The chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, recently stated that “[t]he biggest surprise in the US economy this year has been inflation” (Yellen 2017). The Federal Reserve expected that the rapid decline in unemployment – from 4.8% in January to 4.2% in September, below the Federal Reserve’s estimate of the natural rate of unemployment – would have led to an increase in inflation. Yet, core inflation declined from 1.9% to 1.3% during that period. The recent World Economic Outlook (IMF 2017) documents that the insensitivity of inflation to slack is pervasive across the developed world.

Download the 19th Geneva Report on the World Economy, And Yet It Moves: Inflation and the Great Recession, here

Listen to two of the authors discuss the report in an interview for Vox Talks here

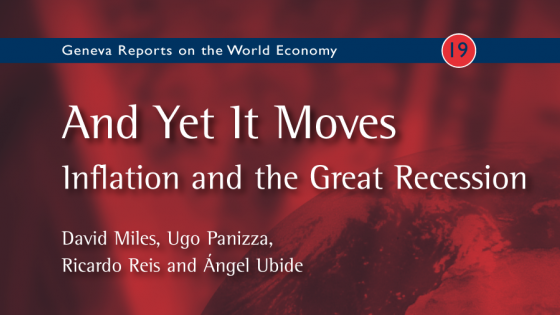

This puzzling behaviour of inflation could be dismissed as a fluke, an example of the ‘errors’ in the measurement of economic data and in the predictions from economic models. However, the puzzle has lasted for much longer than just the last ten months. Figure 1 shows a measure of pure inflation – the change in prices that is a proportional across all goods and services, independent of changes in relative prices – for the US and Eurozone using an estimator developed by Reis and Watson (2010). In the wake of the biggest recession since the Great Depression, it is surprising how stable pure inflation has been.

Figure 1 Pure inflation in the US and the Eurozone

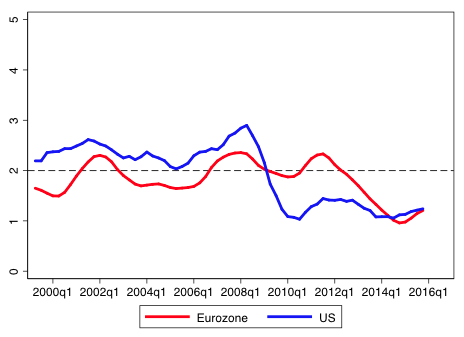

Figure 2 shows a simpler estimator of pure inflation, core inflation, which has also been low and relatively stable, albeit below the 2% target in most countries.

Figure 2 Inflation in advanced economies

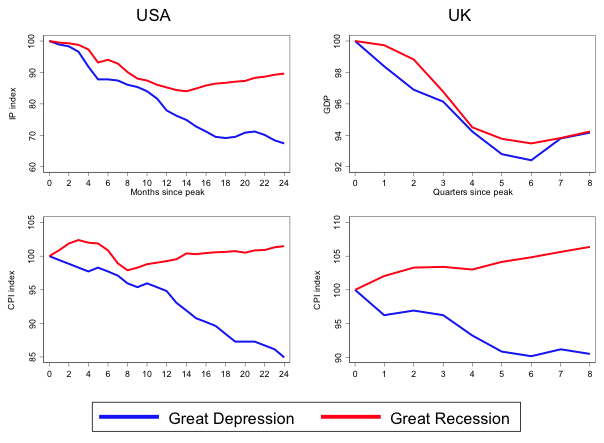

This is remarkable. The shocks that have hit the developed economies during the last decade have been large and of diverse nature. There was a deep downturn in real activity, as severe as the downturn at the onset of the Great Depression of the 1930s (Figure 3). And yet, while the Great Depression led to deflation, pure inflation over the past ten years has remained close to 2%, and even headline inflation went into negative territory for only a brief period (Japan is the exception). After 2010, real activity bounced back and unemployment declined rapidly to historically low levels in the US and the UK, reducing economic slack. Moreover, in the past decade, commodity prices went through a rollercoaster, first rising to unprecedented heights, and then sharply falling. To those used to looking at inflation from the perspective of ‘demand-pull’ or ‘cost-push’ shocks through a Phillips curve, the stability of inflation in the face of such volatile environment is mysterious.

Figure 3 Prices and economic activity during the Great Recession and the Great Depression

Further, real interest rates trended downwards, with no corresponding movement in inflation. Nominal interest rates were pegged close to zero, yet the economy did not enter an inflationary spiral or a deflationary spiral. The monetary base increased by an order of magnitude and the velocity of M2 bounced up and down. Public debt in many developed countries rose to peacetime records, and various, large-scale unconventional policies were adopted and refined over time. All point to many, large, and varied shocks hitting inflation. And yet, inflation was stable and low.

We study these multiple shocks, and different theories of inflation to interpret them, in the 19th Geneva Report on the World Economy (Miles et al. 2017). The conclusion is that some way, somehow, multiple shocks summed up to little, with a relatively small but persistent shift down in inflation with little change in volatility. As regards inflation over the past ten years, we were lucky – and even so it took a range of bold actions from central banks. Next time we may not be so lucky. Taking away the ability of central banks to act boldly would be a very bad idea.

Good luck or good policies?

Since most societies regard stable inflation as a goal, it is tempting to describe this solid anchoring of inflation as a great achievement of monetary policy. Facing a series of shocks, central banks reacted with an arsenal of policy measures, generating their own shocks to ensure that the sum was close to zero. Given the severity of the financial crisis, the scale of the subsequent recession, the prolonged disruption in the supply of credit, and the high volatility in commodity prices, for inflation in nearly all developed countries to barely go negative and to stay only a few decimal points below target is a surprisingly good outcome. If inflation had stayed negative for a more significant period, perhaps we could have entered a downward deflationary spiral turning a bad recession into a deep depression.

At the same time, central banks were lucky. When deflation risks were at their highest – in 2009 and into 2010 – the strength of commodity prices kept inflation transitorily higher. Widespread downward nominal rigidities prevented deflation in spite of the rise in slack during the recession. Expectations and credibility stayed high event though central banks engaged in a great deal of policy experimentation. Perhaps it was monetary policy itself that allowed for each of these favourable factors to be present, but luck likely also played a role.

Not an unambiguous success

Many good policies were pursued during this time to stabilise inflation, but some central banks were reluctant to embrace the symmetry inherent to flexible inflation targets. Looking back, slack was mis-measured and the possibility of hysteresis was underestimated, while the increasing focus on financial stability conflicted at times with the preservation of price stability.

As a consequence, the outcome was not an unambiguous success. Market-based measures of inflation expectations have declined, and inflation has been persistently below target. Perhaps this is due to temporary shocks, but it is also possible that underlying inflation has permanently shifted lower in the post crisis period. Stable inflation somewhat below 2% looks impressive from an historical perspective. However, from the perspective of price stability, defined as inflation at 2% over the medium term, central banks were unable to reach their target. Below target inflation with low policy rates is a source of worry if this implies that, when the next recession hits, policymakers will have less room to lower real interest rates and cushion the shock.

The future

The young, or those with short memories, could be forgiven for looking condescendingly at their older friends who speak of inflation as a major economic problem. Inflation appears well anchored but, like Galileo Galilei told his contemporaries who thought the Earth was immovable, “Eppur si muove” (“and yet it moves”). What if the anchoring was just luck? Will the great anchoring soon be followed by a great bout of inflation, or by a descent into deflation, just as the Great Moderation was followed by the Great Recession? What policy developments cause bring worries for the future?

An important source of concern is whether central bank independence is seriously under threat. If it is, and if central banks lose the ability to pursue inflation targets without political interference, it is possible that the next 20 years be the opposite of the last 20 years – a period when inflation has been low and stable and (recently) with inflation undershooting targets. A large central bank balance sheet is consistent with efficient credit allocation, it is desirable for monetary implementation and the provision of liquidity, and perhaps it is even necessary for stabilising credit conditions by allowing commercial banks to rely less on interbank flows (which proved unreliable in stressed circumstances). Yet, some politicians may perceive it as an overreach of central banks with scope to make losses and to direct credit in a way that is not subject to much outside control. To guard the independence of the central banks, more frequent revisions to their mandates and a further push towards transparency and accountability seems inevitable and desirable.

All in all, central banks achieved something which was not guaranteed in the aftermath of the financial crash and which, at the start of 2010, seemed very far from likely – stable, low, positive inflation. This is not a source for complacency, as part of this good outcome was due to luck. The dice fell in a good way after the financial crash. That good luck was not squandered with poor polices should be a reason to celebrate. But we cannot expect such luck every time. The challenge of stabilising inflation is likely to return.

We should not expect too much of central banks; but, more importantly, we should not restrict their tools to handle whatever the next roll of the dice brings.

References

IMF (2017), World Economic Outlook, Seeking Sustainable Growth, Washington DC.

Miles, D, U Panizza, R Reis and A Ubide (2017) And Yet It Moves: Inflation and the Great Recession, 19th Geneva Report on the World Economy, ICMB and CEPR.

Reis, R and M Watson (2010) “Relative Goods’ Prices, Pure Inflation, and the Phillips Correlation”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2(3): 128-157.

Yellen, J (2017) “The U.S. Economy and Monetary Policy”, speech delivered at the Group of 30 International Banking Seminar, 15th October, Washington, DC.