For decades, but especially over the last 20 years, scientists of all kinds have been asking the same question, “Why are people nice to each other when it appears to violate their self interest?” That people should behave selfishly seems to follow sensibly from notions of self-preservation from evolutionary biology. Altruistic behaviour, on the other hand, needs some explaining.

Theories of altruistic behaviour typically link self-interest, broadly construed, with altruism. These include survival of one’s genes (kin selection, see Hamilton 1964), physical survival (norm adherence through sanctions, Boyd and Richarson 1992), and material benefit (mutualistic reciprocity, Trivers 1971).

These theories provide a sound backbone for the existence of altruistic behaviour in the human psyche. In economic laboratory studies, subjects exhibit significant levels of altruistic giving and inequity aversion (Fehr and Schmidt 1999, Bolton and Ockenfels 2000, Andreoni and Miller 2002). Outside the laboratory however, we encounter vast amounts of poverty and inequality and yet charitable giving is only a tiny fraction of income worldwide (Andreoni 2006). How can we reconcile a distaste for inequality with behaviour that indicates people actually tolerate a great deal of it?

Communication and altruism

In a recent paper (Andreoni and Rao 2010), we start with the observation that altruistic acts are typically also social acts, and this social nature of the interaction allows for the underlying mechanisms of altruism to function. We propose that these social cues have evolved so that altruistic behaviour is not expressed indiscriminately, but rather is likely to be expressed when it is instrumental in serving other (perhaps selfish) ends.

To test this hypothesis, we use a subtle manipulation of a single social factor, i.e. verbal communication. Communication is a natural social cue because it is typically the link between giver and receiver. Indeed the leading theory on the origins of verbal communication is that it arose out of gestural communication to facilitate mutually beneficial coordinative acts (Grice 1957). In support of this theory, Tomasello (2008) shows that the differences in altruism between great apes and humans can be linked to humans’ advanced social capacities, including verbal communication and forming beliefs about another’s thinking.

Experiment and results

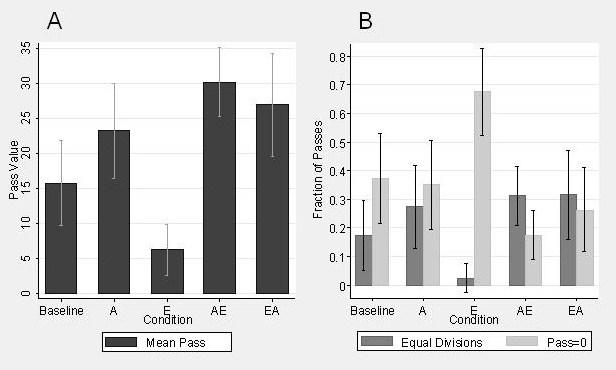

Our study used an experimental economics workhorse, the Dictator Game, in which two players split a sum of money (here $10). One player is the “allocator”, the person who divides the pie, and other is the “receiver”, who has no control over the division. In Experiment 1, we systematically altered who in the pair (one, both, and the order) could send a written message and numerical request. The results are presented in Figure 1. We find that in the condition in which only the allocator could speak, only 6% of the endowment was donated, which was significantly lower than the no-communication baseline of 15%. This is the condition in which roles were most asymmetric in the social interaction. In stark contrast, any time the recipient spoke, at least 24% of the endowment was passed – asking is indeed powerful. There were three conditions in which the allocator spoke: Explain (only allocator), Ask-Explain (receiver asks then allocator responds) and Explain-Ask (allocator sends proposed division with verbal message, receiver responds). Giving was 4 times lower in Explain as compared to the two-way communication conditions. Clearly explaining in the face of an “ask”, regardless of the order of communication, was fundamentally different than when the receiver had to remain silent.

Figure 1. Pass values by condition of Experiment 1 (Baseline: no communication, A: receiver “ask” alone, E: allocator “explain” alone, AE: “ask” then “explain”, EA: “explain” then “ask”.

To understand communicative intent, we performed textual content analysis. Fairness was 5-6 times more likely to be spoken about in the presence of an ask, whereas remorse was one-quarter as likely. Interestingly, the content did not depend on whether the allocator was responding directly to an ask, or sending a message knowing they would receive a reply (“anticipating the ask”).

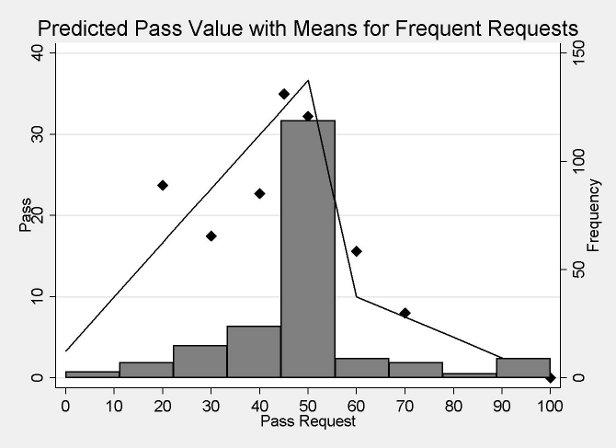

The results lead to a puzzle. First, the ask content is quite obvious. One would guess that most people request an equal division and focus on fairness. Figure 2 shows this is precisely the case. Despite the obviousness, asking still has a significant impact on behaviour. Second, the effect of explaining flips sign in the presence of an ask. Saying “sorry” no longer seems to be an option. Communication from recipients, regardless of the order of who spoke, led to a “conversation” more likely to be centred on fairness.

Figure 2. Distribution of requests (right y-axis) along with fitted pass values (left y-axis).

We hypothesised that communication from the receiver led the allocator to think more fully about the receiver’s position, and this served to block self-serving behaviour. To test this hypothesis, in Experiment 2 all subjects made decisions for each role before we determined which role would count for monetary payoffs – they made one written request as receiver, and one allocation and written message as allocator. Then roles were determined with a coin-flip. In the condition in which only the allocator could speak (similar to Explain from Experiment 1), the allocations and verbal content appeared as if recipients had been able to ask. Our interpretation is that asking leads the allocator to actively consider and identify with the role of the recipient. We call this feeling “empathy.”

What about “appearances”

At the outset we posed the question, “Why are people nice to each other when it appears to violate self-interest?” The idea behind “impure altruism” is that there are selfishly motivated reasons driving most giving (Andreoni 1990). We find that communication seems to make people think more about others, a form of empathy, and this leads to more giving. But does it enhance a genuine concern for others? Two channels of impure altruism are relevant here: self-signalling (Bodner and Prelec 2003) and guilt aversion (Dufwenberg and Gneezy 2000).

A self-signaller is selfish but wants to believe that she is not (“selfishly ignorant”). In the Experiment 1 conditions with an “ask”, we can compare choices when the allocator simply has the potential to know the recipient’s feelings (baseline) to one in which she is forced, based on the belief formation associated with verbal communication, to actually consider her. The argument for self-signalling asserts that this knowledge raises the cost of self-deception.

Guilt aversion proffers that people don’t want to fall short of others’ expectations. Guilt aversion can explain the results if empathy limits the effectiveness of strategies to reduce guilt. For instance, it may be easier to trick oneself into believing the other is not expecting much when you do not consider her position.

In Experiment 2, many subjects found it difficult to simultaneously request a fair division and administer a stingy one. Under the guilt aversion explanation, this is because taking receiver’s position generates a high pass expectation and passes rise with this “guilt threshold.” Under self-signalling, the difficulty occurs because being placed in both roles unveils self-deception (now one knows that he would not consider it acceptable to pass 0).

Whether communication enhances genuine empathy or merely increases knowledge of the other so that guilt reducing strategies or self-deception are more costly is not testable with our data. More generally, it is possible that what people often refer to as empathy is not the genuine article. These are interesting questions that we hope to address in future research.

References

Andreoni, J. (1990), “Impure altruism and donations to public goods: a theory of warm-glow giving”, Economic Journal, 100:464-477.

Andreoni, J (2006), “Philanthropy”, in S Kolm and J M Ythier (eds.), Handbook on the Economics of Giving, Reciprocity and Altruism, 1201-1269, Elsevier.

Andreoni, J and JH Miller (2002), “Giving according to GARP: An experimental test of the consistency of preferences for altruism”, Econometrica, 70:737-753.

Andreoni, J and JM Rao (2010), “The power of asking: How communication affects selfishness, empathy and altruism”, NBER Working Paper 16373. Forthcoming in Journal of Public Economics.

Bodner, R and D Prelec (2003), “The diagnostic value of actions in a self-signaling model”, in I Brocas and J Carillo (eds.), The Psychology of Economic Decisions, vol. Rationality and Well-being, volume 1, Oxford University Press.

Bolton, G and A Ockenfels (2000), “ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition”, The American Economic Review, 90(1):166-193.

Boyd, R and PJ Richerson (1992), “Punishment allows the evolution of cooperation (or anything else) in sizable groups”, Ethol Sociobiology, 13:171-195.

Dufwenberg, M and U Gneezy (2000), “Efficiency, reciprocity, and expectations in an experimental game”, Games and Economic Behaviour, 30:163-182.

Fehr, E and K Schmidt (1999), “A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3):817-868.

Hamilton, W (1964), “The genetical evolution of social behaviour”, Journal of Theoretical Biology,7(1):1.

Grice, H (1957), “Meaning”, The Philosophical Review : 377-388.

Trivers, R (1971), “The evolution of reciprocal altruism”, The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1):35.

Tomasello, M (2008), Origins of Human Communication, MIT Press.