Creating and sustaining a healthy and supportive workplace environment is of crucial importance for both the wellbeing of employees and the productivity and reputation of firms. At the very heart of such a healthy work environment lies the quality of social interactions among colleagues and between leaders and subordinates (Dutton and Ragins 2017, Kahn et al. 2018, Alan et al. 2023a). The interactions between leaders and their subordinates are particularly important as the leaders typically set the tone for the relational culture in the workplace. Accordingly, there has been a growing interest in understanding what makes a good leader in terms of skills and qualities (Lazear et al. 2015, Deming 2017, Heinz et al. 2020, Englmaier et al. 2021).

In a recent project (Alan et al. 2023b), we investigate the role of gender – and in particular, of female leadership – in transforming the relational atmosphere in the workplace (Matsa and Miller 2013, Chakraborty and Serra 2022). More specifically, we first explore how male and female team leaders differ in their cognitive and socio-cognitive skills as well as their economic and social preferences. We then explore the impact of female leadership on the structure of social relationships within firms, job separations, and promotions, and the perceived workplace climate by employees.

We answer these questions empirically using data from over 2,000 white-collar professionals in 24 large corporations in Turkey. These data – collected via lab-in-the-field experiments and complemented with administrative data on promotions and separations – include information on the characteristics, social networks, and perceived climate of these white-collar professionals, elicited using cognitive tests, incentivised behavioural tasks, and surveys.

Based on our data from actual leaders and their subordinates, we focus on three sets of outcomes. Our first set of outcomes characterise the relational culture in the workplace. We specifically focus on whether female leaders differ from male leaders in providing support to their employees in both professional and personal matters, and whether this support varies by the gender of the subordinate. Additionally, we also measure gender segregation, in particular, male and female homophily in social networks at the department level. Second, we explore the layoffs, quits, and promotion. Finally, our third set of outcomes provides a detailed picture of perceived workplace climate in terms of perception of meritocratic values in the firm, collegiality, job satisfaction, behavioural norms, and leader professionalism.

In ensuring that the assignment of leaders to subordinates is not influenced by factors that can also affect the outcomes we focus on, we only included firms in our study that have established fair and transparent recruitment and team formation processes. This allowed us to credibly claim that leader gender is, in effect, randomly assigned, controlling for department characteristics and the nature of employees' work.

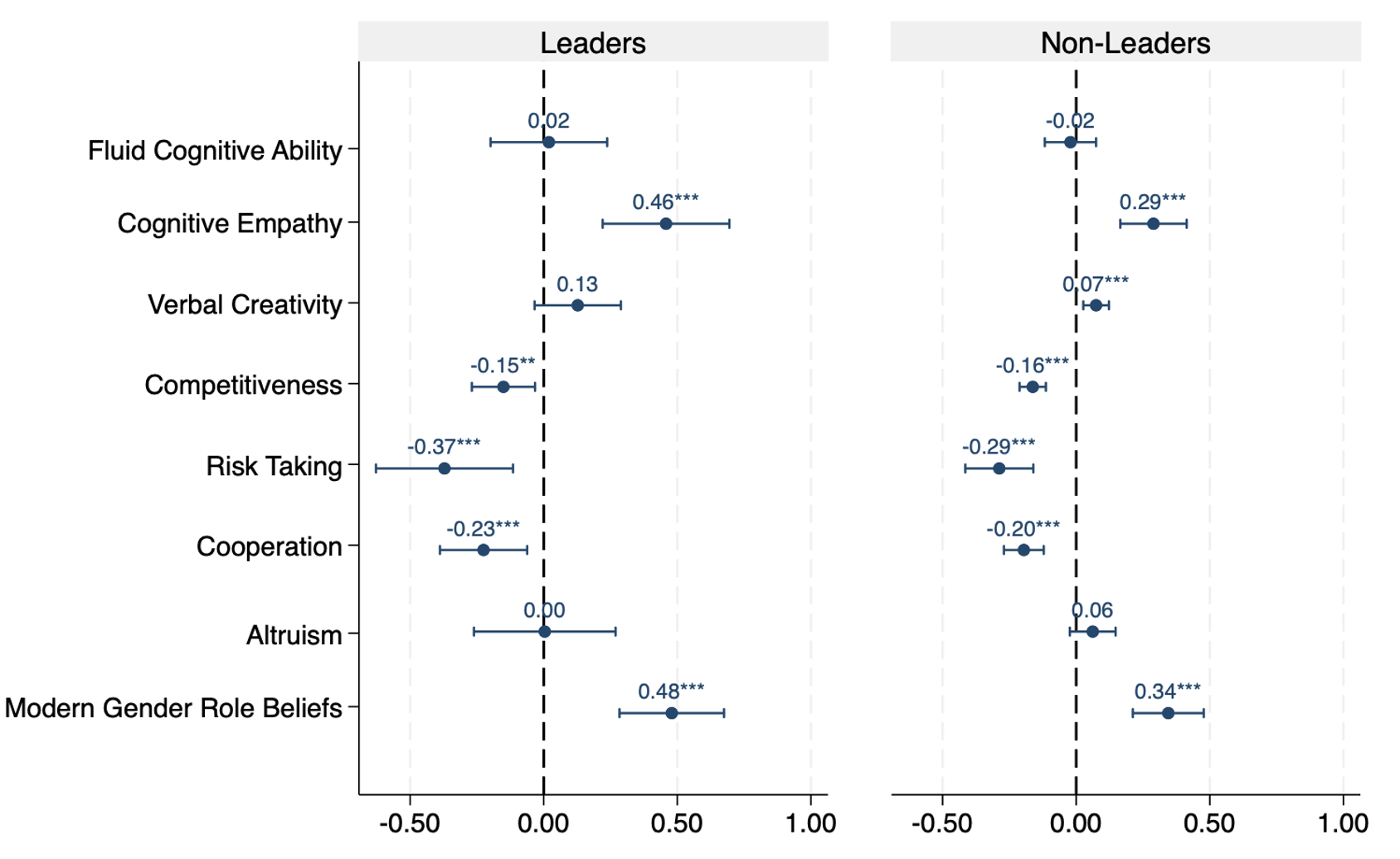

To begin with, our analyses reveal a novel insight about leaders. As reported in Figure 1, we find that progression into leadership positions does not require females to possess attributes that are typically associated with males, such as high competitiveness and risk tolerance. Interestingly, female leaders are significantly less competitive and more risk averse than male leaders. Yet, female leaders have higher cognitive empathy and hold more modern gender roles than male leaders. The two groups, however, do not differ from each other in terms of altruism, verbal creativity, and fluid IQ; the latter being the strongest predictor of holding a leadership position.

Figure 1 Gender differences in cognitive skills and economic preferences of leaders and non-leaders

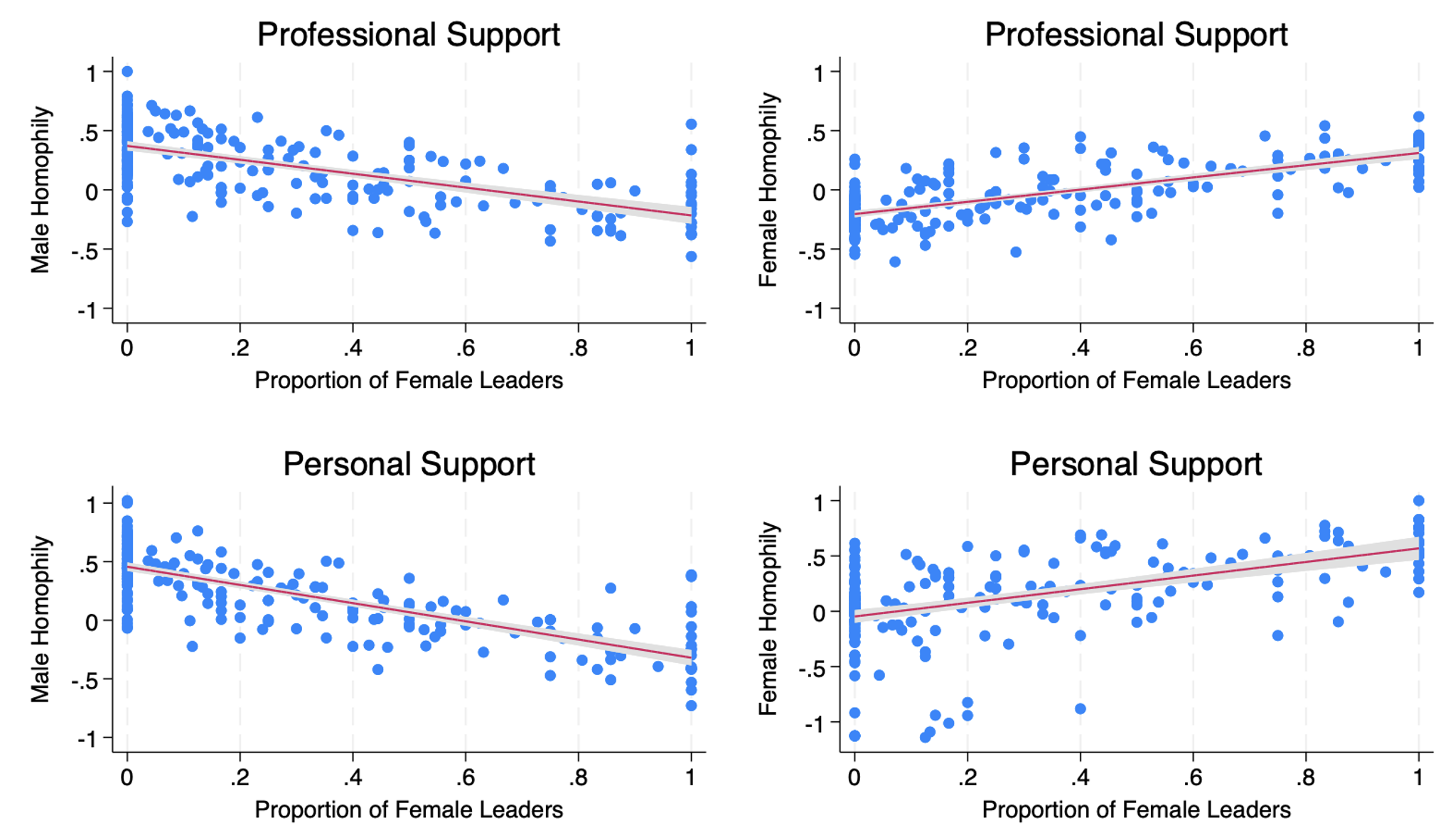

When it comes to relational structure in the workplace, we show that female employees are 20% and 46% more likely to receive professional and personal support, respectively, from female leaders than male leaders. Such a gender gap does not exist for male employees. Female leadership also leads both male and female employees to establish more ties with their female colleagues. Consistent with Cullen and Perez-Truglia (2023), we also show that males tend to interact more with male employees, referred to as ‘male homophily’. As Figure 2 shows, female leadership breaks this pattern and creates a less gender-segregated workplace.

Figure 2 Proportion of female leaders and homophily

The positive repercussions of female leadership is evident in the quit rates. Our findings indicate that female employees working under female leaders are 7 percentage points less likely to quit their jobs, implying a staggering 56% reduction in quit rates relative to females working under male leadership. We however do not find any effect of female leadership on promotions and layoffs.

What is at odds with the aforementioned positive impact, though, is that employees working under female leaders report significantly lower workplace satisfaction and worse meritocratic values for their firms, and that this is mostly driven by female employees working under female leaders. We posit that this could be due to higher expectations placed on female leaders by female subordinates. More specifically, when employees – both male and female – receive professional support from their leaders, the gender of the leader does not make a difference in perceived workplace climate perceptions. However, when female employees do not receive support from their female leaders, they paint a much darker perceived workplace climate. This nuanced finding is consistent with what Abel (2022) documents: negative feedback by especially female leaders decreases job satisfaction. Along similar lines, Grossman et al. (2019) and Chakraborty and Serra (2022) also show that female leaders receive more backlash and are evaluated more harshly than male leaders.

The implications of our findings are manifold. Our evidence suggests that female leaders significantly influence the structure of workplace networks, facilitating more inter-gender support links. This has important implications for policies aimed at reducing gender gaps in earnings and promotions, which are often exacerbated by gender homophily in professional networks and discussed in another Vox column (Dahl et al. 2021; see also Mengel 2020, Zeltzer 2020, and Cullen and Perez-Truglia 2023). Our research also contributes to the debate on leadership selection by highlighting that actual female leaders in competitive corporate environments do not necessarily exhibit the same attributes as their male leaders. Rather, they manifest a different leadership style that emphasises emotional intelligence over competitiveness or risk-taking. Moreover, we contribute to the debate on how female leadership impacts gender-related personnel decisions. Our study finds that female leadership can reduce job separations among female employees without impacting promotion probabilities, pointing towards the importance of female representation in leadership positions for creating a more inclusive workplace environment.

In sum, our results show that a fairer representation of female leadership may have benefits beyond efficiency and social justice concerns by creating a more inclusive and less segregated workplace, one in which employees and leaders form stronger inter-gender ties and female employees exhibit less voluntary quits. Given that cultural transformations may be painfully slow, promoting female leadership and improving support by leaders might be a faster and an easier approach to establishing a healthy workplace environment.

References

Abel, M (2022), “Do workers discriminate against female bosses?”, Journal of Human Resources.

Alan, S, G Corekcioglu and M Sutter (2023), “Improving workplace climate in large corporations: A clustered randomized intervention”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 138(1): 151-203.

Alan, S, G Corekcioglu, M Kaba and M Sutter (2023), “Female Leadership and Workplace Climate”, MPI Collective Goods Discussion Paper 2023/9.

Chakraborty, P and D Serra (2022), “Gender and leadership in organizations: The threat of backlash”, Working Paper.

Cullen, Z and R Perez-Truglia (2023), “The old boys’ club: Schmoozing and the gender gap”, American Economic Review 113(7): 1703-1740.

Dahl, G, A Kotsadam and D-O Rooth (2021), “Workplace integration and gender attitudes”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Deming, D J (2017), “The growing importance of social skills in the labor market”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(4): 1593-1640.

Dutton, J E and B R Ragins (2017), “Moving forward: Positive relationships at work as a research frontier”, in Exploring Positive Relationships at Work, Psychology Press.

Englmaier, F, S Grimm, D Grothe, D Schindler and S Schudy (2021), “The value of leadership: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment”, CESifo Working Paper 9273.

Grossman, P J, C Eckel, M Komai and W Zhan (2019), “It pays to be a man: Rewards for leaders in a coordination game”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 161: 197-215.

Heinz, M, S Jeworrek, V Mertins, H Schumacher and M Sutter (2020), “Measuring the indirect effects of adverse employer behaviour on worker productivity: A field experiment”, The Economic Journal 130(632): 2546-2568.

Kahn, W A, M A Barton, C M Fisher, E D Heaphy, E M Reid and E D Rouse (2018), “The geography of strain: Organizational resilience as a function of intergroup relations”, Academy of Management Review 43(3): 509-529.

Lazear, E P, K L Shaw and C T Stanton (2015), “The value of bosses”, Journal of Labor Economics 33(4): 823-861.

Matsa, D A and A R Miller (2013), “A female style in corporate leadership? Evidence from quotas”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(3): 136-169.

Mengel, F (2020), “Gender differences in networking”, The Economic Journal 130(630): 1842-1873.

Zeltzer, D (2020), “Gender homophily in referral networks: Consequences for the Medicare physician earnings gap”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(2): 169-197.