Two years after the most severe global financial crisis in decades, financial markets are flush with liquidity, aided by ample monetary stimulus from central banks around the world. Emerging market economies are experiencing large inflows of capital that drive up their exchange rates and inflate asset prices.

Policymakers in the affected economies are justifiably worried about the consequences. Indeed, as Reinhart and Reinhart (2008) have pointed out, such “capital flow bonanzas” are all too often followed by severe crashes that impose massive social costs. A growing chorus of academics, perhaps most famously represented by Stiglitz (2002), has argued that capital flows to emerging markets should therefore be regulated. Country after country, from Brazil to Indonesia, Korea, Peru, Taiwan and Thailand, has followed their advice in recent months. In a notable reversal on earlier policies, the IMF has given its blessing to capital controls under certain circumstances (Ostry et al. 2010).

Externalities of capital flows

In a recent research paper (Korinek 2010b), I make the welfare theoretic case for regulating capital flows based on the notion that such flows impose externalities on the recipient countries. Just as environmental pollution produces externalities that reduce societal wellbeing if unregulated, capital inflows to emerging markets produce externalities that make such economies more prone to financial instability and crises. By implication policymakers can make everybody better off (i.e. achieve a Pareto-improvement) by regulating and discouraging the use of risky forms of external finance, in particular of foreign currency-denominated debts.

Risky forms of capital inflows create externalities because individual borrowers find it optimal to ignore the effects of their financing decisions on aggregate financial stability. They take the risk of financial crisis in their economy as given and do not recognise that their individual actions contribute to this risk. In a way they face a “prisoners’ dilemma”; if they could all agree to use less risky financing instruments and less external finance overall, the economy as a whole would become more stable and everybody would be better off. This creates a natural role for policy intervention.

Mechanism of financial crises

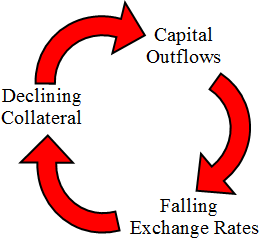

The economic rationale for capital flow regulations derives from a specific market imperfection that plays a crucial role during emerging market financial crises. International investors typically demand explicit or implicit collateral when providing finance. However, the value of most of a country’s collateral depends on exchange rates. When an emerging economy is hit by an adverse economic shock, its exchange rate depreciates, the value of its domestic collateral declines, and international investors become reluctant to roll over their debts. The resulting capital outflows depreciate the exchange rate even further and trigger an adverse feedback cycle of declining collateral values, capital outflows, and falling exchange rates (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Feedback loops during emerging market crises

This financial feedback loop, sometimes referred to as Fisherian debt deflation or simply as deleveraging cycle, can amplify economic shocks so that a relatively small initial shock leads to large declines in exchange rates, borrowing capacity and economic activity coupled with large capital outflows (see e.g. Mendoza, 2006). As shown in Korinek (2010b), rational private agents do not internalise their contribution to such feedback loops and therefore impose externalities on the rest of the economy.

Magnitude of externalities

Our theory of externalities based on financial vulnerabilities provides a clear framework to determine the optimal magnitude of policy measures. The reason why capital inflows expose an economy to financial fragility is that they may reverse precisely when the economy is experiencing financial difficulty and trigger the described feedback loops.

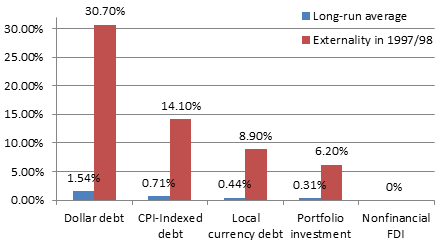

Different forms of capital inflows result in different probabilities of future capital outflows with different payoff characteristics in the event of a crisis, which in turn leads to different externalities. Optimal macro prudential policy should aim to precisely offset these externalities.

If an emerging economy takes on dollar debts and subsequently experiences a financial crisis, the exchange rate depreciates and the domestic value of the debt increases sharply, implying that dollar debt imposes a large negative externality. CPI-indexed debt protects borrowers against the risk of exchange rate fluctuations, imposing smaller externalities. Local currency debts and portfolio investments play an insurance role, since the value of the local currency and equity markets tend to go down during crises. Finally, non-financial foreign direct investment often stays in the country when a financial crisis hits; in those instances it does not impose any externalities.

In Figure 2, we report a sample estimation of the annual magnitude of externalities created by various types of capital inflows to Indonesia (see Korinek 2010b for a detailed description of the analytical method employed). For each type of capital flows, the blue bar to the left represents the average magnitude of externalities over the past two decades, whereas the red bar on the right captures the externalities imposed during the 1997/98 financial crisis.

Figure 2. Externalities of different types of capital inflows

Dollar debt, for example, imposed a long-run average externality of 1.54% annually on the Indonesian economy over the past two decades. However, during the East Asian crisis of 1997/98, the externality reached 30.70%, justifying a tax of equal magnitude on the eve of the crisis.

More generally, optimal policy measures on capital inflows should be regularly adjusted for changes in the financial vulnerability of the economy (see Jeanne and Korinek 2010). The externalities of foreign capital rise during booms when leverage increases and financial imbalances build up. After a crisis has occurred and economies have de-levered, new capital inflows create smaller externalities, justifying a zero tax in bad times when a country seeks to attract more capital. Optimal capital flow regulation should therefore be strongly procyclical. For dollar debt, a tax of between 0 and 30%, with an average of 1.5%, can be justified for the case of Indonesia.

The maturity structure of debt flows also plays a crucial role. International creditors often refuse to roll over short-term debt when financial conditions in an emerging economy deteriorate, creating a large risk of instability. On the other hand, long-term loans cannot be recalled before their maturity date.

Design and implementation issues

While the theoretical case for capital controls is compelling, the practical implementation poses a number of challenges in today’s globalised financial markets where multinational companies and armies of traders seek to arbitrage around any hurdle that policymakers throw in the way of free capital flows. An essential aspect in designing capital controls is therefore to think about how to minimise possibilities for evasion or corruption.

Nonetheless, the threat of circumvention is no excuse for inaction. Policymakers who refrain from intervention in the face of inflows that create substantial vulnerabilities are shirking their job. Below we discuss a number of practical aspects of an optimal framework of capital flow regulation:

- The level of complexity of capital controls has to be weighed against the administrative capacity of regulators. In less developed economies, it may be preferable to impose uniform controls on all capital inflows, set at a level that reflects the risk of foreign currency denominated debts. In economies with a higher level of institutional development, more complex controls that distinguish between different forms and maturities of capital flows are strongly desirable. If capital flow regulation taxes risky forms of flows more than safe forms, then it will achieve a shift in the liability structure of emerging economies towards safer forms of finance. This composition effect would make the economy more robust to shocks.

- Tax-like measures are likely to be more effective than unremunerated reserve requirements in the current economic environment. Both forms of capital controls have been used in practice, and economic theory suggests that the two measures are largely equivalent since the opportunity cost of not receiving interest on reserves amounts to a tax. However, at present, the cost of holding reserves is extremely low since global interest rates are close to zero and global liquidity is ample. This implies that reserve requirements would have to be set to substantial levels to actually affect investor behaviour and that the opportunity cost of such reserves fluctuates wildly with small changes in interest rates.

- Controls on the stock of foreign capital in the country are more desirable than controls that are solely based on inflows, since potential capital flow reversals depend on the stock of foreign capital in the country. This can be implemented e.g. by requiring foreigners to hold their investments in designated “non-resident investment accounts” and by accruing regulatory taxes on these accounts on a daily basis. Solely taxing inflows runs the risk of increasing volatility by creating incentives for global investors to increase capital inflows right before capital controls are tightened.

- Controls should adapt to macroeconomic circumstances. The vulnerability of emerging economies – and therefore the externalities created by capital inflows – fluctuates with the domestic business cycle in emerging economies as well as with global liquidity conditions (see e.g. Korinek 2010a). Just as central bankers adjust interest rates in response to inflationary pressure, regulators in emerging markets have to regularly adjust their policy measures to reflect the given macroeconomic environment.

References

Ostry, Jonathan D, Atish R Ghosh, Karl Habermeier, Marcos Chamon, Mahvash S Qureshi, and Dennis BS Reinhardt (2010), “Capital Inflows: The Role of Controls, International Monetary Fund”, Staff Position Note 10/04.

Jeanne, Olivier and Anton Korinek (2010), “Managing Credit Booms and Busts: A Pigouvian Taxation Perspective”, CEPR Discussion Paper 8015.

Korinek, Anton (2010a), “Hot Money and Serial Financial Crises”, University of Maryland, working paper.

Korinek, Anton (2010b), “Regulating Capital Flows to Emerging Markets: An Externality View”, University of Maryland, working paper.

Mendoza, Enrique G. (2006), “Lessons from the Debt Deflation Theory of Sudden Stops”, American Economic Review Papers & Proceedings, 96(2):411-416.

Reinhart, Carmen M. and Vincent Reinhart (2008), “Capital Flow Bonanzas: An Encompassing View of the Past and Present”, CEPR Discussion Paper 6996.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2002), Globalization and its Discontents, WW Norton, New York and London.