Emerging economies recurringly experience episodes of capital inflows and outflows, sudden stops, and flow reversals as they are notoriously exposed to global financial conditions. During these episodes, monetary authorities face complex trade-offs. Consider for example the effects of current US monetary tightening causing tight global financial conditions and a deterioration in economic activity in the US and globally. On the one hand, emerging economies' central banks could increase their policy rate in tandem with the Federal Reserve to avoid large fluctuations in capital flows and the exchange rates (Sunel and Mimir 2018). This choice of mimicking US monetary policy, even when inflationary pressures are not as severe at home, may indicate a lack of independent monetary policy linked to ‘fear of floating’ (Calvo and Reinhart 2002). On the other hand, central banks can lower their policy rate to alleviate the deterioration in domestic economic activity induced by contracting global demand and tighter global financial conditions.

What central banks in emerging economies do, and whether their actions are effective is ultimately an empirical question. In a recent paper (De Leo et al. 2022), we argue that the country's exposure to the global financial cycle, and whether it allows for effective monetary independence (Miranda Agrippino and Rey 2020) and the monetary policy's ability to affect local financial conditions (Kalemli Ozcan 2019) are at the centre of these issues. We show that central banks in emerging economies lower their policy rates in response to deteriorating local economic activity, yet their pass-through to short-term market rates appears compromised by their exposure to global financial conditions. Our analysis covers a large set of emerging and advanced economies at a quarterly frequency from mid-1990s to 2019.

In the column, we first document that the behaviour of central banks in emerging economies can be generally characterised by Taylor-type rules. In fact, central banks adjust the policy rate in response to changes in both inflation and economic conditions (as measured by GDP growth or the output gap). In this respect, we find that central banks in emerging economies operate similarly to central banks in advanced economies. Likewise, we find that policy rates are lower when local economic activity decelerates.

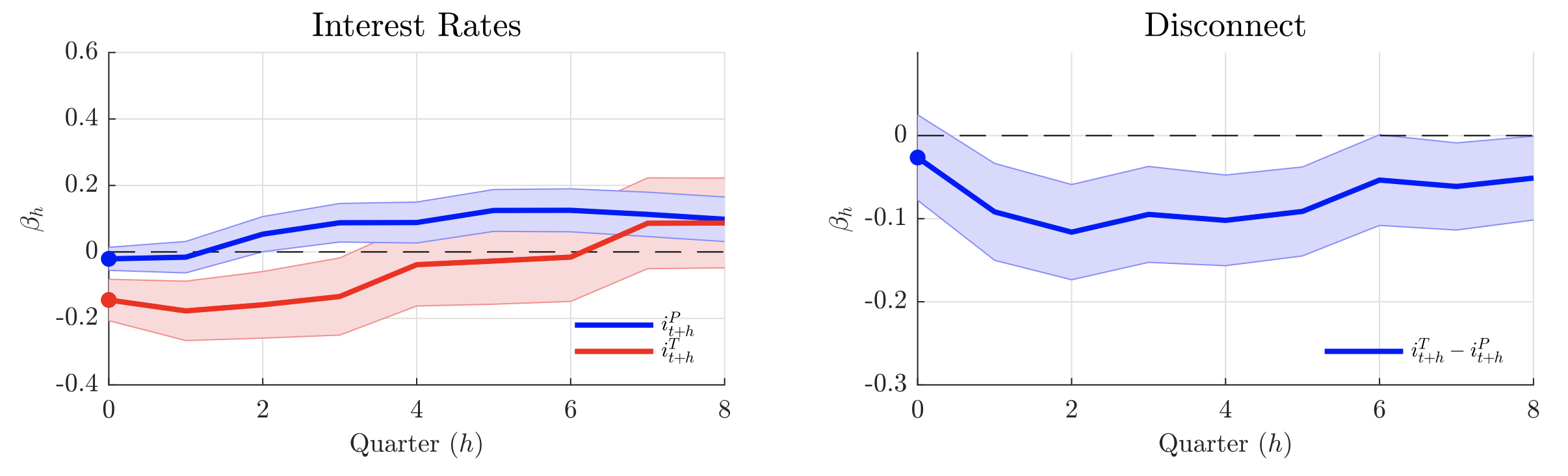

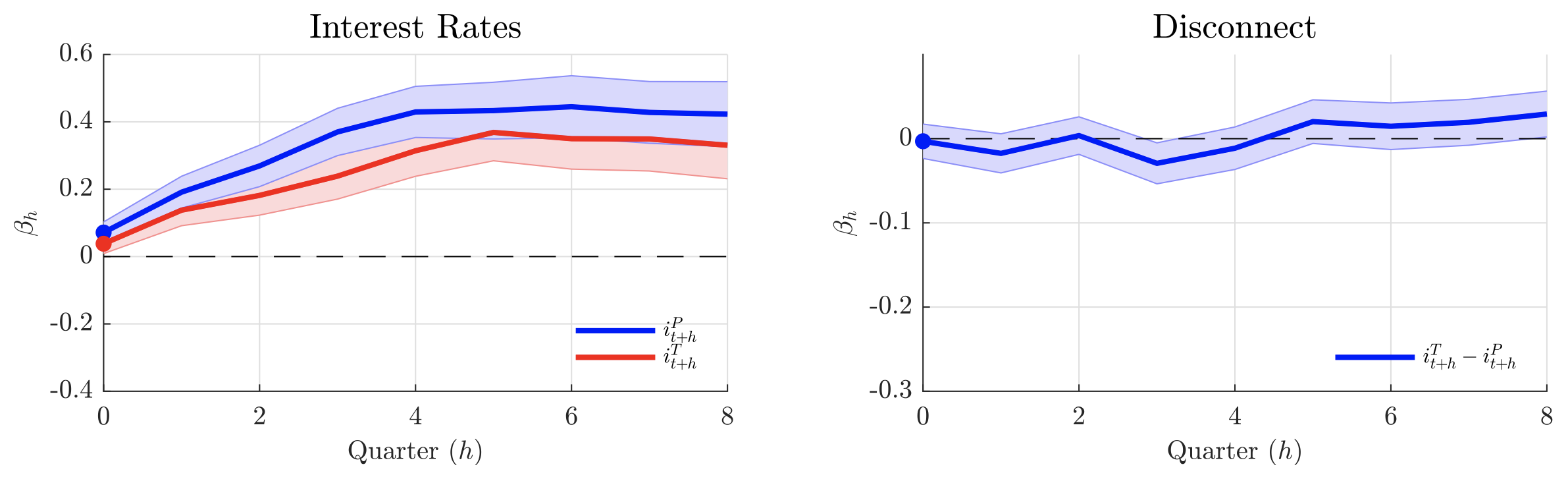

We then analyse the behaviour of short-term market rates along the business cycle. We find that short-term market rates, such as three-month government bond (treasury) rates, tend to increase when economic activity contracts in emerging economies (see Figure 1). To the contrary, we find that policy rates and short-term market rates both decline in advanced economies when economic activity decelerates (see Figure 2). Thus, local monetary policy appears counter-cyclical in emerging and advanced economies alike over the last three decades. However, emerging economies' market rates exhibit a disconnect from local policy rates, and the wedge between the two is countercyclical.

Figure 1 Cyclical behaviour of policy and short-term rates (emerging economies)

Notes: The left panel reports the correlation coefficient between the interest rate at horizon t+h and GDP growth at horizon t (while controlling for t-1 interest rate). Interest rates are either the policy rate (blue line) or the treasury rate (red line). The right panel reports the correlation coefficient between the treasury-policy differential at horizon t+h and GDP growth at horizon t (while controlling for t-1 treasury-policy differential). The shaded areas are 90% confidence intervals.

Figure 2 Cyclical behaviour of policy and short-term rates (advanced economies)

Notes: The left panel reports the correlation coefficient between the interest rate at horizon t+h and GDP growth at horizon t (while controlling for t-1 interest rate). Interest rates are either the policy rate (blue line) or the treasury rate (red line). The right panel reports the correlation coefficient between the treasury-policy differential at horizon t+h and GDP growth at horizon t (while controlling for t-1 treasury-policy differential). The shaded areas are 90% confidence intervals.

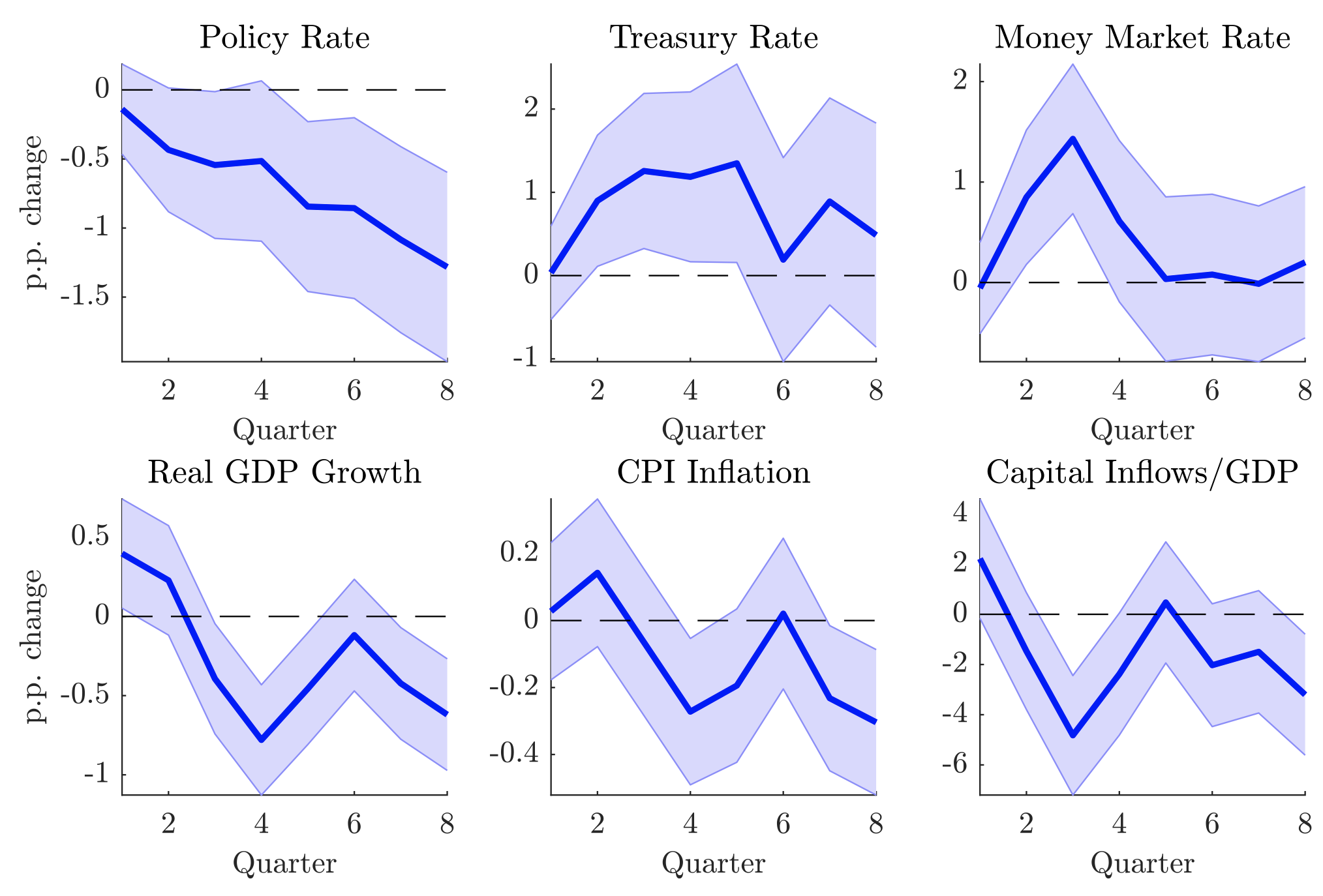

This wedge between short-term market rates and policy rates in emerging markets often emanates from their reliance on global financial markets. We examine the responses of emerging economies to identified exogenous US monetary policy shocks – a prominent cause of the global financial cycle (Miranda Agrippino and Rey 2020) – and find that the disconnect between policy rates and market rates emerges also following a US monetary policy tightening. An exogenous increase in US interest rates leads to a contraction in capital inflows, economic activity, and CPI inflation in emerging economies, as well as tighter financial conditions (as captured by the VIX). Even though central banks cut their policy rates, we observe an increase in short-term borrowing and lending market rates such as treasury, money market, and loan rates (see Figure 3). This result suggests that disruptions in global financial markets are a culprit behind the disconnect between policy rates and market rates in emerging economies.

We show that these facts are consistent with a simple model in which local banks rely not only on domestic deposits but also on the international markets for funding (as documented by Baskaya et al. 2017, di Giovanni et al. 2021, and Hahm et al. 2013). In the model, a US monetary contraction tightens global funding conditions (higher international borrowing rates), in addition to causing a decline in global demand. Short-term market rates reflect the marginal funding costs of local banks, and these are a function of both local policy rates and international borrowing rates. As a result, the pass-through of monetary policy to short-term rates is incomplete and inversely proportional to the local bank’s reliance on the global funding market.

Figure 3 Dynamic effects of a US monetary policy tightening on emerging markets

Notes: Impulse responses are obtained from panel local projections. 90% confidence intervals are shown by the shaded areas. The US policy (12-month US treasury rate) is instrumented by Gertler and Karadi (2015) shock FF4 (estimated from surprises in three-month Fed Fund Futures). Controls include four lags of the dependent variable, US 12-month treasury rate, output growth, and inflation differentials. The impulse is an impact one percentage point increase in the US policy rate.

We overall argue that changes in global risk perceptions present a serious challenge for monetary policy in emerging economies. The disconnect between policy rates and the relevant short-term market rates reveals that enacting a countercyclical monetary policy may not be enough for a central bank to provide effective stimulus to the economy. This observation revives and sheds light on the question of cyclicality of policy in emerging economies (e.g. Kaminsky et al. 2005, Vegh and Vuletin 2013). Relatedly, the disconnect between policy rates and the relevant short-term market rates represents a manifestation of incomplete monetary autonomy of emerging economies, an issue that is at the centre of recent academic and policy discussions (e.g. Rey 2013, Obstfeld 2019). We find that emerging market monetary policy follows similar countercyclical patterns to advanced economies. However, their action transmits imperfectly to markets, as market rates often turn procyclical. Understanding the deep sources of this disconnect is thus a first-order issue to understand what prevents floaters from enjoying full insulation from external shocks, and how to address it.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Baskaya, Y S, J di Giovanni, S Kalemli-Ozcan, J-L Peydro and M F Ulu (2017), “Capital flows and the international credit channel”, Journal of International Economics 108: S15–S22, 39th Annual NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics.

Calvo, G A and C M Reinhart (2002), “Fear of Floating”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(2): 379–408.

De Leo, P, G Gopinath and S Kalemli-Ozcan (2022), “Monetary Policy Cyclicality in Emerging Economies”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17748.

Gertler, M and P Karadi (2015), “Monetary Policy Surprises, Credit Costs, and Economic Activity”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7(1): 44–76.

Di Giovanni, J, S Kalemli-Ozcan, M Ulu and S Baskaya (2021), “International Spillovers and Local Credit Cycles”, The Review of Economic Studies 89(2): 733-773.

Hahm, J, H S Shin and K Shin (2013), “Noncore Bank Liabilities and Financial Vulnerability”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45(s1): 3–36.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S (2019), “U.S. Monetary Policy and International Risk Spillovers”, Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole.

Kaminsky, G L, C M Reinhart and C A Vegh (2005), “When It Rains, It Pours: Procyclical Capital Flows and Macroeconomic Policies”, In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2004.

Miranda-Agrippino, S and H Rey (2020), “U.S. Monetary Policy and the Global Financial Cycle”, The Review of Economic Studies 87(6): 2754–2776.

Obstfeld, M, J D Ostry and M S Qureshi (2019), “A Tie That Binds: Revisiting the Trilemma in Emerging Market Economies”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 101(2): 279–293.

Rey, H (2013), “Dilemma not trilemma: the global cycle and monetary policy independence”, Proceedings - Economic Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole.

Sunel, E and Y Mimir (2018), “A recipe for monetary policy in emerging market economies”, VoxEU.org, 3 April.

Vegh, C A and G Vuletin (2013), “Overcoming the Fear of Free Falling: Monetary Policy Graduation in Emerging Markets”, In D D Evanoff, C Holthausen, G G Kaufman and M Kremer (eds.), The Role of Central Banks in Financial Stability How Has It Changed?, World Scientific Publishing.