With the new Republican majority in both Houses of the US Congress, the Fed Oversight Reform and Modernization (FORM) Act that was passed by the House of Representatives in November 2015 is receiving renewed attention. Section 2 requires that the Fed:

- “describe the strategy or rule of the Federal Open Market Committee for the systematic quantitative adjustment” of its policy instruments; and

- compare its strategy or rule with a reference rule.1

Janet Yellen, Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, is to be complimented for using such comparisons with reference rules in her communication about Fed policy. Just recently, in a speech at Stanford on 19 January, she discussed how current Fed policy compares to several simple policy rules.2

For example, Yellen uses the well-known Taylor rule as a reference point. Additionally, she considers two other rules, which she calls the ‘balanced-approach rule’ and the ‘change rule’. Looking forward, she contrasts the implications of the rules with the FOMC members’ projections for the federal funds rate. She states that such benchmark rules “can be helpful in providing broad guidance about how the federal funds rate should be adjusted over time in response to movements in real activity and inflation.” Yet, as Yellen notes, “the Taylor rule prescribes a much higher path for the federal funds rate than the median of (FOMC) participants’ assessments of appropriate policy”.

Yellen goes on to make the important argument that “if the neutral rate were to remain quite low over the medium term, .., then the appropriate setting for R-Star in the Taylor rule would arguably be zero, yielding a yet lower path for the federal funds rate.” To support her argument, she refers to estimates of this R-Star by Holston et al. (2017).

However, as we show below, if one uses an estimate of potential real activity that is consistent with this R-Star estimate, the argument is turned on its head. Since the consistent estimate of potential real activity is lower than the one considered by Yellen, it implies federal funds rate prescriptions that have been above Fed policy for quite some time. Thus, a consistent use of these estimates indicates that Fed policy has been rather loose relative to such a reference rule.

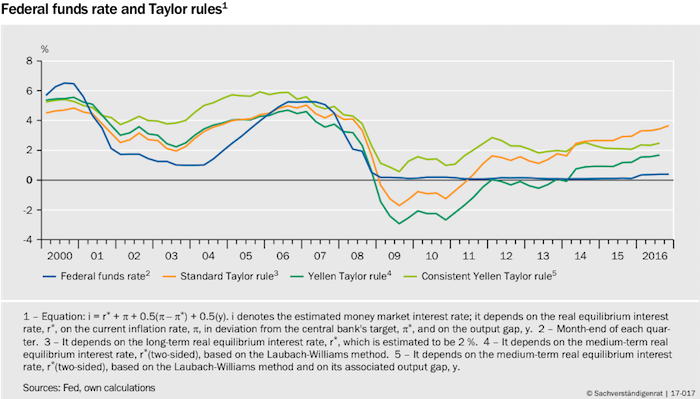

This is shown in Figure 1. The blue line is the actual federal funds rate. The orange line indicates the prescriptions from the (standard) Taylor rule. The dark green line (labelled the “Yellen Taylor Rule”) uses the lower neutral rate/R-Star estimate suggested by Yellen (2016). Its prescriptions for the funds rate are quite a bit lower. However, once the consistent estimate of potential real activity is used along with the R-Star estimate, the interest rate prescriptions move back up as shown by the light-green line in Figure 1 (labelled the “consistent Yellen Taylor rule”).

Figure 1 Federal funds rate and Taylor rules

R-Star and other ingredients in the reference rules

Let’s take a closer look why this is so. The Taylor rule prescribes a value for the federal funds rate that deviates from its long-run equilibrium whenever inflation deviates from a target of 2% and output deviates from potential (Taylor 1993). Here’s the formula:

Fed Funds Rate = R-Star + Target + 1.5 (Inflation – Target) + 0.5 (Output Gap)

The equilibrium funds rate is simply the sum of the long-term equilibrium real rate, the ‘infamous’ R-Star, and the target rate for inflation. Taylor (1993) puts both at 2%. For inflation, the 2% value actually coincides with the Fed’s longer-run goal made public in 2012 and measured with the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) Index. For R-Star, Taylor (1993) used trend GDP growth, which stood at 2.2% between 1984 and 1992. Incidentally, the same estimate of R-Star stands even a bit higher between 1984 and 2016.

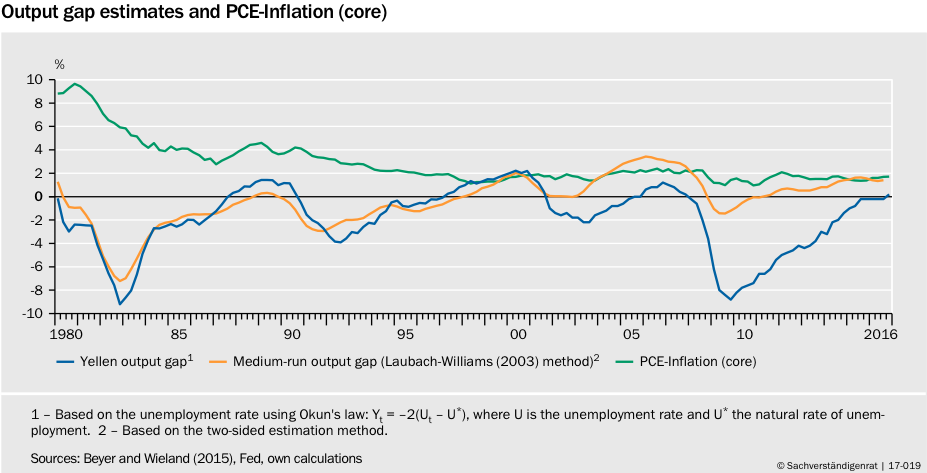

The standard Taylor rule shown in Figure 1 uses a 2% R-Star, core PCE inflation (green line in Figure 2), and the output gap proposed by Yellen (2016). This output gap (blue line in Figure 2) is based on the unemployment rate using Okun’s law with an estimate of the long-run NAIRU. This output gap measure declines following the outbreak of the financial crisis reaching a trough of -8% in 2010, and it has just been closed in 2016.

Figure 2 Output gap estimates and PCE-inflation (core)

Medium-run equilibrium rates

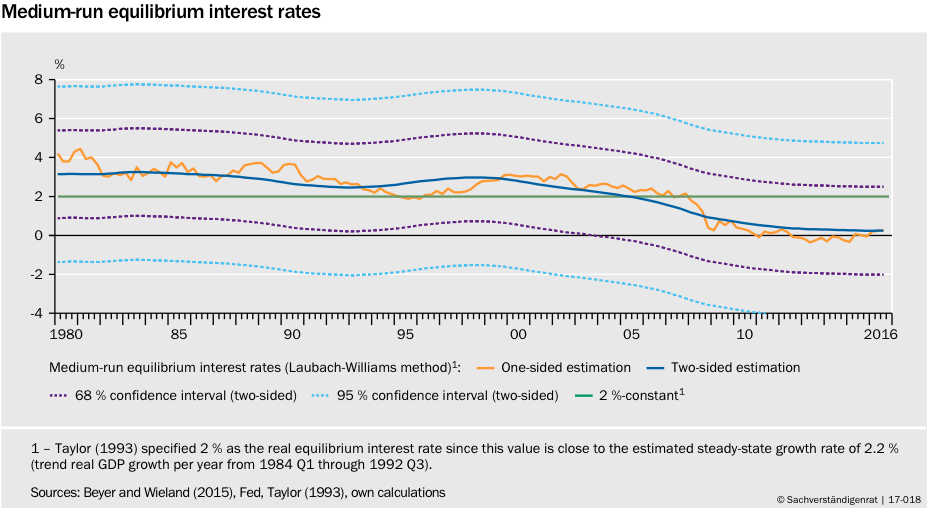

The Yellen Taylor rule instead uses estimates of the equilibrium real rate based on a methodology as appears in Laubach and Williams (2003) and Holston et al. (2017). (For the calculation, see Beyer and Wieland 2014 and GCEE 2015, 2016.) This is best characterised as a medium-run equilibrium rate. It is estimated within a three-equation model consisting of an aggregate demand curve, an inflation Phillips curve, and a definition linking potential growth and the equilibrium interest rate/R-Star. This setup contains a number of temporary and permament shocks. The estimate of the medium-run equilibrium rate can change substantially within short periods of time. As shown by the orange line in Figure 3, it declined sharply with the recession in 2008/2009 and has hovered near zero since then.

Figure 3 Medium run equilibrium interest rates

Using the estimate of the medium-run equilibrium rate in place of the long-run equilibrium R-Star, the Yellen Taylor rule (green line in Figure 1) results in much lower federal funds rate prescriptions than the standard Taylor rule.

However, the estimates of potential real activity and the output gap obtained with the methodology as in Laubach and Williams (2003) are quite different from those in the Yellen Taylor rule, which are derived from a long-run NAIRU. The medium-run output gap (orange line in Figure 2) declines much less in the 2008/09 recession. The trough occurs at about -2%. The output gap estimate is back in positive territory by 2011. A deeper trough and longer-lasting negative output gap would have implied substantial deflation according to the estimated Phillips curve. Absent deflation, potential is revised down and the output gap is revised upwards. Along with the lower potential and trend growth, the equilibrium rate estimate declines. Consequently, using the consistent medium run estimates of R-Star and the output gap, the federal funds rate prescriptions from the consistent Yellen Taylor rule turns out to be quite a bit higher than when the long-run NAIRU-based output gap is used.

The balanced-approach rule, also considered by Yellen, doubles the coefficient on the output gap to unity. Thus, the interest rate prescriptions from the balanced-approach rule would be even higher. Finally, the change rule uses first-differences, thereby removing R-Star considerations from the formula.

R-Star, reference rules, and Fed independence

In conclusion, with the use of simple reference rules one can illustrate quite clearly the impact of changes in R-Star and potential real activity on the path for monetary policy. In this sense, the comparative approach that would be required under Section 2 of the FORM Act proves quite useful. It also helps pointing out that insisting on consistency in the gap and equilibrium measures has important implications for how to interpret current policy. Specifically, the decline in R-Star estimates does not justify the current policy stance. Rather, consistent application suggests that policy should be tightened. Whether these medium-run estimates, following Laubach and Williams (2003), should really be given so much attention is another question. For one thing, they are extremely imprecise as indicated by the wide confidence bands in Figure 3. They are very sensitive to technical assumptions (Beyer and Wieland 2015, GCEE 2015), as Laubach and Williams (2003) have stressed. Others have pointed to a number of reasons why these estimates may suffer from omitted variable bias (Taylor and Wieland 2016, Cukierman 2016). Thus, it would be better not to use them as key determinant of the policy stance.

Importantly, however, these comparisons of Fed policy to simple reference rules show how such legislation would serve to bolster the Federal Reserve’s independence. Just imagine, if ever a president would try to exert pressure on the Fed to keep interest rates too low for too long in order to boost activity during his or her term and improve chances of reelection. This has a name – it’s a political business cycle. Clearly, by referring to such legislation and appropriate reference rules, the Fed would be able to better stand up to such pressure and more effectively communicate its reasons to the public.

References

Beyer, R C M and V Wieland (2015) “Schätzung des mittelfristigen Gleichgewichtszinses in den Vereinigten Staaten, Deutschland und dem Euro-Raum mit der Laubach-Williams-Methode”, GCEE Working Paper 03/2015, Wiesbaden, November.

Cukierman, A (2016) “Reflections on the natural rate of interest, its measurement, monetary policy and the zero bound”, CEPR Discussion paper 11467.

GCEE (2016) “Time for reforms”. Annual economic report, German Council of Economic Experts, 2 November.

GCEE (2015), “Focus on future viability”, Annual economic report, German Council of Economic Experts, 11 November.

Laubach, T and J C Williams (2003) “Measuring the natural rate of interest”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4): 1063-1070.

Holston, K, T Laubach and J C Williams (2017) “Measuring the natural rate of interest: International trends and determinants”, Journal of International Economics, in press.

Taylor, J B and V Wieland (2016) “Finding the equilibrium real interest rate in a fog of policy deviations”, Business Economics, 51(3): 147-154.

Yellen, J (2016) “The economic outlook and the conduct of monetary policy”, Remarks at Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, Stanford University, 19 January.

Yellen, J (2015) “Normalizing monetary policy: Prospects and perspectives”, Remarks at the conference on New Normal Monetary Policy, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Endnotes

[1] For more information on the legislation and why the Requirements for Policy Rules of the Federal Open Market Committee are supported by leading scholars of monetary economics see here.

[2] This can be found in the third section of the speech under the heading “Evaluating the appropriate stance of monetary policy” (Yellen 2016).