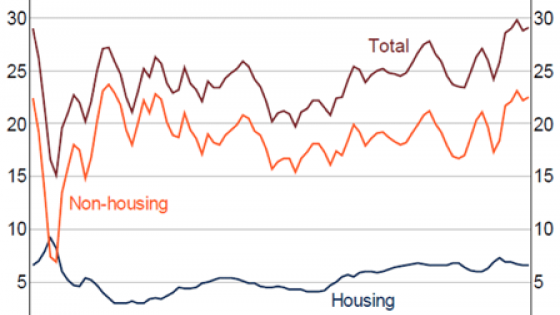

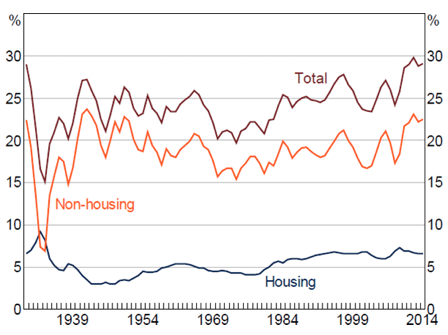

A key observation in Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Piketty 2014) is that the share of aggregate income accruing to capital in the US has been rising steadily in recent decades (Figure 1). The growing disparity between the income going to wage earners and capital owners has led to calls for government intervention. But for such interventions to be effective, it is important to ask who the capital owners are.

Figure 1. Net capital income, US (share of net domestic income)

Notes: Net capital income is equal to net operating surplus, or gross operating surplus less depreciation; net domestic income is equal to gross domestic product less total depreciation

Sources: Author's calculations; Bureau of Economic Analysis; Piketty and Zucman (2014)

Recent research has shown that the long-run rise in the net capital income share is mainly due to the housing sector (e.g. Rognlie 2015, Torrini 2016 – see Figure 1). This phenomenon is not specific to the US but has been evident in almost every advanced economy. This suggests that it is not entrepreneurs and venture capitalists that are taking an increasing share of the economy, but land owners.

So are we seeing the rise of a new `landed gentry’?1 And, if we are, what might explain it? Several research papers (e.g. Bonnet et al. 2014, Rognlie 2015, Weil 2015), print articles (e.g. Economist 2015) and blogs (e.g. Smith 2015) have hypothesised that the long-run increase in the housing income share is due to factors such as lower interest rates, higher mortgage debt, and constraints on home building, due to either geographic constraints or land zoning restrictions. But there is comparatively scarce empirical evidence to confirm these hypotheses.

In a new paper, I examine the determinants of the rise in the US housing capital income share over recent decades (La Cava 2016). I build upon the foundations set by Piketty and Zucman (2014), but rather than focusing on trends at the national level, I dig deeper and decompose the US national accounts data by different types of housing (e.g. owner-occupied and tenant-occupied) and, even more importantly, by US state. To the best of my knowledge, my paper is the first to explore the determinants of the secular rise in the housing share of the economy by exploiting both cross-sectional and time-series variation in factors such as housing prices, interest rates and housing supply constraints.

In the US national accounts, income accruing to the housing sector is measured as ‘net housing capital income’, or simply, net rental income (i.e. gross rents less housing costs, such as depreciation and property taxes). This measure includes rental income going to both owner-occupiers (imputed rent) and landlords (market rent).2 The very detailed nature of the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ regional economic accounts allows for similar estimates of housing capital income to be constructed for each US state spanning several decades.

This investigation reveals three things about the rise in the US housing capital income share in recent decades. First, it has occurred due to an increasing share of income accruing to owner-occupiers through imputed rent. Second, it is concentrated in states that are constrained in terms of new housing supply. Finally, it is closely associated with the long-run decline in real interest rates and inflation.

My results suggest that the ‘rise of housing’ is intimately linked to the same factors that underpin ‘secular stagnation’ (Summers 2014) – that is, the gradual decline in real (and nominal) interest rates since the 1980s has contributed to a gradual run-up in housing prices, and led to household wealth and income being increasingly concentrated in the hands of landowners. This in turn may have implications for intergenerational inequality, given that the home is a key mechanism through which wealth and income are transferred across generations.

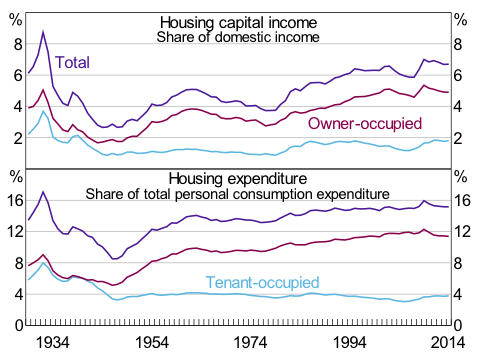

Result 1: It’s (mainly) an owner-occupier story

The decomposition of the national accounts by type of housing indicates that the secular rise is mainly due to a rising share of imputed rent going to owner-occupiers. The owner-occupier share of aggregate income has risen from just under 2% in 1950 to close to 5% in 2014 (top panel of Figure 2). The share of income going to landlords (i.e. market rent) has also doubled in the post-war era. But, in aggregate, the effect of imputed rent is larger simply because there are nearly twice as many home owners as renters in the US economy. A similar phenomenon is observed in the personal consumption expenditure data (bottom panel of Figure 2). In other words, today’s landed gentry are predominantly home owners, not private landlords.

Figure 2. Housing capital income and expenditure

Note: Housing capital income measured as the net operating surplus of the housing sector

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

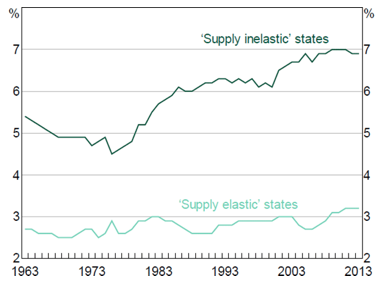

Result 2: Housing supply constraints matter

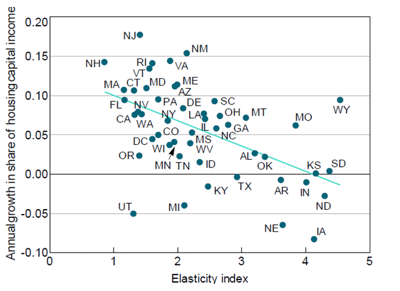

The geographic decomposition reveals that the long-run rise in the housing capital income share is fully concentrated in states that face housing supply constraints. To see this, I divide the states into ‘elastic’ and ‘inelastic’ groups based on whether the state is above or below the median housing supply elasticity index (as measured by Saiz 2010). This index captures both geographical and regulatory constraints on home building across different US regions. For 50 years, the share of total housing capital income going to the supply-elastic states has been unchanged at about 3% of GDP (Figure 3). In contrast, the share going to the supply-inelastic states has risen from around 5% in the 1960s to 7% of GDP more recently. Notably, these divergent trends in housing capital income are not due to a few ‘outlier’ states where housing supply is particularly constrained, such as New York or California – instead, there is a clear negative correlation between the long-run growth in housing capital income and the extent to which housing supply is constrained across all states (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Contributions to gross housing capital income (as a share of total GDP)

Notes: Housing capital income measured as the gross operating surplus of the real estate sector; the analysis abstracts from changes in depreciation due to the data being unavailable at the level of US state

Sources: Author's calculations; Bureau of Economic Analysis; Saiz (2010)

Figure 4. Housing capital income growth and the elasticity of housing supply (1980–2014 average)

Notes: Share of housing capital income measured as housing gross operating surplus divided by GDP at state level; the estimated correlation coefficient shown is −0.52

Sources: Author's calculations; Bureau of Economic Analysis; Saiz (2010)

Result 3: Interest rates (and inflation) matter

Finally, I provide statistical evidence that the rise in the share of housing capital income in recent decades is correlated with declines in both real interest rates and inflation, with these effects being particularly strong in supply-constrained states.

In a state-level panel regression framework, there is a strong negative correlation between the housing capital income share and nominal interest rates. Moreover, a simple decomposition using the Fisher equation reveals that the rise in housing capital income across states and over time is associated with declines in both real interest rates and consumer price inflation.

The results are consistent with the argument that consumer price disinflation and the deregulation of the US mortgage market during the 1980s and 1990s acted as positive credit supply shocks (with high inflation and credit market regulation in the 1970s acting as artificial borrowing constraints). The associated decline in nominal interest rates lowered the cost of owning a home and increased the demand for housing for credit-constrained households (Ellis 2005). The resulting increase in housing demand led to higher relative prices for land in areas that were constrained in terms of new housing supply. This rise in the relative price of land, in turn, led to an increase in the share of nominal spending on housing.3 Sommer et al. (2013) and Stiglitz (2015) outline theories that are consistent with this story.

The results are robust to different measures of housing capital income, to controls for observable state-level characteristics (e.g. population and income growth), and to unobservable state factors that do not vary with time (e.g. local amenities and distance to the coast).

Implications and directions for future research

My research highlights the important role of housing in not only the distribution of wealth, but also the distribution of income in the US. Indeed, the observed increase in the share of aggregate income going to housing capital might even understate the importance of housing prices for the income distribution. The non-housing capital income share has been stable for several decades (as shown in Figure 1), but within the non-housing sector, there has been an increase in the share of capital income going to financial corporations. Much of the income flowing to the financial sector is likely related to the growth in intermediation services – services that are traditionally dependent on housing collateral and, ultimately, land prices.

My results also potentially speak to a new literature on the distributional effects of monetary policy. This literature is still in its infancy, but it is surprising how little research there has been on the link between monetary policy and inequality via the housing sector. As is well-known, for most advanced economies housing assets typically comprise the largest share of total wealth for most households. Moreover, imputed rent for owner-occupiers often makes up the largest share of total household spending in the national accounts. The link between monetary policy and inequality via housing prices and imputed rent should therefore be a fruitful area of future research.

Authors’s note: The author completed this project while visiting the Bank for International Settlements under the Central Bank Research Fellowship program. The views expressed in this column and the associated paper are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reserve Bank of Australia or the Bank for International Settlements. The author is solely responsible for any errors.

References

Albouy, D, G Ehrlich, and Y Liu (2014), “Housing Demand and Expenditures: How Rising Rent Levels Affect Behavior and Cost-Of-Living over Space and Time”, Paper presented at CEP/LSE Labour Seminar, London, 28 November.

Bonnet, O, P-H Bono, G Chapelle, and E Wasmer (2014), “Does Housing Capital Contribute to Inequality? A Comment on Thomas Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century”, Sciences Po Economics Discussion Paper No 2014-07.

Economist, (2015), ‘The Paradox of Soil’, 4 April, 18–20.

Ellis, L (2005), “Disinflation and the Dynamics of Mortgage Debt”, Investigating the Relationship between the Financial and Real Economy, BIS Papers No 22, Bank for International Settlements, 5–20.

La Cava, G (2016), `Housing Prices, Mortgage Interest Rates and the Rising Share of Capital Income in the United States’, Reserve Bank of Australia Research Discussion Paper, No 2016-04. Also published as BIS Working Papers No 572, Bank for International Settlements.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. A Goldhammer, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Piketty, T, and G Zucman (2014), “Capital is Back: Wealth-Income Ratios in Rich Countries 1700–2010”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129 (3), 1255–1310.

Rognlie, M (2015), “Deciphering the Fall and Rise in the Net Capital Share: Accumulation or Scarcity?”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 1–54.

Saiz, A (2010), “The Geographic Determinants of Housing Supply”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125 (3), 1253–1296.

Smith, N (2015), “The Threat Coming by Land”, Bloomberg View, 9 September.

Sommer, K, P Sullivan, and R Verbrugge (2013), “The Equilibrium Effect of Fundamentals on House Prices and Rents”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 60 (7), 854–870.

Stiglitz, J E (2015), “New Theoretical Perspectives on the Distribution of Income and Wealth among Individuals: Part IV: Land and Credit”, NBER Working Paper No 21192.

Summers, L H (2014), “Reflections on the New ‘Secular Stagnation Hypothesis’”, VoxeEU.org, October 30 2014.

Torrini, R (2016), “Labour, Profit and Housing Rent Shares in Italian GDP: Long-Run Trends and Recent Patterns”, Banca D’Italia Questioni di Economia e Finanza, No 318.

Weil, D N (2015), “Capital and Wealth in the Twenty-First Century”, The American Economic Review, 105 (5), 34–37.

Endnotes

[1] The landed gentry was an historical British social class consisting of land owners who lived mainly off rental income.

[2] The long-run rise in the `housing capital share’ of the US economy is not specific to the national accounts, but can also be observed across a range of US household surveys (Albouy, et al. 2014).

[3] Structural factors such as an increase in the home ownership rate and an increase in the average size and quality of housing are important in explaining the increase in the housing capital income share in the period immediately after the Second World War. However, these structural factors appear to have been less important in explaining the ‘rise of housing’ in the period since the early 1980s.