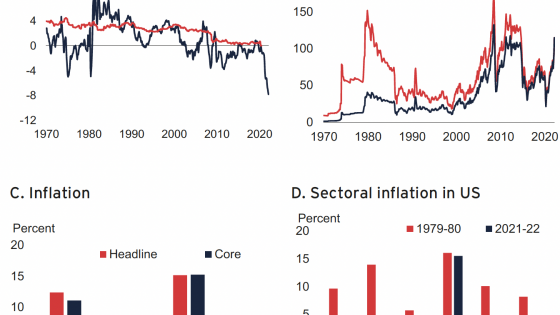

Global inflation has risen over the past year from less than 2% to over 6%, the highest level since 2008 (Figure 1a). Inflation is now running well above central bank inflation targets in almost all advanced economies and most inflation-targeting emerging market and developing economies (Figure 1b). The recent commodity price surge triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will raise inflation further in 2022 (Seiler 2022).

Over the medium term, current inflation expectations point to a return of inflation to low and within-target inflation. There is a material risk, however, that repeated inflationary shocks and a prolonged period of high inflation eventually de-anchors inflation expectations (D'Acunto and Weber 2022). This would mark a turning point after two decades of low and stable inflation.

Figure 1 Inflation

Sources: Haver Analytics; World Bank.

Note: EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies. Year-on-year inflation. A. CPI refers to consumer price index. Lines show group median inflation for 81 countries, of which 31 are advanced economies and 50 are EMDEs. Last observation is February 2022. B. Bars show the share of inflation-targeting countries (in percent) with average inflation during the course of the year (or month) above the target range.

The period of high and variable inflation rates of the 1970s offers some salutary lessons for the current period. In our new CEPR Policy Insight, we examine the main similarities and differences between the current juncture and the 1970s to shed light on the question of whether we are witnessing the end of the era of low inflation (Ha et al. 2022). Echoes of the Great Inflation of the 1970s and fading structural forces of disinflation may be reasons to believe so; expectations that recent cyclical shocks will subside, and decades of building central bank credibility and anchoring expectations, may be reasons to disagree.

Déjà vu all over again: Similarities to the 1970s

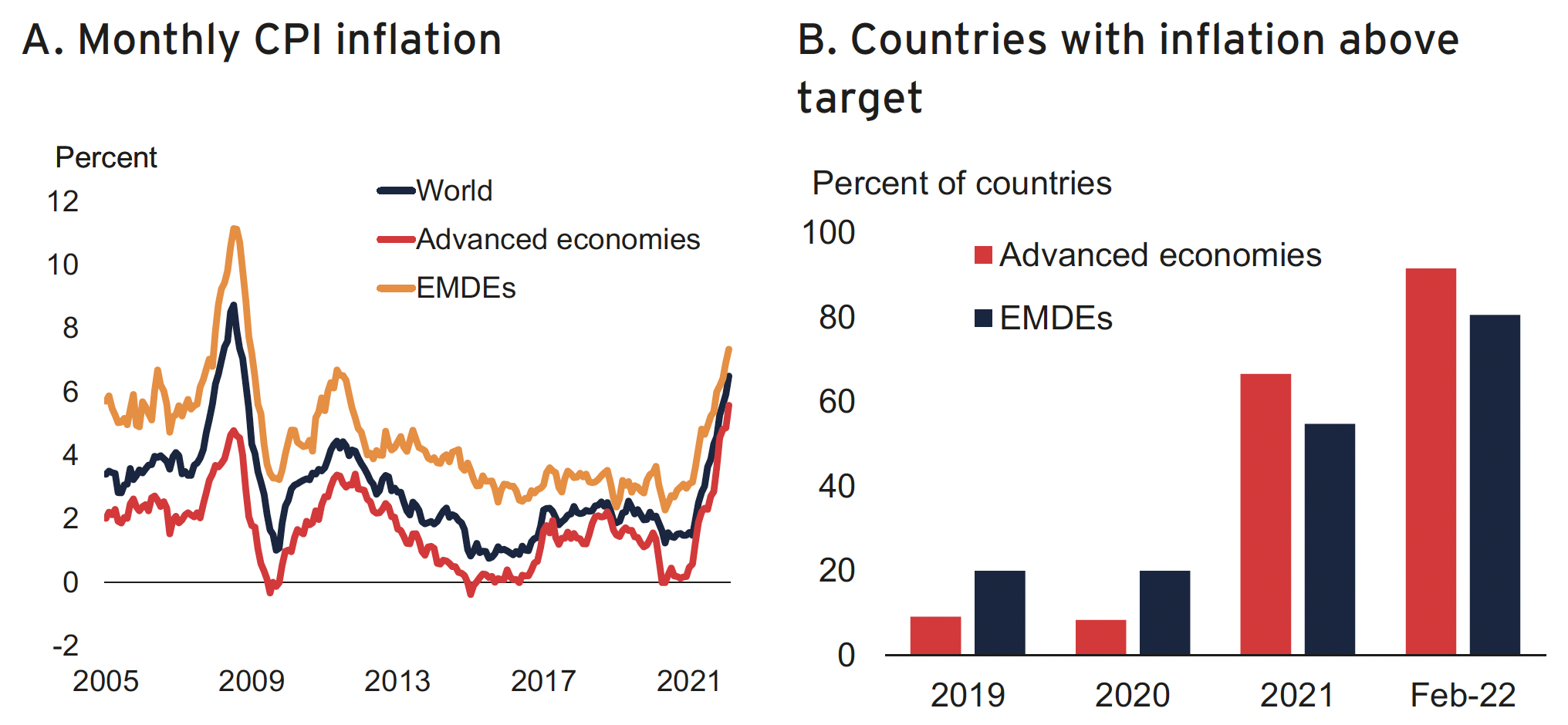

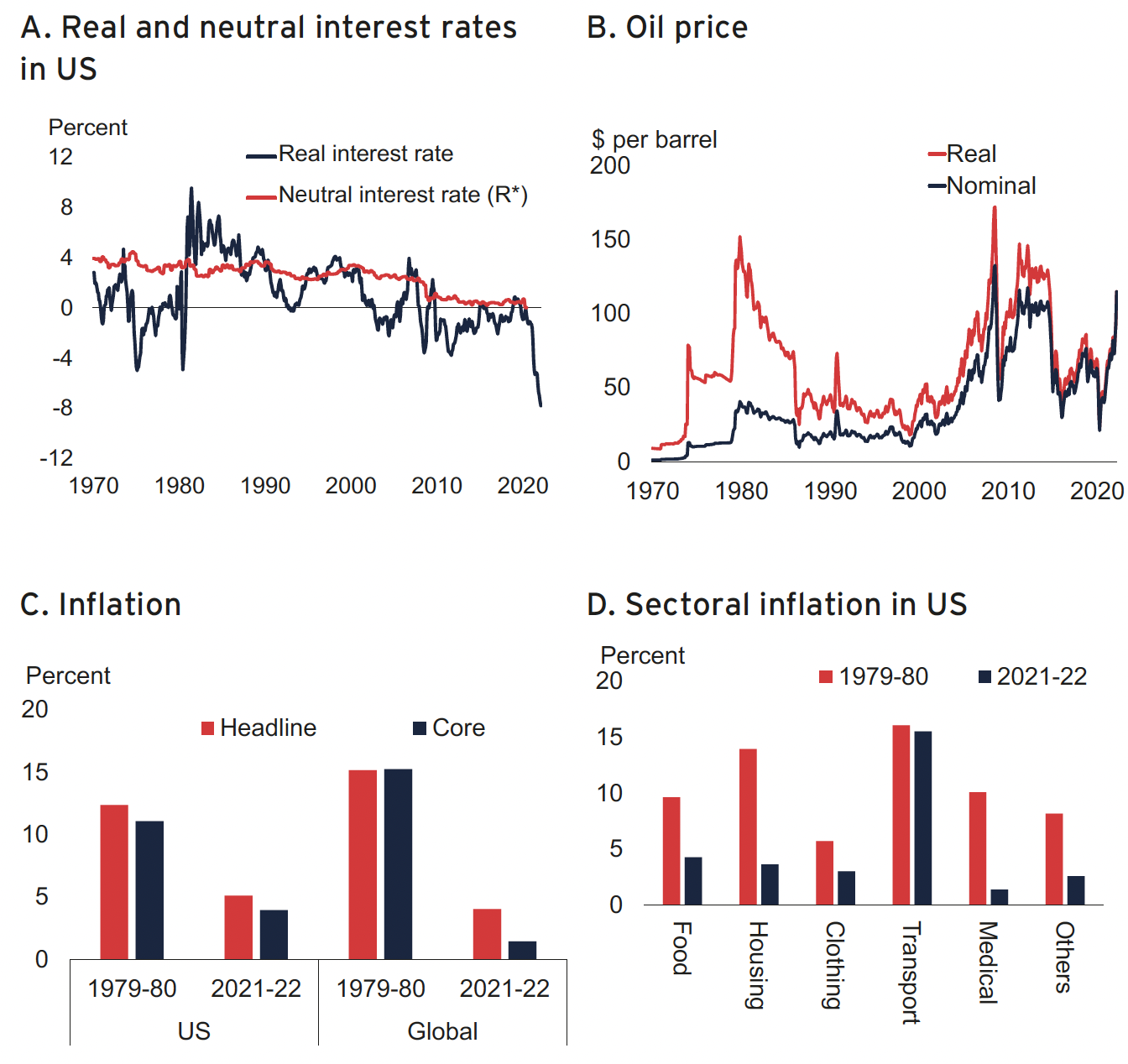

In light of the experience of the 1970s, the case for a protracted period of high inflation is straightforward. First, supply disruptions driven by the pandemic and the recent supply shock dealt to energy prices by the war in Ukraine resemble the oil shocks in 1973 and 1979–80. Second, then and now, monetary policy was highly accommodative in the run-up to these shocks (Figure 2a). After several months of above-target inflation in major advanced economies, a steeper-than-anticipated policy tightening might now be required to return inflation to target – and this might trigger a hard landing similar to that of the early 1980s (Blanchard 2022, Summers 2022, Gagnon 2022).

Differences from the 1970s

There are important differences between the current situation and the 1970s. First, at least thus far, the magnitude of commodity price jumps has been smaller than in the 1970s. In the wake of major oil shocks, oil prices quadrupled in 1973-74 and doubled in 1979-80. The combination of high inflation with weak economic growth, fuelled by repeated supply shocks, gave rise to the phenomenon of ‘stagflation’. Today, oil prices are, in real terms, still only around two-thirds of those in 1980 or 2008 (Figure 2b).

Second, there has been a paradigm shift in monetary policy frameworks since the 1970s. In the 1970s, instead of today’s typically primary focus on inflation, central bank mandates incorporated multiple competing objectives, including for output and employment, as well as for price stability. Most central banks in advanced economies, freed in 1971 from the constraints of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, aimed to support economic activity with monetary expansion, without realising that potential output growth had started to slow (de Long 1997). Policymakers were inclined to attribute rising inflation to special factors, and underestimated the pervasive and lasting impact of excess aggregate demand pressures (Blinder 1982).

This ‘passive’ monetary policy stance resulted in a multi-decade period of rising and mostly elevated inflation. Global median inflation started the 1960s at a low 1.5% but then trended up rapidly, in the range of 1.5–4.7% through the 1960s. In 1970, it reached 5.5% and then continued to trend up in a range from 5.5–14.4% through the 1970s before culminating at 14% in 1980. In comparison, today’s global inflation is only recently above pre-pandemic levels, since mid-2021 (at 5% on average in 2021–22 and 7% in March 2022). That said, model forecasts and consensus expectations suggest that global inflation could rise to almost 10% later this year before it starts declining.

In contrast, central banks in advanced economies now have clear mandates for price stability, expressed as an explicit inflation target. They have adopted transparent operating procedures, announcing and justifying their settings for the policy rate. Over the past three decades, they have established a credible track record of achieving their inflation targets (Bordo et al. 2007, Eichengreen 2022).

Figure 2 Inflation and interest rates in the 1970s and 2020s

Sources: Holston et al. (2017); Federal Reserve Economic Data; Havers Analytics; World Bank.

Note: CPI: consumer price index. A. Real interest rates are based on effective federal funds rates – US CPI inflation. Neutral interest rates (R*) are the estimates of Holston, Laubach, and Williams (2017). B. Nominal and real crude oil prices (averages of Dubai, Brent, and WTI prices). Real oil prices are deflated by US CPI index (February 2022 = 100). C. Annual averages of headline and core CPI inflation in the United States and global (average across 40 countries). 2022 is based on the averages of January and February 2022. D. Sectoral CPI inflation (monthly averages of year-on-year inflation) in the United States. 2022 is based on the averages of January and February 2022. “Others” includes communication, recreation, education, restaurants, and miscellaneous sectors.

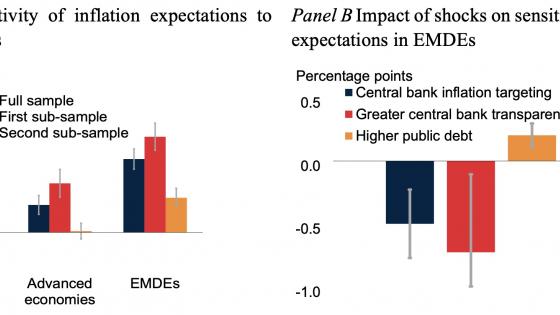

As a result of such improvements in policy frameworks and better anchored inflation expectations, inflation – in particular, core inflation – has become much less sensitive to inflation shocks (Ha et al. 2022, Figure 2c). In addition, for now, inflation increases have been concentrated narrowly in a few energy-intensive and pandemic-affected sectors, although there are signs that inflation pressures may have been broadening recently. This stands in contrast to 1979–80, when the inflation acceleration was broad-based, with similarly high inflation rates cutting across virtually all sectors (Figure 2d) Hence, inflation in some sectors is expected to decline once supply disruptions ease and commodity prices stabilise (Borio et al. 2022, Ilzetzki 2022).

Lessons from the 1970s for the 2020s

Eventually, aggressive monetary policy tightening in the late 1970s and early 1980s sharply reduced inflation in advanced economies and established central bank credibility, although often at the cost of deep recessions (Goodfriend 2007). In the US, for example, short-term interest rates almost quadrupled between the end of 1976 and mid-1981. In the wake of these interest rate increases, US output contracted by more than 2% between early 1981 and mid-1982. In some advanced European economies, central banks set a higher priority on inflation control, and responded earlier to rising inflation. As a result, in several of these economies, the inflation cycle was less pronounced than in the US, but it was also accompanied by recessions in the early 1980s.

In the near term, inflation is likely to remain elevated as demand and supply shocks pass through wage- and price-setting processes. Beyond the near term, inflation is expected to decline, but the experience of the 1970s suggests some material risks to this inflation outlook.

Three factors suggest that, globally, inflation is likely to return to target rates in the medium term. First, as central banks tighten monetary policy and pandemic-related fiscal stimulus is unwound, growth will slow; as the supply disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine are priced in, commodity prices will stabilise; and as global production lines and logistics adjust, supply bottlenecks will ease (Reifenschneider and Wilcox 2022, Ilzetzki 2022). Second, after decades of building credibility, inflation expectations are likely to remain well anchored over the medium term (Armantier et al. 2022, Bordo and Orphanides 2013). Finally, as long as the structural forces that depressed inflation before the pandemic persist, trend inflation will continue to be low (Ha et al. 2019).

However, a considerable risk remains that some of these three factors will not materialise as expected and inflation will remain high. First, stagflationary shocks could become more frequent or more pronounced and cause repeated inflation overshoots that may eventually de-anchor inflation expectations. Second, central banks may remain hesitant in their response and could fail to reach their targets so often that economic agents eventually lose faith in their commitment or ability to maintain price stability and inflation expectations become de-anchored. Third, the structural forces that have depressed inflation over the past decade may fade (Gersbach 2021).

This uncertain outlook poses serious policy challenges for central banks. However, it does not require them to deviate from the fundamentals that have helped them build credibility over the past three decades. They need to calibrate their policies with macroeconomic stability in mind, communicating their plans clearly, and preserving their credibility. The prospect of a protracted period of high inflation and a sharp increase in global interest rates has significant implications for emerging market and developing economies, as discussed in our Policy Insight.

References

Armantier, O, L Goldman, G Kosar, G Topa, W van der Klaauw and J C Williams, (2022), “What Are Consumers’ Inflation Expectations Telling Us Today?”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, 14 February.

Blanchard, O (2022), “Why I Worry About Inflation, Interest Rates, and Unemployment,” Realtime Economic Issues Watch, 14 March.

Blinder, A S (1982), “Chapter 12: The Anatomy of Double-Digit Inflation in the 1970s”, in R E Hall (ed.), Inflation: Causes and Effects, University of Chicago Press, p.261-282.

Bordo, M D, C Erceg, A Levin, and R Michaels (2007), “Three Great American Disinflations”, NBER Working Paper 12982.

Bordo, M D and A Orphanides (eds) (2013), The Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central Banking, University of Chicago Press.

Borio, C, P Disyatat, D Xia, and E Zakrajšek (2022), “Looking under the Hood: The Two Faces of Inflation”, VoxEU.org, 25 January.

D’Acunto and M Weber (2022), “Rising Inflation Is Worrisome. But Not for the Reasons You Think”, VoxEU.org, 4 January.

DeLong, J B (1997), “America’s Peacetime Inflation: The 1970s”, in C D Romer and D H Romer (eds), Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy, University of Chicago Press, pp. 247-80.

Eichengreen, B (2022), “America’s Not-so-Great Inflation,” Project Syndicate, 10 February.

Gagnon, J E (2022), “Why US Inflation Surged in 2021 and What the Fed Should Do to Control It”, PIIE series on inflation, 11 March 11, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Gersbach, H (2021), “Another Disinflationary Force Vanishes: The Tightening of Bank Equity Capital Regulation”, VoxEU.org, 18 February.

Goodfriend, M (2007), “How the World Achieved Consensus on Monetary Policy”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(4): 47-68.

Ha, J, M A Kose and F Ohnsorge (eds) (2019), Inflation in Emerging and Developing Economies: Evolution, Drivers, and Policies, World Bank.

Ha, J, M A Kose and F Ohnsorge (2021), “One-Stop Source: A Global Database of Inflation”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16327.

Ha, J, M A Kose and F Ohnsorge (2022), “From Low to High Inflation: Implications for Emerging Market and Developing Economies”, CEPR Policy Insight 115.

Ha, J, M A Kose, H Matsuoka, U Panizza and D Vorisek (2022), “Anchoring Inflation Expectations in Emerging and Developing Economies”, VoxEU.org, 14 July.

Holston, K, T Laubach, and J C Williams (2017), “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International Trends and Determinants”, Journal of International Economics 108: S59-S75.

Ilzetzki, E (2022), “Surging inflation in the UK”, VoxEU.org, 10 February.

Reifenschneider, D and D Wilcox (2022), “The Case for a Cautiously Optimistic Outlook for U.S. Inflation,” PIIE Policy Brief 22-3, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Seiler, P (2022), “The Ukraine War Has Raised Long-term Inflation Expectations”, VoxEU.org, 12 March.

Summers, L (2022), “The Fed is Charting a Course to Stagflation and Recession”, The Washington Post, 15 March.