The massive fall in economic activity caused by COVID-19 and the widespread business support implemented by governments may have affected employment dynamics and reallocation, with potentially important consequences for aggregate productivity.

Early studies on the topic have focused on a single country (Bahar et al. 2021, Cros et al. 2021), a small set of countries (Andrews et al. 2021, Bighelli et al. 2021) or on a small subsample of firms when covering many countries (Harasztosi and Savšek 2022). Cross-country evidence that focuses on the universe of firms, allowing to highlight trends that are common across countries while disentangling country-specific dynamics in each setting, is key to informing policy design and action going forward.

In a recent paper (Calligaris et al. 2023), we fill precisely this gap by investigating (i) employment dynamics across firms along the intensive and extensive margins during the COVID-19 pandemic, (ii) the extent to which these adjustments were productivity enhancing, and (iii) the role of job retention schemes in shaping these patterns.

Our analysis relies on a combination of novel and unique data. First, in collaboration with 12 participating countries, we collected high-frequency harmonised micro-aggregated statistics, computed using administrative data on employment and wages from electronic payroll records linked to monthly information on policy support during COVID-19.

The data cover almost the universe of firms and/or worker-firm relationships in the non-financial business sector. Second, we built a new cross-country and high-frequency (monthly) de jure indicator of job retention schemes, allowing researchers to benchmark such schemes across countries and over time.

How did employment adjust during the crisis?

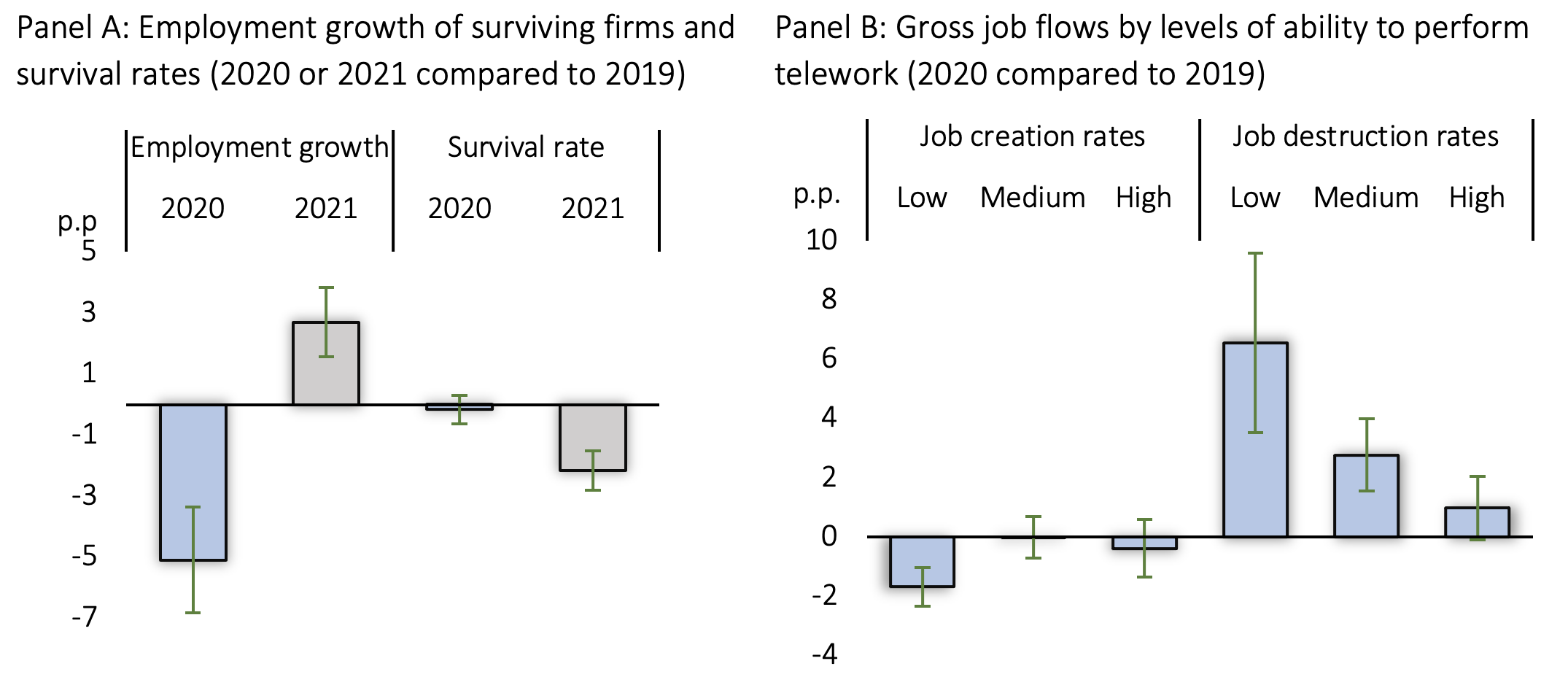

Following the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, employment adjusted through different margins and the contribution of each margin changed over time (Figure 1, Panel A). In 2020, employment adjusted mainly along the intensive margin, with a decline in employment growth of surviving firms relative to 2019, while survival rates remained on average stable. In 2021, employment growth of surviving firms started to pick up, while – at the extensive margin – average survival rates started to decline (Figure 1, Panel A). These aggregated results mask cross-country and cross-sector heterogeneity, with increases (decreases) in job destruction (creation) rates that were significantly higher in low-telework sectors (Figure 1, Panel B).

Figure 1 Employment adjustment margins varied over time and across sectors

Note: Panel A presents differential employment growth rates and survival rate for 2020 and 2021 relative to the baseline rates of 2019. The estimates come from regressing employment growth and survival rates (between January of each year and January of the year after) on a dummy for the year 2020 or 2021 along with country-sector fixed effects, and weighting the regression by average sectoral employment shares (or sectoral shares in terms of number of units for survival rates). The columns represent estimated coefficients and the green bars, 95% confidence intervals. Panel B shows components of employment growth differences (gross job creation and gross job destruction rates), estimated as in Panel A, for sectors of different abilities to telework (‘low’, ‘medium’, ‘high’), between 2020 and 2019. The columns represent estimated coefficients and the green bars, 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Calligaris et al. (2023).

Was reallocation (still) productivity enhancing?

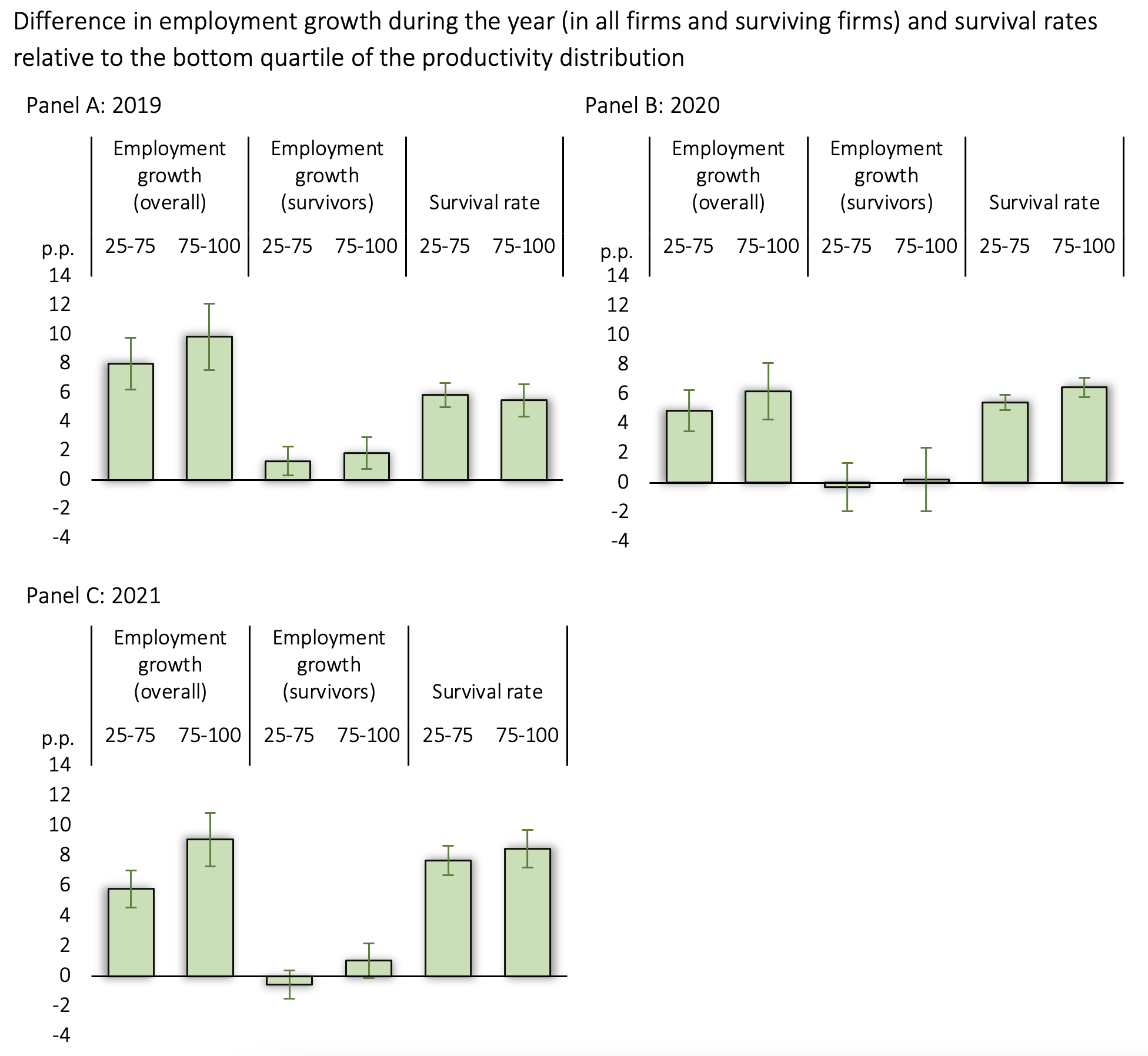

The employment effects of the COVID-19 crisis entailed a reallocation of resources across firms, which is an important factor affecting sectoral and aggregate productivity growth. Labour reallocation was productivity enhancing during the immediate pre-crisis period, as during 2019 employment growth was significantly larger for firms in the middle and top quartile of the productivity distribution relative to the least productive firms (Figure 2, Panel A). Both the extensive and the intensive margins contributed to this productivity-enhancing reallocation, with a particularly large contribution of the extensive margin.

Relative to 2019, the productivity-enhancing nature of reallocation was weaker in 2020 and 2021. More specifically, labour reallocation remained productivity enhancing both during 2020 and 2021, but to a lower extent and almost solely due to the extensive margin (Figure 2, Panels B, and C). Indeed, in both years, firm survival remained higher for firms in the middle and top of the distribution relative to firms at the bottom, while the employment growth of middle- and high-productivity surviving firms was not statistically different from that of their low-productivity counterparts. Among the countries in the sample, these patterns were more pronounced in Latvia, New Zealand, and the UK, and no country displayed a significant increase in productivity via reallocation.

Figure 2 Reallocation remained productivity enhancing, though to a lower extent

Notes: The figure presents differential employment growth rate for mid- (25–75) and high-productivity firms (75–100) relative to the baseline group of low-productivity firms (0–25) in 2019, 2020, and 2021. The estimates come from regressing employment growth (between January of each year and January of the year after) on a dummy for each productivity quantile along with country-sector fixed effects, and weighting the regression by sectoral employment shares. The columns represent estimated coefficients and the green bars, 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Calligaris et al. (2023).

How did job retention schemes affect these dynamics?

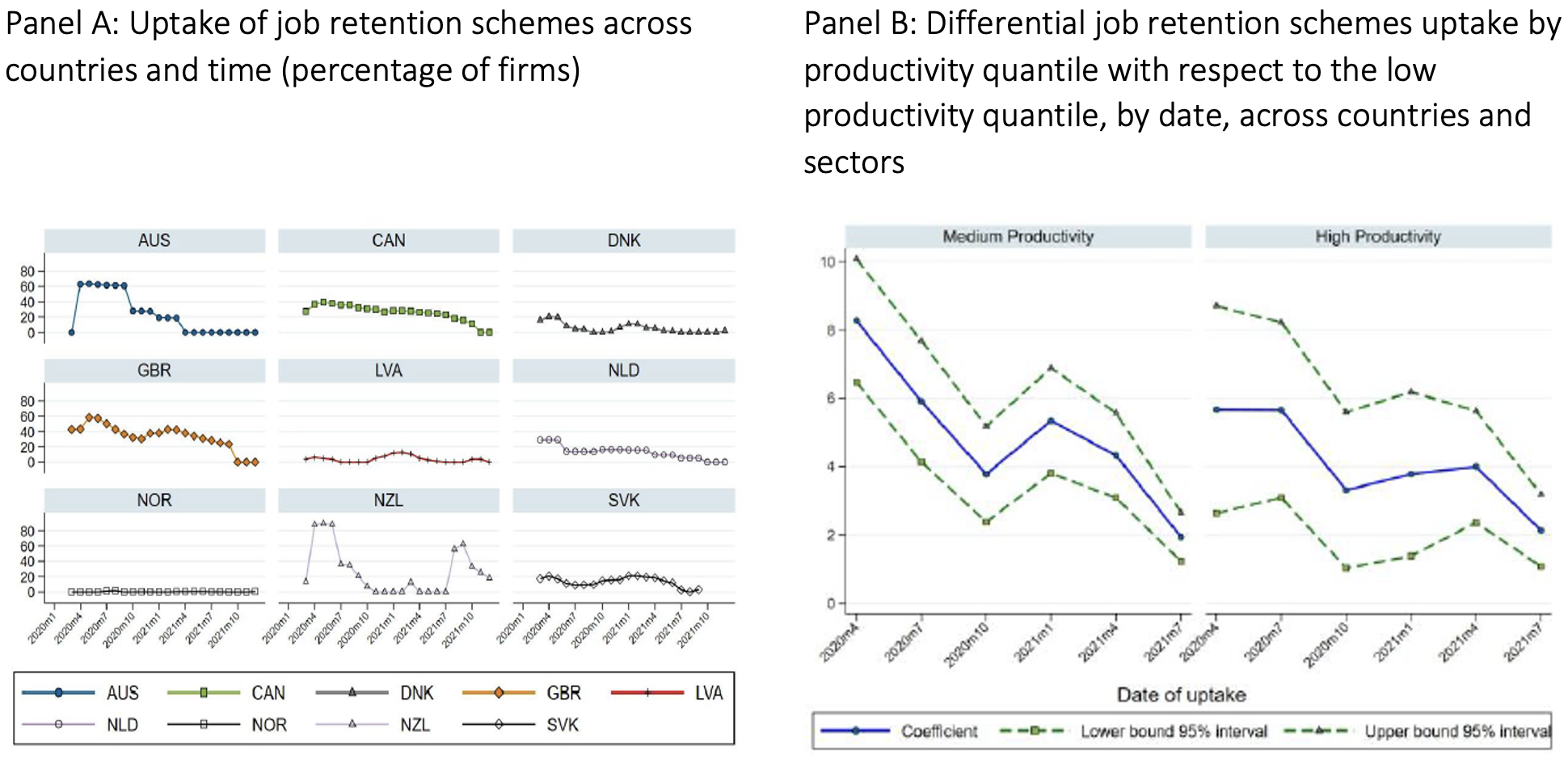

The uptake of job retention schemes by firms in the sample was on average substantial but varied markedly across countries, sectors, and over time (Figure 3, Panel A). At its highest, around 80% of firms received support in New Zealand and 60% in Australia, and more than 20% of firms were supported in European countries such as Denmark, Latvia, and the Slovak Republic. Uptake was the highest in sectors involving direct contact between customers and providers, such as the hotels and restaurants sector and was also highest on average at the time the COVID-19 pandemic hit the hardest. It was then reduced over time, and eligibility requirements to access the schemes were tightened, as countries lifted mobility restrictions.

Figure 3 Job retention schemes uptake over time, across countries and productivity quantiles

Notes: Panel A plots the percentage of firms that received support via job retention schemes (i.e. firms with at least one employee on the job retention scheme). Panel B plots the coefficient and related 95% confidence intervals of a regression of job-retention-schemes uptake on the aggregated productivity quantile (proxied by the wage quantile) categorical variable, on a cross-country sample evaluated repeatedly at different points in time, controlling for country by industry fixed effects. Each sector is weighted according to its average size in terms of employment over the year.

Source: Calligaris et al. (2023).

Interestingly, there was also heterogeneity in the allocation of support across firms within sectors. Uptake was relatively higher for firms in the middle quartiles and in the top quartile of the productivity distribution, hinting that support was not disproportionately directed towards less-productive companies (Figure 3, Panel B). The differences in uptake across productivity quantiles decreased over time, as the pandemic intensity reduced and the need for support diminished, but firms at the bottom of the productivity distribution show lower uptake of job retention schemes throughout the period in the large majority of countries.

We investigate the role of job retention schemes in shaping employment and reallocation dynamics through two complementary approaches, delivering consistent insights: (i) using firm-level information on uptake to contrast employment growth and survival rates across firms at a detailed level, and (ii) using local projections estimations exploiting ex ante differences in the generosity of support design through a novel de jure job retention schemes indicator, to further ease endogeneity concerns.

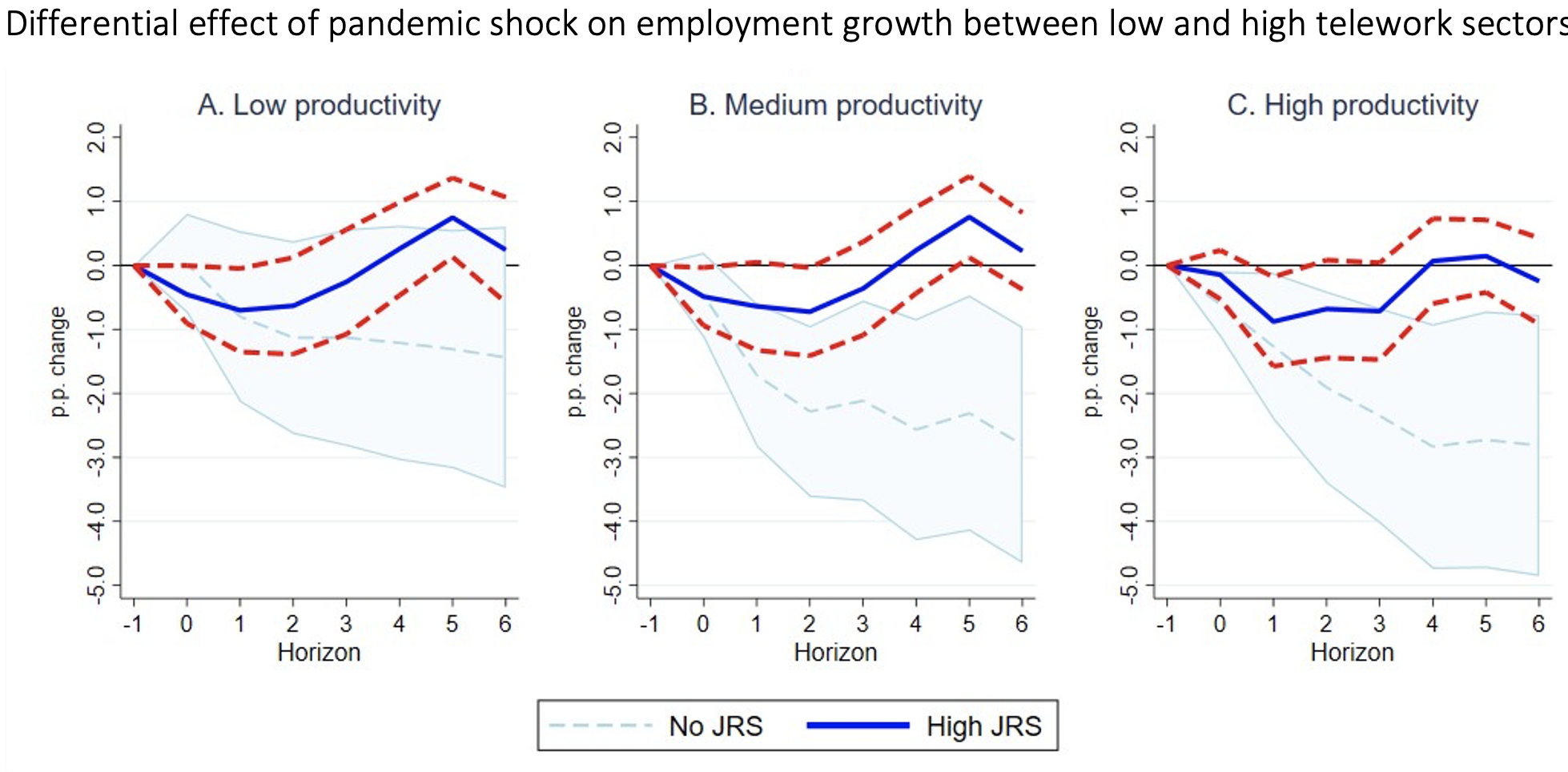

We found that job retention schemes were successful in cushioning the effect of the crisis on employment and business survival: following a tightening in the pandemic intensity, employment growth was on average lower and exit higher in the absence of job retention schemes, relative to when generous job retention schemes were in place (Figure 4). Moreover, in the absence of support, employment growth declined significantly more in both the middle- and the high-productivity quantiles relative to when more generous job retention schemes were in place, while the difference is not statistically significant when focusing on the group of low-productivity firms.

Figure 4 Job retention schemes contributed to employment preservation and did not distort productivity-enhancing reallocation

Notes: The lines represent the differential effect on employment growth for firms in more- versus less-exposed sectors of a change in the containment stringency index between 0 and 6 months after the change, if the job retention schemes indicator in the month before the change in severity was equal to 0 (no job retention schemes, light blue dotted line) or the 75th percentile (high job retention schemes, blue filled line). The red dotted lines and the solid light blue lines represent the 90% confidence interval around the estimates.

Source: Calligaris et al. (2023).

Taken together, these results suggest that government policies were effective in mitigating the effects of the crisis and did not come with distortions of the creative destruction process and of the productivity-enhancing nature of labour reallocation. Instead, not shielding the economy from the effect of the crisis could have led to a larger downsizing of mid- and high-productivity firms, with potentially relevant losses from a productivity standpoint and limited cleansing effects.

References

Andrews, D, A Charlton, and A Moore (2021), “COVID-19 and the continued labour reallocation to productive and tech-savvy firms”, VoxEU.org, 22 September.

Bighelli, T, T Lalinsky, and F di Mauro (2021), “COVID-19 government support may have not been as unproductively distributed as feared”, VoxEU.org, 19 August.

Calligaris, S, G Ciminelli, H Costa, C Criscuolo, L Demmou, I Desnoyers-James, G Franco, R Verlhac, (2023), “Employment dynamics across firms during COVID-19: The role of job retention schemes”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper 1788.

Cros, M, A Epaulard, and P Martin (2021), “Will Schumpeter catch COVID-19? Evidence from France”, VoxEU.org, 4 March.

Harasztosi, P, and S Savšek (2022), “Productivity and responses to the pandemic: Firm-level evidence”, EIB Working Papers 2022/09, European Investment Bank.