Automation technology is fundamentally changing the way in which we live and work. Machines are taking over tasks that were previously done by human workers. But new jobs are also created, so what is the net effect of automation on employment? So far, we have mixed evidence. For example, Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) report negative effects, whereas Autor et al. (2015) and Graetz and Michaels (2015) find no effect. Gregory et al. (2016) suggest there is a positive impact.

This disagreement might be due to the difficulty of measuring automation technology. The literature uses proxies, such as the share of a job that consists of routine tasks (following Autor et al. 2003), or the use of computers at the workplace and investment in robots and computers. Ideally, it would be better to measure automation technology directly as the outcome of an innovative process.

This is what we do in a new paper using patents (Mann and Püttmann 2017). We apply a machine learning algorithm to all US patents granted between 1976 and 2014, and identify the patents related to automation. Our classification is comprehensive, as it includes both physical inventions (such as robots) and cognitive inventions (such as software and processes).

By assigning the patents to the industries where they are likely to be used, and to the regions where these industries are represented, we create an annual measure of new automation technology at the level of US commuting zones. In our empirical strategy, we make use of the fact that we measure innovation at the national level, and employment effects at the level of local labour markets. We find that automation has positive net employment effects.

A new measure of automation

Patents are a natural candidate for measuring technological advances. But while they are often used as proxies for innovative activity, they have rarely been interpreted as indicators of new technology available to firms – even though Griliches had recommended this as far back as 1990. This is what we attempt to do.

We take the texts of all 5 million patents granted in the US between 1976 and 2014, and sort them into automation and non-automation patents. We manually classify 560 patents using the following definition:

An automation patent describes a device that operates independently from human intervention and fulfils a task with reasonable completion.

Based on this sample, we train a machine learning algorithm to find automation patents drawing on a dictionary of several hundred word stems. Patent texts are written in a standardised, matter-of-fact language, which makes them well suited for text classification.

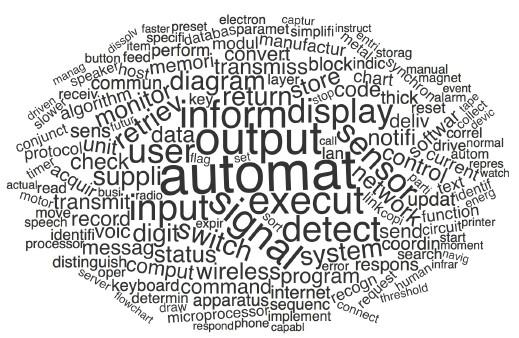

The most important tokens are 'automat' and 'output' (see Figure 1). While these are fairly general, the algorithm also puts weight on more specific engineering terms such as 'microprocessor' or 'motor' and action verbs like 'detect' and 'execut'.

Figure 1 Words that indicate an automation patent

Source: USPTO, Google and own calculations.

Notes: Token size is proportional to the value of the mutual information criterion in a sample of 560 classified patents. We show only the 150 highest-ranked tokens, excluding chemical and pharmaceutical words.

Figure 2 shows the number of automation patents over time. We identify 2 million automation patents out of a total of 5 million. We find a rapid increase in the number of automation patents, from 70,000 in 1976 to 180,000 in 2014. Automation technology is clearly on the rise: in this period, the relative share of patents related to automation increased from 25% to 67%.

Figure 2 Automation patents, 1976-2014

Source: USPTO, Google and own calculations.

Note: Shows all utility patents, classified as described in text and paper.

Next, we link the patents to the industries in which they are likely to be used, drawing on Silverman (2002). These industries may be different from the industry of the inventor. For example, Microsoft might hold a patent on spreadsheet software that can be used in finance. Our resulting industry-level indicator confirms that, in line with the theories of routine-biased technological change, more automation patents can be applied in industries that had a high share of routine tasks in 1960. The link between routine-task intensity and automation, however, has grown weaker over time. This might be a sign that routine jobs have already largely been replaced, but it could also mean that automation technology has evolved to carry out non-routine tasks too.

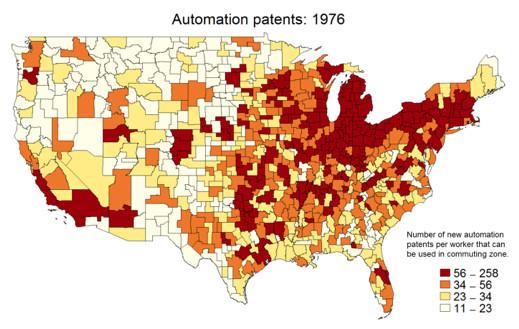

We identify in which US commuting zones the industries that can use automation technology are located. This allows us to calculate how many new automation patents that individual workers in a commuting zone could potentially use. The resulting dataset shows a striking pattern. Figure 2 maps the automation indicator for 1976 and for 2014 (the differences between these two years are characteristic of the trend over the whole sample). In the 1970s and 1980s, new automation technology was concentrated in the Great Lakes area, which had a high share of manufacturing employment. By 2014, the areas where automation technology can be used have become more dispersed, a result of both the evolving nature of automation, and changes in local industry structure.

Figure 3 Intensity of automation patents across commuting zones

Source: USPTO, Google, Silverman (2002), County Business Patterns and own calculations.

Employment effects of automation

We analyse the effect of automation technology on employment across 722 US commuting zones, over 39 years. We examine local economic outcomes of national patenting activity, in the spirit of Bartik (1991). This approach has the advantage that outcomes in local industries are unlikely to significantly affect national patenting. This suggests that most of the employment changes we measure should be due to advances in the available technology, rather than the other way around.

We regress five-year changes in the employment-to-population ratio on our five-year cumulated automation indicator. We use several controls, among them non-automation patents and demographic variables. We find:

- More automation delivers more employment. More patents in a commuting zone leads to an increase in the employment-to-population ratio. A one-standard-deviation increase of our automation measure predicts a rise of a fifth of a percentage point in the employment-to-population-ratio per five-year period.

- Weaker positive effects where more jobs are routine. The employment effect of automation is weaker in areas with a high initial share of routine labour, but remains positive.

- Bad news if you work in a factory, good news if you want a service job. Manufacturing employment falls and service sector employment grows in response to new automation technology. In manufacturing, commuting zones with a high routine task share fare worse, whereas in the service sector, the interaction of the automation index with the routine task share is insignificant.

Our assessment of automation is more positive than most other research – automation, measured comprehensively and granularly through patents, has a benign effect on employment. Our analysis can be reconciled with previous findings. Routine jobs benefit less from automation, and manufacturing jobs (where more robots are used) tend to do worse. But this has been more than compensated by a rise in service jobs.

References

Acemoglu, D and P Restrepo (2017), "Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets", NBER Working Paper No.23285.

Autor D H, D Dorn and G H Hanson (2015), “Untangling Trade and Technology: Evidence from Local Labor Markets”, The Economic Journal 125(584): 621-646.

Autor, D H, H Levy and R J Murnane (2003), “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4): 1279-1333.

Bartik, T J (1991), Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies? Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Graetz, G and G Michaels (2015), “Robots at Work”. CEPR Discussion Paper 1335.

Gregory, T, A Salomons, and U Zierahn (2016), “Racing with or Against the Machine? Evidence from Europe”, ZEW Discussion Paper No.16-053.

Griliches, Z (1990), “Patent Statistics as Economic Indicators: A Survey”, Journal of Economic Literature 28: 1661-1707.

Mann, K and L Püttmann (2017), "Benign Effects of Automation: New Evidence from Patent Texts", Unpublished manuscript.

Silverman, B S (2002), Technological Resources and the Logic of Corporate Diversification, Routledge.