There has been an ongoing discussion about why trade growth has not recovered since the Great Trade Collapse, and why the trade to GDP elasticity has slowed down as much as it has. Previous VoxEU columns have highlighted the relative importance of cyclical and structural/supply side factors. For example, during the 2011-13 period, the importance of cyclical factors was strong – weak aggregate demand in advanced economies, linked in particular to the Eurozone crisis of 2011-13, was a main contributor to the slowdown (Aslam et al. 2017). This phenomenon was amplified by the fact that the share of the Eurozone in world trade is larger than in GDP, thus depressing the former more than the latter. Other researchers have emphasised the importance of structural factors, whereby the slower pace of global value chain expansion would have significantly affected the expansion of trade. Constantinescu et al. (2015) make the point that the slowdown in the growth of global value chain related trade (as measured by trade in intermediates) has been a significant contributor to the slowdown. Other major factors, such as changes in the composition of GDP and trade, have also been mentioned in the literature (Haugh et al. 2016).

From the outset, Bussiere and co-authors have adopted an original approach to incorporating the changing patterns of trade into demand-based analysis (Bussiere et al. 2012). Rather than using a standard import demand model, whose predictive value has declined considerably since the global trade collapse, the authors construct an import-intensity adjusted measure of aggregate demand, essentially weighting each component of expenditure by its import intensity, computed from OECD input-output tables. This hybrid form of income based models that include demand has showed promising results, which were then the basis for the analysis carried out by the IMF in its WEO chapter in 2016. Still, both analyses relied on input-output data that did not go beyond 2011.

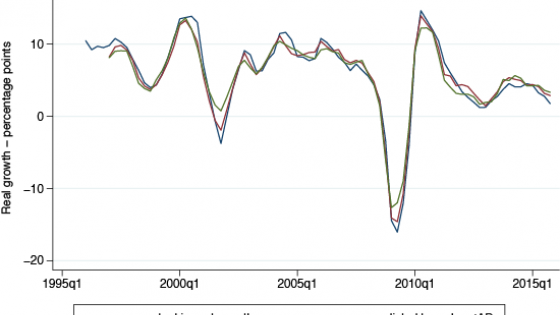

Using 2016 release of the World Input-Output Tables, we have been able to recalculate import intensity aggregate demand, with fresh weights for expenditure components (consumption, investment, etc.) of the 38 countries that account for 80% of world trade. As shown in Figure 1, the import content of total investment, although levelling off, is now 37% of its value for the average economy, the highest of all aggregate demand components; the import content of exports is, by country, more than 30% on average; and that of consumption has grown recently, although it is still not as high as the other two components of demand.

Figure 1 Import content for 40 countries, 1995-2014

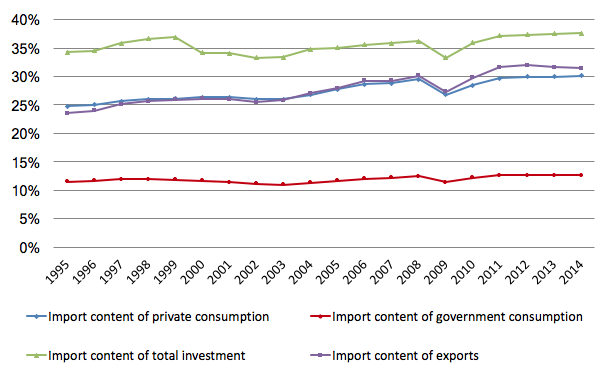

When looking at the evolution of investment in particular, one can see that, in advanced countries, it is the only component of aggregate demand whose share in GDP has not recovered its pre-2009 crisis level (Figure 2). Gross fixed investment in emerging and developing countries has been more resilient in the immediate aftermath of the Global Crisis. It continued to increase strongly until 2012, and then stagnated in 2013-2014, before falling as a share of GDP (particularly corporate investment). This may reflect China rebalancing its economy away from investment and toward consumption, and the slowdown in investment among commodity exporters. Exports, with their high import contents in all the major traders, have also stagnated. It is therefore not surprising that trade growth has been slow, as the most trade-intensive elements of economic activities have been growing the slowest globally.

Figure 2 Share of investment in GDP, 1995-2016

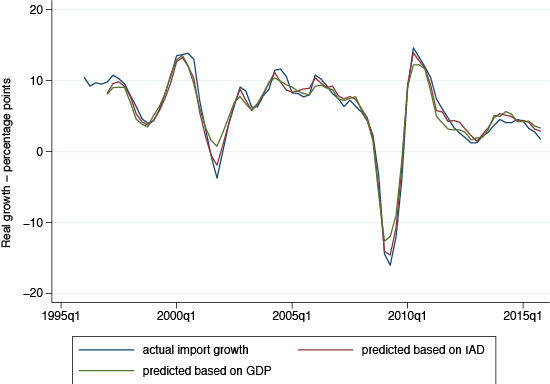

We find a lower and less volatile long-term elasticity of imports to demand (1.5 instead of 2 for GDP) when we used this concept of import-adjusted demand. Further, the integration of import-adjusted demand into the standard global import equation helps predict 76% to 86% of the changes in values of global imports, a better performance than that achieved using GDP. The use of import-adjusted demand also enabled us to measure the relative importance of each component of demand, according to their trade intensity. The model is able to account for over 90% of the recent trade slowdown (2012-2015), with import-adjusted demand alone explaining 80% of it. As mentioned above, the composition of demand is the primary explanation of the trade slowdown because the most trade-intensive components were the ones slowing down the most (such as investment). The slowdown in global value chains explains more than half of the remaining share of the global trade slowdown that isn’t explained by demand factors (around 10%). Protectionism does not come up as statistically significant.

Figure 3 below shows that when we forecast global imports with import-adjusted demand as the proxy of economic activity ex-post, we find that import-adjusted demand (red line) is a much better fit to reality (blue line) than GDP (green line).

Figure 3 Forecast of global imports, 1995-2015

How does this help analysis? First, it improves our take on global forecasts of trade. Second, in the evolution of global trade, we are able to breakdown trade growth by demand component, and explain whether trade slows down (or accelerates) as a result of a specific demand component or changes in its trade intensity. We are able to decompose for each country and hence improve our overall understanding of the underlying trade dynamics.

For the first time, these methodological developments have been integrated in the making of WTO's trade forecasts as a complement and possible alternative to ordinary GDP-based modelling, given the current tendency of GDP-based models to over-predict global trade flows.

References

Aslam, A, E Boz, E Cerutti, M Poplawski-Ribeiro, P Topalova (2017), “Global trade: Drivers behind the slowdown”, Voxeu.org,13 February.

Auboin, M and F Borino (2017), “The falling elasticity of global trade to economic activity: Testing the demand channel”, WTO Working Paper ERSD-2017-09.

Boz. E, M Bussière and C Marsilli (2014), “Recent slowdown in global trade: Cyclical or structural”, VoxEU.org, 12 November.

Bussière, M, F Ghironi and G Sestieri (2012), “Estimating trade elasticities: Demand composition and the trade collapse of 2008–09”, VoxEU.org, 14 February.

Bussière, M, G Callegari, F Ghironi, G Sestieri and N Yamano (2013), “Estimating trade elasticities: Demand composition and the trade collapse of 2008–09”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5(3): 118–51.

Constantinescu, M, and Ruta (2015), “Explaining the global trade slowdown”, VoxEU.org, 18 January.

Haugh, D, A Kopoin, E Rusticelli, D Turner and R Dutu (2016), "Cardiac Arrest or Dizzy Spell: Why is World Trade So Weak and What can Policy Do About It?", OECD Economic Policy Papers, No.18, OECD Publishing, Paris. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlr2h45q532-en

Hoekman, B (ed) (2015) The global trade slowdown: A new normal?, VoxEU E-book, CEPR, London.