Statistical offices of many countries measure the costs of home ownership by computing imputed rents, which are then included in headline inflation measures. This is the case for the US, Japan, and Switzerland, among others. In contrast, the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) – the EU’s most important inflation statistic – excludes owner-occupied housing, for the technical reason that imputed transactions are inconsistent with the definition of the HICP, and a more complex approach based on net acquisitions would be required (Eurostat 2012, 2013).

Eurostat has been considering adding the cost of owner-occupied housing to the HICP for many years. It does not, partly because the net acquisitions approach implies that house prices are directly included in the HICP (alongside property charges, and costs of repairs and maintenance). Because house purchases involve a substantial investment component, their inclusion in headline inflation makes many statisticians uneasy. Conceptually, however, homes are a special case of durable goods, because they provide a claim on a stream of future services. Cecchetti (2007), for example, showed the long-term capital gain from home ownership is very small.

Macroprudential reasons for including house prices

House prices, of course, are important for financial stability in their own right, and in our recent work we argue that including them in official inflation measures can help integrate monetary and macroprudential policies (Hampl and Havranek (2017). Many economists have constructed early warning systems for financial crises in which house prices play a prominent role (e.g. Reimers 2012, Babecky et al. 2013, Antunes et al. 2014, Laina et al. 2015, Tölö 2015). The prominence of house prices in early warning indicators leads some to stress the interaction between their value and the monetary policy stance. As with many other issues in the recent discussion on macroprudential policy, however, there is no clear consensus.

One stream of thought, represented by Assenmacher-Wesche and Gerlach (2010) and Svensson (2014) among others, asserted that it is too costly and detrimental to the welfare of the country to use monetary policy to slow an increase in house prices. Williams (2015) conducted a meta-analysis of the empirical estimates reported in this body of research and found that typically, a 4% reduction in house prices delivered by monetary policy contraction is associated with a 1% loss of GDP.

But this discussion often omits the positive effects of this policy on GDP and employment during the downturn, when traditional CPI targeting, taking house prices into account, implies less easing than what would otherwise be optimal. In other words, it is important to highlight that inflation targeting is symmetrical, whatever the composition of the inflation series.

Several studies have demonstrated the usefulness of incorporating financial stability considerations (including, most prominently, house prices) into monetary policy rules under inflation targeting. For example, Aydin and Volkan (2011) provided evidence for this. They used a structural model of monetary policy calibrated for South Korea, and found that paying attention to house prices creates smoother business cycle fluctuations than conventional inflation targeting.

Conceptual reasons for including house prices

House prices are typically excluded from official inflation measures, although other goods that also provide a flow of future services (durables such as motor vehicles and washing machines) are included. There is no clear theoretical reason beyond intuition and convenience for this convention. The argument in favour is that for houses, the investment component relative to the consumption component is larger than for durables such as cars. Also, a portion of the value, such as land, does not depreciate, and is therefore often considered a good store of value.

Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that many households treat at least their first home purchase more as consumption than investment. And theoretically, the prices of all assets, including houses, stocks, and bonds, should in principle be included in inflation if we are to measure the current cost of expected lifetime consumption, instead of merely current consumption (Alchian and Klein 1973).

Aside from the well-known studies by Alchian and Klein (1973) and Goodhart (2001), many other authors have argued for the inclusion of house prices in the consumer price index. For example, Bryan et al. (2002) showed that, in the US, the omission of house prices introduces an excluded goods bias, and results in underestimation of CPI by about 0.25 percentage points annually. Diewert and Nakamura (2009) also pointed to the need for a more direct measure of house price inflation in the official CPI index. They suggested that the recent period of low official inflation may be a mismeasurement of underlying consumer prices.

Practical consequences of a change in the HICP

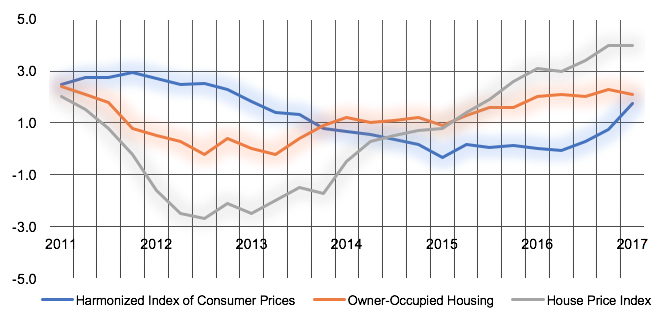

Figure 1 shows Eurozone quarterly year-on-year changes in the HICP, an index of owner-occupied housing consistent with the HICP, and a pure house price index. The growth in the latter two indices was below official inflation between 2011 and 2014, and has exceeded official inflation since 2015. It follows that including the cost of home ownership in the HICP would make the monetary policy of the ECB, if anything, more countercyclical. The extent of this effect depends on the weight attributed to the owner-occupied housing index or the house price index, but even a weight of 10% would mean a difference in the HICP of up to half a percentage point in some periods.

Figure 1 Giving non-zero weight to house prices would make monetary policy in the Eurozone more countercyclical

Notes: Aggregate index of owner-occupied housing for the Eurozone computed using the weights for each country in Eurostat’s construction of the harmonized index of consumer prices.

Source: Eurostat.

The delay in data availability is a frequent argument against the inclusion of house prices. This is a problem, but one that has been overcome by several statistical offices (Hampl and Havranek 2017). For example, Czech headline monthly inflation includes house prices with a 1.4% weight for most regions, and with a 2.3% weight for Prague, the capital city. The Czech National Bank, unusually for a central bank, computes its own supplementary inflation index (the CPIH) in which house prices get a 15% weight, based on the share in consumers’ expenditure. The Bank makes this index available in its inflation report. In some countries, it is possible to take the data directly from the land registry, where all price information is available within a few days after property changes hands.

The core is rotten

Among the many arguments for including the costs of home ownership in headline CPI, a prominent one is that it would bring the CPI index closer to what most people consider inflation to be. In a well-known, colourfully titled paper, “Measuring inflation: the core is rotten", James Bullard, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, criticised the Federal Reserve’s focus on core inflation and argued that we should pay more attention to a broader gauge. To paraphrase Bullard’s (2011) provocative statement: an immediate benefit of moving away from the sole emphasis on an inflation measure that excludes the costs of home ownership would be to reconnect central banks and statistical bureaus with households and businesses who know price changes when they see them.

References

Alchian, A and B Klein (1973), “On a correct measure of inflation”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 5(1): 173–91.

Antunes, A, D Bonfim, N Monteiro, and P Rodrigues (2014), “Early warning indicators of banking crises: exploring new data and tools”, Economic Bulletin and Financial Stability Report Articles, Bank of Portugal.

Assenmacher-Wesche, K and S Gerlach (2010), “Monetary policy and financial imbalances: facts and fiction”, Economic Policy 25: 437–82.

Aydin, B and E Volkan (2011), “Incorporating financial stability in inflation targeting frameworks”, IMF Working Papers, no 11/224.

Babecky, J, T Havranek, J Mateju, M Rusnak, K Smidkova, and B Vasicek (2013), “Leading indicators of crisis incidence: evidence from developed countries”, Journal of International Money and Finance 35(C): 1–19.

Bryan, M, S Cecchetti, and R O’Sullivan (2002), “Asset prices in the measurement of inflation”, NBER Working Papers, no 8700.

Bullard, J (2011), “Measuring inflation: the core is rotten”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review July: 223–34.

Cecchetti, S (2007), “Housing in inflation measurement”, VoxEU, 13 June.

Diewert, W and A Nakamura (2009), “Accounting for housing in a CPI”, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia working paper no 09-4.

Eurostat (2012), Detailed technical manual on owner-occupied housing for harmonized index of consumer prices, technical report, March.

Eurostat (2013), Methodological manual referred to in Commission Regulation (EU) No 93/2013, technical report, February.

Goodhart, C (2001), “What weight should be given to asset prices in the measurement of inflation?”, Economic Journal 111(472): F335–56.

Hampl, M and T Havranek (2017), “Should monetary policy pay attention to house prices? The Czech National Bank’s approach”, BIS Papers (forthcoming).

Laina, P, J Nyholm, and P Sarlin (2015), “Leading indicators of systemic banking crises: Finland in a panel of EU countries”, European Central Bank working paper, Series 1758.

Reimers, H (2012), “Early warning indicator model of financial developments using an ordered logit”, Business and Economic Research 2(2): 171–91.

Svensson, L (2014), “Inflation targeting and leaning against the wind”, International Journal of Central Banking 10(2): 103–14.

Tölö, E (2015), “Early warning indicators of banking crises”, Bank of Finland Bulletin, no 2/2015.

Williams, J (2015), “Measuring monetary policy’s effect on house prices”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, FRBSF Economic Letter, no 2015-28.