Scholarly work on the currency used in international transactions distinguishes two views. One, familiar to economists, emphasises pecuniary motives. Safety, liquidity, network effects, trade links, and financial connections explain why some currencies are used disproportionally as a medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account by governments and private entities engaged in cross-border transactions (Frankel 2008). We refer to this as the ‘Mercury hypothesis’.1

Another view, due to political economists and applied mainly to the choice of reserve currency or currencies, emphasises strategic, diplomatic, and military power. Insofar as a country has such power, foreign governments will see it as in their geopolitical interest to conduct their cross-border transactions using its currency. That leading power for its part will possess political leverage with which to encourage the practice (e.g. Kindleberger 1970, Strange 1971, 1988, Kirshner 1995, Williamson 2012, Cohen 1998, 2015, Liao and McDowell 2016). In other words, international currency choice is from Mars rather than Mercury.2

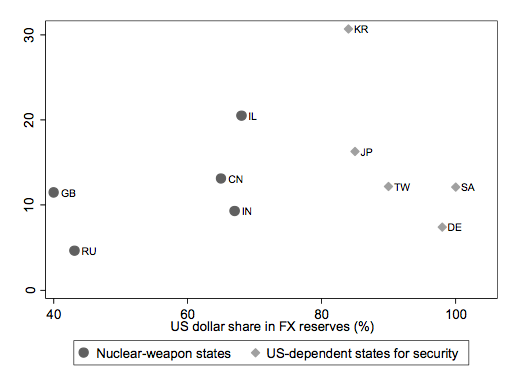

When added to the intellectual portfolio of economists, this second hypothesis helps to explain some otherwise perplexing aspects of the currency composition of international reserves. It helps to explain why Japan holds a larger share of its foreign reserves in dollars than China. It helps to explain why Saudi Arabia holds the bulk of its reserves in dollars, unlike another oil exporter, Russia. It helps to explain why Germany holds virtually all of its official reserves in dollars, unlike France. Germany, Japan and Saudi Arabia all depend on the US for security. China, Russia, and France, on the other hand, possess their own nuclear weapons as deterrents. Comparing nuclear-weapon states and states dependent on the US for their security, as in Figure 1, suggests that the difference in the share of the US dollar in foreign reserve holdings is on the order of 35 percentage points.

Figure 1 Share of the US dollar in the foreign reserves of selected countries in the modern era

Note: The figure plots publicly available estimates of the share of the US dollar in the foreign exchange reserves of nuclear-weapon states (dark grey dot) and US-dependent states for security (light grey diamond) against the share of the US in the trade in goods (exports and imports) of the countries in question. GB: United Kingdom (estimate for 2004); RU: Russia (estimate for 2016); CN: China (estimate for 2008); IL: Israel (estimate for 2015); IN: India (estimate for 2015); JP: Japan (estimate for 2006); KR: Korea (estimate for 1987); TW: Taiwan (estimate for 2016); SA: Saudi Arabia (guesstimate for 2016); DE: Germany (estimate for 2004). France is not reported due to lack of data.

Mars and Mercury in orbit

In a recent study (Eichengreen et al. 2017), we test the Mars and Mercury hypotheses using data (based on Lindert 1967) on the foreign exchange reserves of 19 countries before WWI, when the currency composition of reserves was known and security alliances proliferated. We find that military alliances boost the share of a currency in the partner’s foreign exchange reserve portfolio by close to 30 percentage points.

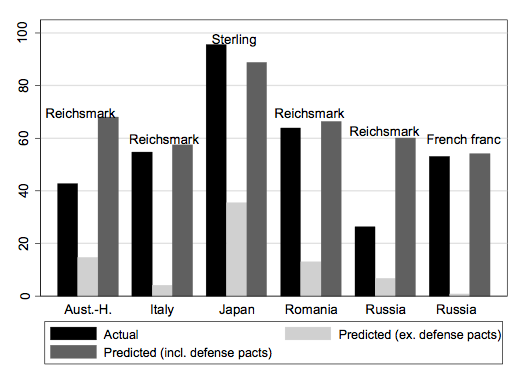

Figure 2 shows the predicted shares of the main reserve currencies in the foreign reserve holdings of five countries that signed defence pacts with the issuers prior to WWI. Predicted shares including the effects of defence pacts are shown as dark grey bars, while those excluding the effects of defence pacts are shown as light grey bars. Actual currency shares are shown as black bars. Predicted shares are clearly much closer when the model includes defence-pact effects.

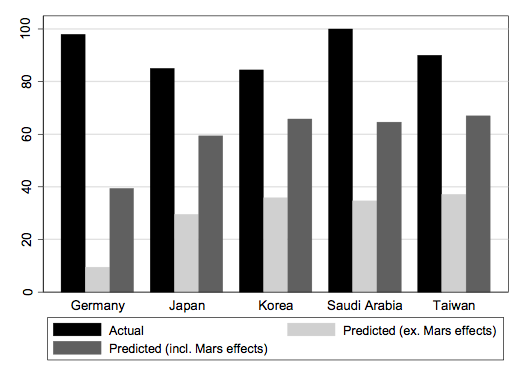

Figure 3 illustrates the point with reference to five countries that depend on the US for their security (Germany, Japan, Korea, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan) in the modern era using our estimate of the geopolitical premium obtained for the earlier era. The Mars hypothesis again goes a long way toward explaining the dominance of the US dollar in reserves.

Figure 2 Importance of geopolitical versus pecuniary factors in reserve currency choice

Then

Note: The figure shows the predicted shares of selected reserve currencies in the foreign reserve holdings of five countries which had signed a defence pact with the issuer of the currencies in question prior to WWI. Predicted shares are computed under two scenarios using our model estimates (i) including the effects of defence pacts (shown as dark grey bars) and (ii) excluding the effects of defence pacts (shown as light grey bars). Actual currency shares are shown as black bars.

Figure 3 Importance of geopolitical versus pecuniary factors in reserve currency choice

Now

Note: The figure shows the predicted shares of the US dollar in the foreign reserve holdings of five countries which depend on the US for their security now. Predicted shares are computed under two scenarios using our model estimates (i) including the effects of military alliances (shown as dark grey bars) and (ii) excluding the effects of military alliances (shown as light grey bars). Actual currency shares are shown as black bars.

US first policies

The dollar’s international currency status allows the US government to place dollar-denominated securities at a lower cost because demand from major reserve holders is stronger than otherwise. The cost to the US of financing budget and current account deficits is correspondingly less.

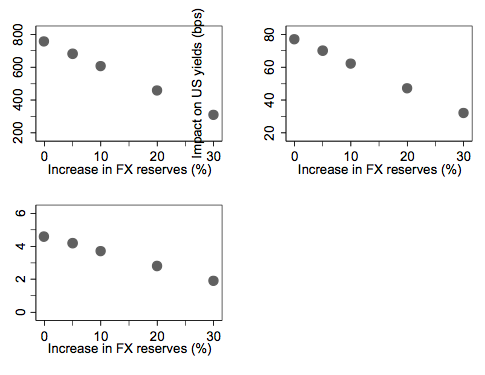

But if that role were seen as less sure and that security guarantee as less iron clad, because the US was disengaging from global geopolitics in favour of more stand-alone, inward-looking policies, the security premium enjoyed by the US dollar could diminish. In a scenario where the US withdraws from the global stage and the dollar’s security premium disappears, while the level of global reserves remains unchanged, the result is a 30 percentage point reduction in the share of the US unit in the reserves of US-dependent states, and an increase in the share of other reserve units such as the euro, yen and renminbi. Our estimates imply that $750 billion worth of official US dollar-denominated assets – equivalent to 5% of US marketable public debt – would be liquidated, while long-term US interest rates would increase by as much as 80 basis points (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Impact on financial markets of loss of US dollar’s security premium

Note: The figure shows estimates of the impact on bond and exchange markets of hypothetical scenarios which assume that the US withdraws from the world and the US dollar loses its geopolitical/security premium, hence leading to a change in the composition of global foreign exchange reserves. The scenarios further assume that the level of the reserves in question increases by up to 30%. The top left-hand side chart shows the estimated amount of US dollars to be liquidated conditional on the hypothesized increase in global foreign exchange reserves. The top right-hand side chart shows the estimated increase in long-term US interest rates conditional on the hypothesized increase in global foreign exchange reserves. The bottom left-hand side chart shows the estimated US dollar depreciation conditional on the hypothesized increase in global foreign exchange reserves.

Implications

Our findings thus speak to current discussions on the future of the international monetary system, amidst concerns about possible US disengagement from the global geopolitics in favour of a more US-first, isolationist role. They also suggest that China’s growing self-confidence and assertiveness on the international stage could help to support the emergence of the renminbi as an increasingly important international unit. And they suggest that deeper European cooperation in domains such as external security and defence is not irrelevant for the euro’s global standing.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB) or the Eurosystem. They are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB or the Eurosystem.

References

Cohen, B (1998), The Geography of Money, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Cohen, B (2015), Currency Power: Understanding Monetary Rivalry, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Eichengreen, B, A Mehl and L Chiţu (2017), “Mars or Mercury? The Geopolitics of International Currency Choice”, NBER Working Paper, forthcoming.

Frankel, J (2008), “The Euro Could Surpass the Dollar within Ten Years,” VoxEU.org, 18 March.

Gray, J (1992), Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, Harper Collins.

Kagan, R (2002), “Power and Weakness” Policy Review 113 (June/July).

Kindleberger, C (1970), Power and Money: The Politics of International Economics and the Economics of International Politics, New York: Basic Books.

Kirshner, J (1995), Currency and Coercion: The Political Economy of International Monetary Power, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Liao, S and D McDowell (2016), “No Reservations: International Order and Demand for the Renminbi as a Reserve Currency,” International Studies Quarterly 60: 272-293

Lindert, P (1967), “Key Currencies and the Gold Exchange Standard, 1900-1913”, PhD dissertation, Cornell University, Ithaca.

Posen, A (2008), “Why the Euro will Not Rival the Dollar,” International Finance 11: 75-100.

Strange, S (1971), Sterling and British Policy, London: Oxford University Press.

Strange, S (1988), States and Markets, London: Pinter.

Williamson, J (2012), “Currencies of Power and the Power of Currencies: The Geo-Politics of Currencies, Reserves and the Global Financial System,” unpublished manuscript, Washington, DC: International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Endnotes

[1] In ancient Roman religion and myth, Mercury was the god of commerce while Mars, which we discuss below, was the god of war.

[2] Courtesy of John Gray’s book, Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus (Gray 1992) and Robert Kagan’s phrase “Americans are from Mars, Europeans are from Venus” (Kagan 2002). See also Posen (2008).