Productivity growth is considered to be a key driver of economic wellbeing. While policymakers are focusing on strategies to reverse the long-standing slowdown in productivity growth, growing concerns about whether an acceleration of productivity growth may harm employment have emerged.

The concerns about the possible negative impacts of technological change – a key engine of productivity growth – on employment are illustrated by recent discussions on the effects of automation. Some studies show adverse effects of robotisation on employment and wages (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017, Graetz and Michaels 2015), which are related to the disappearance of routine tasks (Autor et al. 2003). Rapid advances in artificial intelligence and the possibility of automating an increasing set of tasks have further fuelled public anxiety about looming technological unemployment (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020).

However, technological change may also trigger favourable employment responses. New technologies may create demand for new tasks in the labour market, such as the design, supervision, maintenance, and repair of machines (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2016). Moreover, firms that adopt productivity-enhancing technologies may become more competitive and increase sales, therefore increasing their use of inputs, including labour (Acemoglu et al. 2020, Aghion et al. 2020, Koch et al. 2019). Overall, the extent to which there may be a trade-off between productivity and employment growth is an open empirical question, which we address in this column.

Novel insights on the productivity-employment nexus across countries

Previous analyses of the productivity-employment nexus have generally focused on single countries, most often the US (e.g. Decker et al. 2020, Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017), and/or single aggregation levels (e.g. Aghion et al. 2020 at the firm level, or Autor and Salomons 2018 at the sectoral level). A comprehensive study across countries and levels of aggregation is, however, key to obtaining a complete picture of such a relationship.

Based on the OECD MultiProd database, a unique cross-country infrastructure collecting micro-aggregated representative data based on firm-level information, in a recent paper (Calligaris et al. 2023) we carry out a comprehensive analysis, based on 13 countries over the period 2000-2018, that explores the productivity-employment nexus at different levels of aggregation (firm level and more aggregate ones), for both manufacturing and non-financial market services.

The MultiProd database, among other things, includes measures of productivity, employment, and wages. Beyond aggregates at the level of the country, year and detailed industry, it encompasses breakdowns by groups of similarly productive firms, and by groups that feature similar productivity transition dynamics (for details, see Berlingieri et al. 2017), allowing us to zoom in on the productivity-employment nexus at a more granular level.

Within-firm productivity growth is positively linked to employment growth

Focusing on firm-level dynamics, we find that multifactor productivity and employment growth are overall positively linked. In this regard, two groups of firms stand out. From a static perspective, firms at the top of the productivity distribution experience higher employment growth. However, after accounting for initial differences in productivity, firms that improve their productivity more also experience stronger employment growth than other firms.

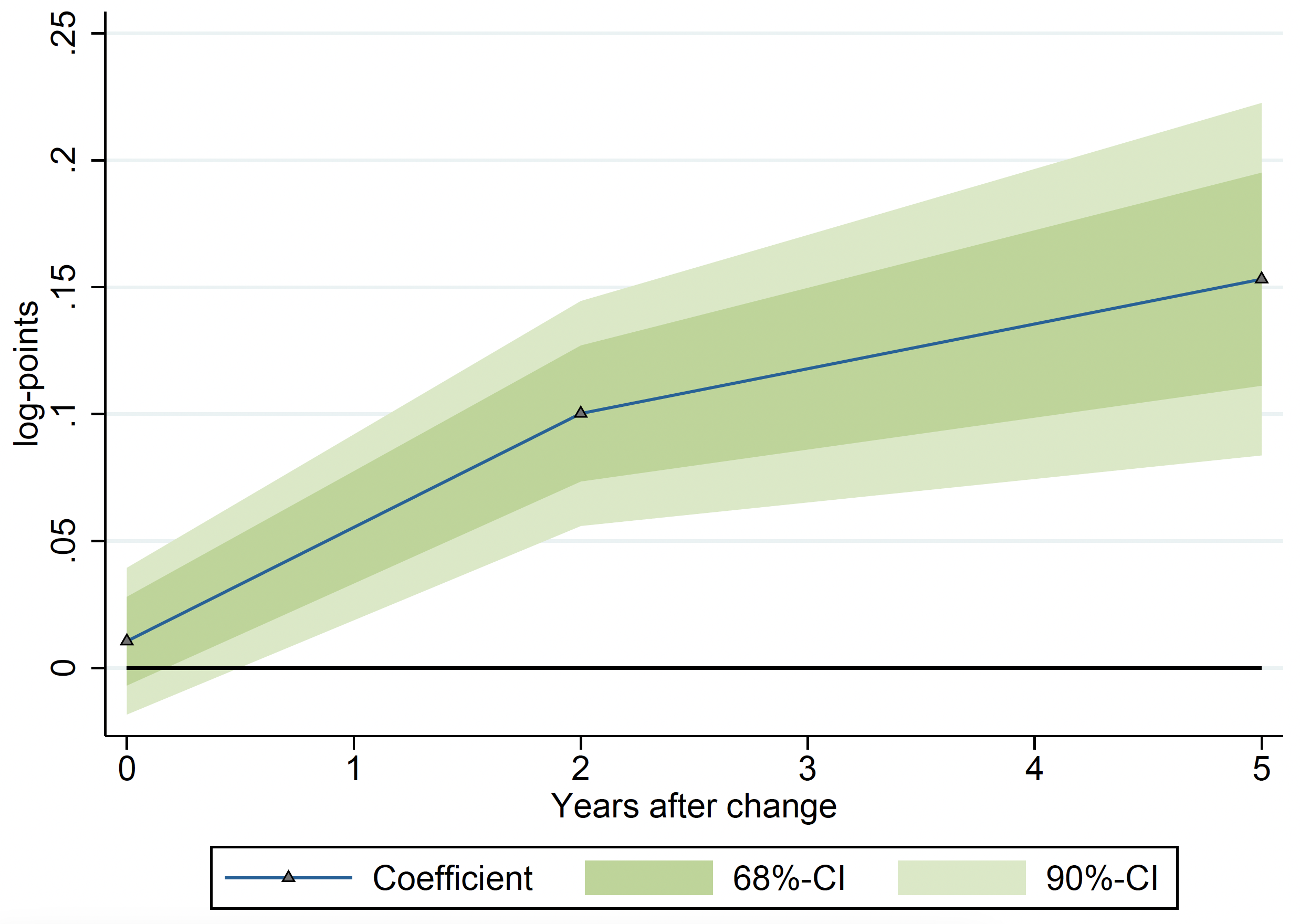

This result is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the positive estimated response of employment over time to an initial increase in productivity. The increasing curve indicates that the productivity impulse may take some time to take its full effect on employment. The estimated elasticity suggests that an initial increase of 10% in relative productivity is followed by a 1.5% increase in employment after five years.

This finding appears related to firms improving their position relative to competitors and attracting higher demand, with positive and persistent implications for sales and employment. These employment-generating dynamics seem to outweigh the potential negative effects related to higher efficiency and labour substitution (e.g. through automation). This is particularly true for firms that are initially less productive than their peers, whose employment is the most responsive to productivity growth.

As we further discuss in our paper, within-firm productivity growth is also positively related to wage growth, and further increases the probability of firm survival, thereby limiting job losses and the cost of separation associated with firm exit.

Figure 1 The firm-level link between productivity growth and employment growth: Impulse response

Note: This figure illustrates the results of a local projection impulse response regression estimation for the response of employment to a change in productivity using fixed effects for the country-industry-year. It leverages cross-country micro-aggregated data from the MultiProd project, using granular information at the level of a country, industry, year and position of firms in the productivity distribution at time t and t+j. The regressions are based on a sample including 22 SNA A38 industries within manufacturing and non-financial market services across nine countries (Belgium, Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Latvia, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden). Observations are weighted by the number of firms represented in the full population, normalised at the country level. Confidence bands are based on pointwise estimation of standard errors, clustered at the country-industry level.

Source: Calligaris et al. (2023).

Productivity growth is also positively linked to employment at the more aggregate level

At the more aggregate level, the role of reallocation and links across industries become more evident. In particular, job creation related to sales expansion for innovating firms can occur at the expense of competing firms, through market share reallocation and business stealing mechanisms (e.g. Harrison et al. 2014).

In line with this, we find that the link between productivity growth and changes in employment and wages at the industry level is weaker than the one at the firm level (but tends to remain positive). Increasing employment among expanding firms therefore tends to offset decreasing employment in shrinking or exiting firms. While other analyses have found negative own-industry implications of the adoption of labour-replacing technologies (e.g. Autor and Salomons 2016, Dauth et al. 2017), this evidence suggests that overall productivity growth is not detrimental to employment in the originating industry.

Our analysis additionally finds that productivity gains at the industry level contribute to stronger employment growth in downstream industries through domestic and global value chains. In other words, employment growth in a given industry is positively related to productivity growth in the supplier industries. The positive spillovers of productivity growth on labour demand are found to be also reflected in rising wages downstream, underscoring the role cross-industry linkages play in the diffusion of the benefits of productivity growth on labour markets. These spillovers may be related to a decrease in prices of the intermediate inputs associated with supplier productivity gains (Acemoglu et al. 2016).

Policy discussion

Overall, the evidence we present in Calligaris et al. (2023) suggests that boosting productivity is not a standalone economic objective; it also matters for labour demand. Indeed, productivity growth is on average accompanied by employment and wage growth across different levels of aggregation. As such, labour demand and productivity represent complementary rather than alternative policy targets. With this in mind, several policy areas can help ensure that workers benefit from productivity growth.

First, ensuring a level playing field, the contestability of markets, and reducing barriers to entry is key. This may enable the introduction of more radical innovations and foster post-entry growth, allowing new firms to scale up and contribute to employment growth. This appears particularly important also considering recent declines in business dynamism, increases in industry concentration and productivity divergence documented by OECD analyses (Calvino and Criscuolo 2019, Calvino et al. 2020, Bajgar et al. 2023).

Given that both productivity growth and related job creation and wage increases occur through creative destruction, it is key to maintain an environment in which reallocation of resources occurs, while paying attention to inclusiveness. To support the transition of workers who lose their jobs at shrinking or exiting firms to high-productivity ones, policies can support matching of job seekers to vacancies and training that allows workers to upskill and improve their employment prospects by coping with changes in skills demand (recent evidence focuses for instance on the demand for skills related to data analytics and AI; e.g. Borgonovi et al. 2023, Schmidt et al. 2023).

Boosting human capital by strengthening the quality of education systems, both focusing on STEM education and training and enhancing the capabilities of managers, may also accelerate technology diffusion. Lack of skills is indeed a frequently cited barrier to technology diffusion and productivity growth (Berlingieri et al. 2020, Criscuolo et al. 2021, Revoltella et al. 2023), which also depends on managers’ competence to recognise the need for technology adoption and complementary organisational changes and investments.

Finally, improving access to ICT and digital infrastructure appears key as these assets are important complements to many innovative technologies (Calvino and Fontanelli 2023). Supporting the creation of innovation networks and innovation ecosystems and providing incentives or support for R&D may foster innovation and develop firms’ absorptive capacities. Integration to resilient global and domestic value chains and connections to increasingly productive supplier industries may also be particularly beneficial for the economy, and restoring value chain links when these have been disrupted appears therefore relevant (Schwellnus et al. 2023).

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and cannot be attributed to the OECD or its member countries. Please see Calligaris et al. (2023) for additional details and notes.

References

Acemoglu, D, U Akcigit and W Kerr (2016) “Networks and macroeconomic shocks”, VoxEU.org, 30 January.

Acemoglu, D, C Lelarge and P Restrepo (2020), “Competing with Robots: Firm-Level Evidence from France”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 110: 383-388.

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2020), “The wrong kind of AI? Artificial intelligence and the future of labor demand”, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 13(1): 25-35.

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2017), “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from the US”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2016), “The race between machines and humans: Implications for growth, factor shares and jobs”, VoxEU.org, 5 July.

Aghion, P, C Antonin, X Jaravel and S Bunel (2020), “What Are the Labor and Product Market Effects of Automation? New Evidence from France”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14443.

Autor, D, F Levy and R Murnane (2003), “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4): 1279-1333.

Autor, D and A Salomons (2018), “Is automation labor-displacing? Productivity growth, employment, and the labor share”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 49(1) (Spring): 1-87.

Bajgar, M, G Berlingieri, S Calligaris, C Criscuolo and J Timmis (2023), “Industry concentration in Europe and North America”, Industrial and Corporate Change 00: 1-18.

Berlingieri, G, P Blanchenay, S Calligaris and C Criscuolo(2017), “The Multiprod project: A comprehensive overview”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2017/04.

Berlingieri, G, S Calligarisi, C Criscuoloi and R Verlhaci (2020), “Laggard firms, technology diffusion and its structural and policy determinants”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 86.

Borgonovi F, F Calvino, C Criscuolo, J Nania, J Nitschke, L O’Kane, L Samek and H Seitz (2023), “Tracking the skills behind the AI boom: Evidence from 14 OECD countries”, VoxEU.org, 20 Oct.

Calligaris, S, F Calvino, M Reinhard and R Verlhac (2023), "Is there a trade-off between productivity and employment?: A cross-country micro-to-macro study", OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 157.

Calvino, F and C Criscuolo (2019), “Business dynamics and digitalisation”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 62.

Calvino, F, C Criscuolo and R Verlhac (2020), “Declining business dynamism: Structural and policy determinants”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 94.

Calvino, F and L Fontanelli (2023), “Firms’ use of artificial intelligence: Cross-country evidence on business characteristics, asset complementarities, and productivity”, VoxEU.org, 14 June.

Nicoletti, G, P GAL, T Leidecker and C Criscuolo (2021), “The human side of productivity: Uncovering the role of skills and diversity for firm productivity”, VoxEU.org, 23 December.

Woessner, N, S Findeisen, J Südekum and W Dauth (2017), “The rise of robots in the German labour market”, VoxEU.org, 19 September.

Decker, R A, J Haltiwanger, R S Jarmin and J Miranda (2020), “Changing Business Dynamism and Productivity: Shocks versus Responsiveness”, American Economic Review 110(12): 3952-3990.

Graetz, G and G Michaels (2015), “Estimating the impact of robots on productivity and employment”, VoxEU.org, 18 March.

Harrison, R, J Jaumandreu, J Mairesse and B Peters (2014), “Does innovation stimulate employment? A firm-level analysis using comparable micro-data from four European countries”, International Journal of Industrial Organization 35: 29-43.

Koch, M, I Manuylov and M Smolka (2019), “Robots and Firms”, VoxEU.org, 1 July.

Revoltella, D, T Bending, and J Delanote (2023), “Corporate investment: Cyclical slowdown versus structural needs”, VoxEU.org, 13 October.

Schmidt, J, G Pilgrim and A Mourougane (2023), “The role of data skills in the modern labour market”, VoxEU.org, 12 October.

Schwellnus, C, A Haramboure and L Samek (2023), “Resilient global supply chains and implications for public policy”, VoxEU.org, 21 April.

Wooldridge, J (2009), “On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables”, Economic Letters 104(3): 112-114.