The family has served throughout history as a source of informal insurance, which can be crowded out by the market (Becker 1981). However, we know less about how informal family insurance is affected by the extension of the state, especially when individuals cannot accumulate wealth, as in communist economies. One of the main aims of Soviet communism was to remove capitalist institutions by abolishing the traditional family. However, it is an empirical question whether it managed to do so, and why it managed or failed to accomplish its goals.

The indoctrination hypothesis

Soviet communism indoctrinated its population to step out of the traditional family, which communist ideology aspired to abolish. Corneo and Grüner (2002) documented significantly stronger egalitarian preferences in Eastern than Western European countries, and this is found in Germany too (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln 2007). However, this evidence is, on first sight, inconsistent with other studies that fail to find evidence of such effects (Brosig-Koch et al. 2011). Furthermore, most of the evidence is derived from Germany, which is problematic (Mergele et al. 2020).

The informality hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is that by removing capitalist institutions, Soviet communism switched markets underground and market activities became informal (‘informality hypothesis’). This strengthened family and social networks, which acted as a form of insurance and contacts to navigate the system. However, we know very little about the effects of communism on preferences for the family as a source of informal financial and non-financial support. In a recent paper (Costa-Font and Nicińska 2023), we show that by abolishing wealth accumulation, communism created parallel informal incentives, and family networks become a source of informal insurance. Indeed, in communist societies, informal family networks were at the core (Filtzer 2014).

Exploiting evidence from four datasets – the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS), World Values Survey (WVS) and European Social Survey (ESS), supplemented with the 2006 wave of the Life in Transition Survey (LITS) – and using a quasi-experimental design, we study exposure to Soviet communism by looking at post-communist countries that vary with respect to exposure at different stages of political regime maturity, along with other European countries as controls, and different cohorts of individuals that exhibit a differential exposure over time.

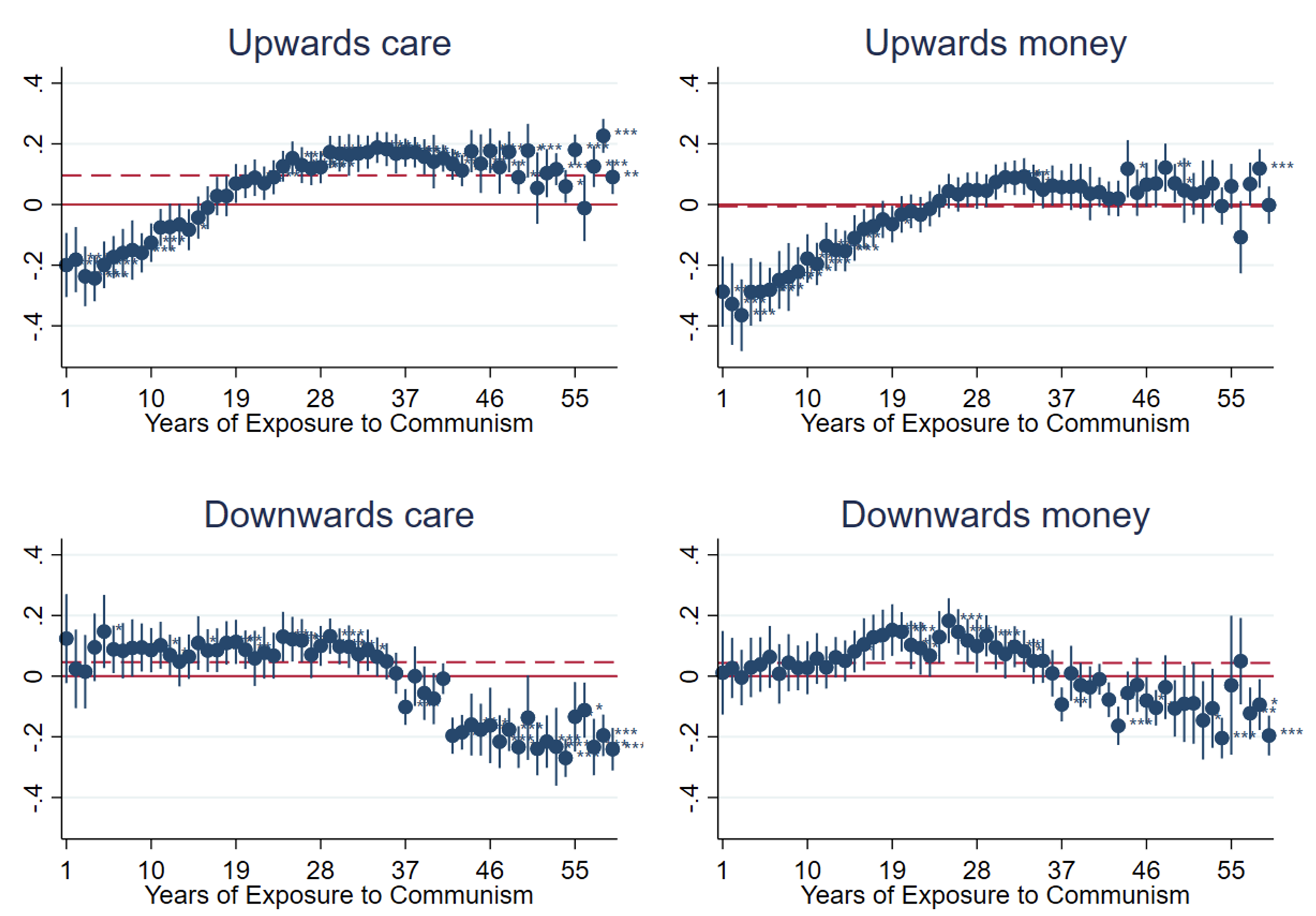

Figure 1 Effects of exposure to communism on the preference for family insurance, by length of exposure

Source: Authors’ own estimations based on GGS wave 1 (release 4.2) and 2 (release 1.3).

Notes: Point estimates with 95% confidence intervals, controlling for ability to make ends meet or scale of incomes, age (quadratic), gender, education, country, as well as time and cohort fixed effects. Dashed line shows the average effect of EC. Preference for family insurance, dichotomous: upwards care – “children should take responsibility for caring for their parents when parents are in need”, downwards care – “grandparents should look after their grandchildren if the parents of these grandchildren are unable to do so”, upwards (downwards) money – “children (parents) ought to provide financial help for their parents (adult children) when their parents (the children) are having financial difficulties”. Robust standard errors clustered by year of birth and country. Statistical significance: *** – p<0.01, ** – p<0.05, * – p<0.1.}

We show that individuals exposed to communism are more likely than individuals unexposed to communism to report that members of a family should support each other, especially when personal care for older parents is needed (9.6 percentage points more likely) and even support for children (both financial and non-financial) is needed (4.3 percentage points more likely). In other words, in contrast to predictions of the indoctrination hypothesis, we find evidence of the strengthening of the preference for family support, consistent with the informality hypothesis. Figure 1 shows that the effects of exposure to communism on intergenerational support for both older and younger generations are positive. In the case of preferences for family financial transfers toward older individuals, we find an insignificant negative exposure effect, which could be explained by the extensive and generous retirement schemes in formerly communist countries.

Trust as a mechanism

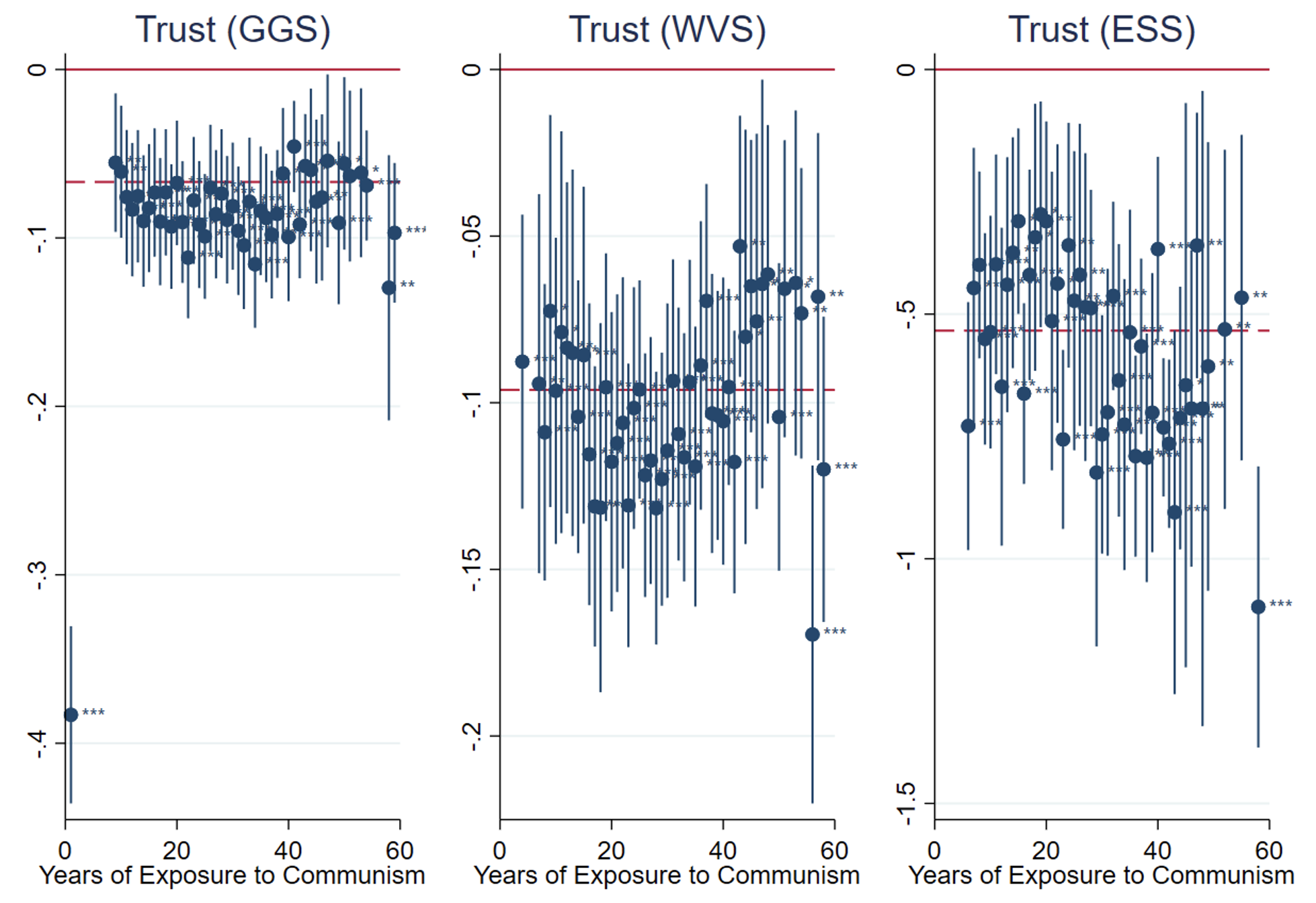

One mechanism of the preferences for family support comes from the erosion of generalised trust strengthening trust in the family, consistent with Fukuyama’s (1996) ‘paradox of family values’, whereby low-trust societies are characterised by large families exhibiting strong internal ties. Consistent with this, we confirm that the probability of agreeing with the statement that “most people can be trusted” declined on average by 11% (19%) due to exposure to communism, as reported in Figure 2.

Depressed civic participation

Soviet communism depressed civic participation and support for democratic values. If public institutions are perceived as corrupt and people withdraw from expressing their voice in public due to little reliance on democratic institutions, it is reasonable to expect a higher preference for placing the responsibility for individuals in need of support on informal family networks rather than the state.

Figure 2 Effects of the exposure to communism on generalised trust and confidence in public institutions

Source: Authors’ own estimations based on GGS wave 1 (release 4.2) and 2 (release 1.3), WVS waves 2-6 (release 2015_04_18), ESS waves 1-8.

Notes: Point estimates with 95% confidence intervals, controlling for ability to make ends meet or scale of incomes, age (quadratic), gender, education, country, as well as time and cohort fixed effects. Dashed line shows the average effect of EC. Trust – generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people? Robust standard errors clustered by year of birth and country. Statistical significance: *** – p<0.01, ** – p<0.05, * – p<0.1.

Heterogeneity

We find that the effects on preference for family insurance are driven by women. Furthermore, the analysis by various country groups reveals substantial heterogeneity across countries exposed to Soviet communism. We show that the effects of exposure are most pronounced in the formerly Habsburg and Prussian lands compared to Russia, pointing to the role of religion and related cultural values (Nikolova and Djankov 2018).

The role of family changes with political regimes

By weakening trust and abolishing the accumulation of wealth, Soviet communism strengthened preferences for family support. That is, the Soviet communist regime increased not only preferences for social insurance (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln 2007) but the demand for family support (insurance), suggesting that family structures are very much endogenous to political regimes.

References

Aghion, P, Y Algan, P Cahuc and A Shleifer (2010), “Regulation and distrust”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(3): 1015–1049.

Alesina, A and N Fuchs-Schündeln (2007), “Goodbye Lenin (or not?): The effect of communism on people’s preferences”, American Economic Review 97(4): 1507–1528.

Becker, G S (1981), “Altruism in the family and selfishness in the market place”, Economica 48(189): 1–15.

Brosig-Koch, J, C Helbach, A Ockenfels and J Weimann (2011), “Still different after all these years: Solidarity behavior in East and West Germany”, Journal of Public Economics 95(11-12): 1373–1376.

Corneo, G and H P Grüner (2002), “Individual preferences for political redistribution”, Journal of Public Economics 83(1): 83–107.

Costa-Font, J and A Nicińska (2020), “Comrades in the Family? Soviet Communism and Informal Family Insurance”, Kyklos, forthcoming.

Filtzer, D (2014), “Privilege and inequality in communist society”, in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism, Oxford University Press.

Fukuyama, F (1996), Trust: Human nature and the reconstitution of social order, Simon and Schuster.

Mergele, L, L Woessmann and S O Becker (2020), “German division and reunification and the ‘effects’ of communism”, VoxEU.org, 5 April.

Nikolova, E and S Djankov (2018), “Communism, religion, and unhappiness”, VoxEU.org, 26 April.